ACCT341, Ch14 - Personal Pages Index

advertisement

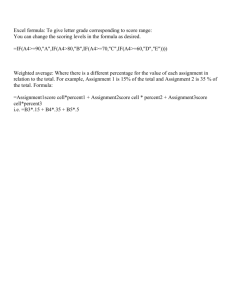

ACCT341, Chapter 12 Read the first few pages of Ch. 12 and answer the following questions: 1. Who should internal auditors report to? Why? 2. What is the primary concern of internal auditors? 3. What is the chief purpose of an external audit? 4. T or F: If internal controls are strong, auditors can rely on the controls and thus need to do less substantive testing. 5. T or F: Auditors’ objectives in reviewing IS controls include: (a) to evaluate the risk that control weaknesses will compromise the integrity of the financial reports (numbers are wrong); and (b) to find control weaknesses and recommend fixes. 6. What is the ideal background for an IS auditor? 7. T or F: People skills are arguably the most important skill required by auditors. 8. How does one become a CISA? 9. Give two examples of how GAS can assist auditors. 10. Suppose you’re auditing loans receivable at a bank. You need to pick a random sample of loans, including loans over a certain dollar amount, as well as loans with certain kinds of collateral (e.g. airplane loans). Which one of the following commands in a GAS package would be most useful to obtain generate this sample: stratify, extract, or join? 11. How does auditing around the computer differ from auditing through (or with) the computer? 12. T or F: In a highly complex computerized information system, it is nearly impossible to audit around the computer. 13. List five approaches to through-the-computer auditing. 14. (A) Identify three approaches to test that computer programs are properly processing data. (B) Which approach would have the greatest danger of contaminating real data with fictitious data? The least danger? (C) Which approach do you think would be the most expensive to use? Why? 15. What are two ways to minimize the chance that a clever programmer might substitute a legitimate program for a dishonest one when the auditors ask for the program in order to test it? 16. How can an auditor test the systems software to ensure controls are working properly? 17. Of the password parameter examples listed in Fig. 12-7, if you had to pick three parameters in combination, which three do you think would be the most effective at preventing unauthorized access? 18. (A) T or F: Exception reporting is a form of continuous auditing. (B) At a bank or credit union, the computer system will automatically generate exception reports that print out all changes and overrides made (e.g. changes to an interest rate on a borrower’s loan or override of an automatic late fee). Also, the computer system will maintain a log of who was logged on at what times during the day. If you were an auditor at a bank, what would you look for in these exception reports? 19. Briefly describe how each of the following work: (A) embedded audit module or audit hook, (B) transaction tagging, and (C) snapshot technique. 20. Which section of SOX is keeping management and the auditors of public companies the busiest? Why is it so time consuming? 21. Auditors must be aware of the tools used for detecting errors. A simple spreadsheet error can be costly. For example, an accountant in a construction company inserted $254,000 of costs into a cell of a spreadsheet, not noticing that the inserted cell was outside the range to be summed for total costs. This mistake caused the company to underbid a job by $254,000. A similar event happened in a construction bid at a nearby institution in Walla Walla. In auditing an Excel spreadsheet, there are ways to look for spreadsheet errors other than just visual inspection. (A) Obtain the P21 Excel spreadsheet by clicking on the link on the course webpage entitled P21. Use the Formula Auditing tools described at the end of this document to identify formula errors in this spreadsheet. Find at least one error and describe the error and how you found it. (B) Use the Data Validation feature described at the end of this document and then try entering a number outside the range criteria. Did it work? You do not need to submit this spreadsheet as part of your assignment. 22. Refer to the article below entitled Turn Excel Into a Financial Statement Sleuth and answer the following question: (A) According to Benford’s Law, what percent of the time should a number contain the first digit of 1? The digit of 9? (B) How could auditors use Benford’s Law in their work? 23. Obtain the P23 Excel spreadsheet by clicking on the link on the course webpage entitled P23. Using the Excel spreadsheet tools available (or your own methods which are probably better), debug the spreadsheet and compute the correct total pay for the pay period. Submit a copy of your spreadsheet as part of this assignment. (Hint: grand total should be close to $19,700). Assume the following policies: (A) A minimum wage of $7.50 must be paid to all employees. If a wage rate less than the minimum is recorded, it must be changed to the minimum. Any negative numbers should be changed to be positive numbers. (B) The highest wage that can be paid is $40 per hour. If a wage of more than the maximum is recorded, it must be changed to the maximum. (C) Timecards