Application 2016 NEH Summer Seminar for Faculty

2016 NEH Summer

Seminar

Endangered Species Across the Years:

Changing Philosophies and Policies

June 27-July 21, 2016

SUNY Potsdam

Seminar Leader:

Edward P. Weber

U. G. Dubach Professor of Political Science

School of Public Policy

Oregon State University

Applications Due by March 4

th

to

Geoffrey Clark

Department of History

321 Satterlee Hall

SUNY Potsdam

44 Pierrepont Ave.

Potsdam, NY 13676 clarkgw@potsdam.edu

1

Endangered Species Across the Years:

Changing Philosophies and Policies

Edward P. Weber

U. G. Dubach Professor of Political Science

School of Public Policy

Oregon State University

The decline and loss of species around the world is not a trivial matter for either humans or nature; when species decline and disappear there are heavy, sometimes irreversible ecological costs and significant costs to humans. The question is, how did we get to such a state of affairs? And what, if anything, have we done, and are we doing, to protect species from harm and aid in their recovery if they are in a dangerous state of decline? This seminar explores these questions by taking an interdisciplinary approach that examines how human philosophies, social movements, and public policies have approached the relationship between humans and nature, and particularly species, over the past 200 years in the U.S. Attention is also given to species loss around the globe.

The key theme is one of change: the relationship between humans and nature in the

U.S. has transformed significantly from an almost entirely exploitative “humans against nature” perspective that treated nature as a hindrance to progress and as a store of commodities for human benefit to more of a “humans with nature” and

“preserve nature for its own sake” outlook that accords nature and species much higher value in the larger scheme of societal values. To establish and elucidate the different approaches to nature and species, the changes between 1800 and the present, and the record of species’ decline, the seminar relies on readings from influential thinkers and policymakers, legal documents, court cases, and congressional testimony, along with the standard secondary literature associated with the various topics.

The course is divided into eight sessions, which will be held Tuesdays and

Thursdays over a four-week period in June and July 2016.

Session 1/Tuesday, June 28: Exploiting and Civilizing Wilderness

After an opening lecture on the scale and scope of the problems facing species in the

US and around the globe, and discussion over why there are concerns, Session 1 will turn to the exploration and development of the philosophies guiding the early days

2

of the U.S republic, which exhibits a classic case of humans against nature in a fight for survival and the advancement of civilization into previously wild, largely unsettled lands. Materials here are derived from John Locke’s labor theory of property, the utilitarianism of JS Mill and Jeremy Bentham, de Tocqueville’s links between wild nature and the strength of American democracy, and Christian perspectives, among others, on the need to tame and transform the wilderness for human purposes. This “dark” take on nature and wildness as an “opponent” of human civilization/progress is critical to understanding the early years of flat out development, decimation of species, and subjugation of nature for human needs.

Bible, The Book of Genesis.

De Tocqueville, Alexis. 1835. Democracy in America. Excerpt from Chapter XVII

“Principal Causes Maintaining The Democratic Republic – Part I.”

Locke, John. 1689. Two Treatises of Government. Excerpt from Chapter 5, “Of

Property.”

Milburn, William Henry. 1859. Rifle, Axe and Saddle-bags, and Other Lectures.

Excerpt, pp. 2 – 5. Derby & Jackson Publishers.

Mill, J.S. 1863. Utilitarianism. Excerpt from Chapter 2, “What Utilitarianism Is.”

Riesner, Marc. 1986. Excerpts from Cadillac Desert: The American West and Its

Disappearing Water. Viking Press.

The Morning Post. 1899. “How Bison Perished,” (December 27). Raleigh, NC.

Session 2/Thursday, June 30: Changing Values Gather Momentum

Session 2 gives attention to the nascent movement of American society in the 19 th century, particularly in its closing decades, and early 20 th century toward new ideas about the proper relationship of humans to nature. It starts with Ralph Waldo

Emerson’s poem Nature (1836), and reflects on the work of Thoreau, John Muir

(founder of Sierra Club), plus others who express a reverence for nature, while extolling its essentiality to the human experience. This is also a spiritual take on the value of nature that seeks to convince people to preserve nature, rather than develop it. We will also cover the Progressive Era conservationism of T.R. Roosevelt and Gifford Pinchot, first leader of the USFS. The new federal agencies and policies designed to develop natural resources more sustainably (at least in theory) are important here as well.

