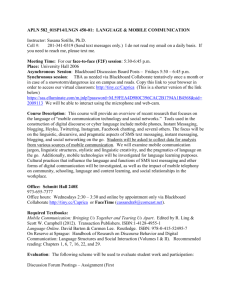

Best Practices Distance Education

advertisement