allow only 15-minute increments, i.e. an employee can’t report time at a fraction other than .25, .50, or .75 of an hour. If time is recorded at an incorrect fraction, it must be rounded to the nearest legitimate increment. (D) Overtime is paid at a time-and-a-half or 1.5 times normal wage only for hours worked in excess of 40 per week. The total hours reported (regular and overtime) is the correct total hours worked. (E) Given budget constraints, under no circumstances will an employee be paid for working more than 50 hours per week. (F) All employees must be paid for no less than half-time or 20 hours per week. Sleuthing With Excel Newer Versions of Excel Formula Auditing: On the top menu of Excel, go to Formulas, see Formula Auditing section. Perform the error checking function to find and correct the formula errors. You can also display Precedent and Dependent arrows to show the formula pattern among the cells. Finally, you can show formulas, which often immediately makes and formula visibly apparent. Data Validation: On the top menu of Excel, go to Data and then under the Data Tools section, go to Data Validation. Use the validation tool to verify data as it is being entered. For example, highlight the payrate range and set the data validation decimal feature between $7.50 and $40.00. From this point on, any data entered in the payrate range that does not fall between these two values will be flagged. Older Versions of Excel Formula Auditing: On the top menu of Excel, go to FormulaTools, Formula Auditing and Show Formula Auditing Toolbar. Perform the error checking function (first icon on toolbar) and find and correct the formula errors. You can also display Precedent and Dependent arrows to show the formula pattern among the cells. Data Validation: On the top menu of Excel, go to Data and then Validation. Use the validation tool to verify data as it is being entered. For example, highlight the payrate range and set the data validation decimal feature between $7.50 and $40.00. From this point on, any data entered in the payrate range that does not fall between these two values will be flagged. Home · Online Publications · Journal of Accountancy · Online Issues · August 2003 ·Turn Excel Into a Financial Sleuth TECHNOLOGY WORKSHOP An easy-to-use digital analysis tool can red-flag irregularities. Turn Excel Into a Financial Sleuth BY ANNA M. ROSE AND JACOB M. ROSE ne of our small business clients—we’ll call him Bob—recently expanded his one-store, family-run retail operation into a four-store chain. As many small business owners have to do, Bob had to relinquish some hands-on control when his business grew. He had to hire new employees for each store, and he worried about the possibility of bookkeeping errors and, even worse, fraud. Adding to his concern was his need to install modern electronic technologies to link the four locations. Instead of trusted family members responsible for a single cash register, Bob now had many operators at point-of-sale (POS) terminals and purchasing agents in different locations handling electronic disbursements to hundreds of vendors—an ideal environment for irregularities. The POS system produced spreadsheets that tracked daily sales, returns and disbursement data—all of which could be aggregated by employee. While the POS tool could generate custom financial reports useful for decision making, it was unable to spot clues about irregularities. EXCEL TO THE RESCUE That’s where we came into the picture as consultants. We suggested running a digital-analysis process based on Benford’s Law, which can detect irregularities in large data sets. (For more on Benford’s Law, see “I’ve Got Your Number,” JofA, May99, page 79.) We told Bob he didn’t need to buy any special software to use the process, and that with a few modifications, Excel could do the job. As it turned out, the process paid off handsomely. Within a few weeks it revealed irregularities in a sample of cash disbursements to vendors, and after further investigation, Bob concluded that one of his new employees probably was committing fraud. Exhibit 1 This article will explain how you can turn Excel into a financial detective by using Benford’s Law and customize Excel programs to perform sophisticated digital analyses that can uncover errors and fraud. Benford’s Law predicts Exhibit 2 the occurrence of digits in large sets of numbers. Simply put, it states that we can expect some digits to occur more often than others. For example, the numeral 1 should occur as the first digit in any multiple-digit number about 31% of the time, while 9 should occur as the first digit only 5% of the time. We also can apply the law to determine the expected occurrence of the second digit of a number, the first two digits of a number and other combinations. How can such predictions red-flag an irregularity? When someone creates false transactions or commits a data-entry error, the resulting numbers often deviate from the law’s expectations. This is true when someone creates random numbers or intentionally keeps certain transactions below required authorization levels. When Excel spots the deviation, it raises a red flag. Considerable statistical