Comments Opposing Serenity Springs`s CBW Permit Application

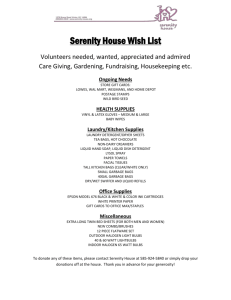

advertisement