research supports the effectiveness of Benford’s Law, making it a valuable tool for CPAs. The technique isn’t guaranteed to detect fraud in all situations but is useful in analyzing the credibility of accounting records. A NOTE OF CAUTION Benford’s Law is not effective for all financial data. If the data set is small, the law becomes less accurate because there are not enough items in the sample and so the rules of randomness don’t apply—or at least apply with less predictability. Also, if the data include built-in minimums and maximums, they also might not conform well to the law’s predictions. For example, consider a petty-cash fund where all disbursements are between a $10 minimum and a $20 maximum. All first digits would be either 1 or 2, and the expected distribution of first digits would not apply. Likewise, when a company’s major product sells for, say, $9.95, most sales totals will be a multiple of 995, again offsetting the value of the process. Finally, when a data set consists of assigned numbers, such as a series of internally generated invoice numbers, the data will not follow a Benford distribution. For a demonstration of how the fraud-detection spreadsheet works, you can download an Excel file that contains sample data and the Visual Basic for Applications (VBA) code that automates the calculation of the data from http://www.aicpa.org/download/pubs/jofa/2003_08/Fraud_Buster.xls. For those who want to create their own VBA code or alter the downloaded program to perform other digital analysis tests, download an instruction manual “How to Create the Fraud Buster Application” from http://www.aicpa.org/download/pubs/jofa/2003_08/How_to_create_Fraud_Bu ster_Application.doc. Once you’ve downloaded the file, you can perform tests on any spreadsheet data. Further, you can easily import database data into Excel and then analyze them. You even can download live Internet data for that purpose. To start the test, open the Enter Data worksheet—using either the sample data or after importing your own data—and press the Run Fraud Buster button (see exhibit 1, above). Guided by the VBA code, Excel will analyze the data using three tests: firstdigit, second-digit and first-two-digits. Once it completes its analysis, the program will open the second worksheet, First-Digit Test (see exhibit 2, above), and display the results: a table with the Benford predictions for firstdigit frequencies, the actual sample frequencies, the differences between the sample and Benford frequencies and a bar chart that graphically compares the financial data with the law’s predictions. It’s immediately obvious from the bar graph that the digits in our disbursement data do not conform to Benford predicted rates. The digits 5, 6 and 7 appear much more frequently than expected, while the digit 1 is noticeably absent. This type of result indicates that it may be necessary to investigate further. The first-digit test analyzes the reasonableness of the data, which can be very valuable to internal and external auditors. Additional tests of the digits can help to isolate the cause of deviations from Benford’s expectations. To see the results of the second-digit test, click on the SecondDigit Test worksheet tab (see exhibit 3, at right). Notice that in this analysis, the digit zero is included in the table of expected digits; as a result, the Benford formula for the second-digit test is more complex. An Exhibit 3 analysis of the bar chart shows the sample data deviate from Benford’s predictions for seconddigit frequencies— further evidence of irregularity. Now click on the First-Two-Digits Test worksheet (see exhibit 4, below). The following formula calculates the Benford predicted rates for the first two digits: Log10 (1+1/twodigits). With these four worksheets, you are armed and ready. Import the data you wish to analyze into the Enter Data worksheet and press the Run Fraud Buster button. The second-digit test confirms the existence of deviations from expectations. The digits 6 and 7 appear far more often than expected. Finally, the analysis indicates that 56 and 67 appear as the first two digits far more often than expected. It may be possible an employee is creating fictitious disbursements, and he or she has a tendency to overuse 5, 6 and 7 when creating false disbursement data. Alternatively, there may be a $1,000 limit on unauthorized disbursements to vendors, and an employee is creating false disbursements that are comfortably below the cutoff. Exhibit 4 The real-life Bob investigated a sample of the disbursements that started with the digits 56 and 67 and soon discovered disbursements to an unfamiliar vendor. Additional sleuthing revealed the vendor did not exist, and the employee actually was sending payments to a personal account. Digital analysis using Benford’s Law and the fraud-buster spreadsheet swiftly exposed the crime and its source. Bob spent only minutes learning to use the spreadsheet. It now is a part of his personal arsenal against fraud and employee errors. ANNA M. ROSE, CPA, PhD, and JACOB M. ROSE, PhD, are assistant professors at Montana State University at Bozeman and principals of Progression Consulting Group. ©2003 AICPA