Emerson, Ralph Waldo. 1836. “Nature” (excerpt).

The Lacey Act of 1900. (18 USC 42-43 16 USC 3371-3378)

Muir, John. 1908. “The Hetch Hetchy Valley,” Sierra Club Bulletin (January) Vol VI,

No. 4.

Nash, Roderick. 1967. Excerpts from Wilderness and the American Mind. New Haven,

CT: Yale University Press.

Roosevelt, T. R. 1908. ““Conservation as a National Duty,” a speech to the Conference on the Conservation of Natural Resources (May 13), Washington, D.C.

Forest and Stream. 1882. “Spare the Trees [editorial].”

3

Weber, Edward P. 2000. “A New Vanguard for the Environment: Grass-Roots

Ecosystem Management as a New Environmental Movement,” Society and

Natural Resources 13 (3): 237-259. [Read only sections on Preservation and

Conservation Movements]

Session 3/Tuesday, July 5: Species Protection in the Age of

Industrialization & Suburbanization (1916-1965)

This section shows the impacts of industrialization and urbanization on species, especially biodiversity, while also presenting the struggles within the National Park

Service over balancing ecological concerns with development/recreation interests, and the passage of key legislation such as the 1934 Duck Stamp Act. Other critical topics are Aldo Leopold’s highly influential “land ethic,” reported out in a collection of essays in The Sand County Almanac in 1949, and the effects of urbanization and suburbanization on biodiversity. Rachel Carson’s explosive, bestselling book in

1962, Silent Spring, takes direct aim at the major, sometimes life threatening problems chemicals and other industrial pollutants pose to animals, plants, and ecosystems. During the same period, other environmental advocates, including

Howard Zahniser and Aldo Leopold, both founders of the Wilderness Society, and

David Brower of the Sierra Club, fought for the preservation of wild and scenic rivers and their canyons by mounting national campaigns to stop big dam projects.

Their success was codified with the passage of the 1964 Wilderness Act--a watershed event because it created a national system of permanent protection for millions of acres of wildlands and the species contained therein.

Carson, Rachel. 1962. Silent Spring. [excerpts]

Duck Stamp Act of 1934. (aka The Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamp

Act)

Duncan, Dayton. 2009. “George Melendez Wright and the National Park Idea,” The

George Wright Forum 26 (1): 4 – 13.

Hardman, Sam. 2011. “ How does Urbanization Affect Biodiversity?” ( November 6) http://ecologicablog.wordpress.com/2011/11/06/how-does-urbanizationaffect-biodiversity-part-one/

Leopold, Aldo. 1947. “The Ecological Conscience,” a speech to the Conservation

Meeting in Minneapolis, Minnesota on June 11. [This excerpt taken from The

Missouri Conservationist 9 (6) (June 6, 1948): 2]

The Living Wilderness. 1956-57. “The Need for Wilderness Areas,” 59 (Winter-

Spring), pp. 58-63.

Wilderness Act of 1964. [a 3-page excerpt]

Further Readings:

Leopold, Aldo. 1949. A Sand County Almanac. New York: Oxford University Press.

Meine, Curt. 1988. Aldo Leopold: His Life and Work. Madison, WI: University of

Wisconsin Press.

Sellars, Richard West. 1997. Preserving Nature in the National Parks: A History. New

Haven: Yale University Press.

4

Werner , Marten Winter. 2014. “A global analysis of the impacts of urbanization on bird and plant diversity reveals key anthropogenic drivers,” Royal Society

Proceedings B. http://rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/281/1780/20133330

Session 4/Thursday, July 7:

A Turning Point in the Quest to Protect Endangered Species (1965–1981)

The activities and legislative successes of Carson, Zahniser, Brower and others were the leading edge of a new environmental movement commonly known as the contemporary environmental movement, which was markedly different than the dominant conservation movement. Movement leaders, such as Paul Erhlich, a scientist, and David Brower of the Sierra Club, argued that nature and humankind were in inexorable conflict; there were too many people consuming too many resources, producing too much pollution, and threatening the viability of too many species. The policy focus was therefore broader than before, focusing on the degradation of natural resources, pollution control and the negative effects of pollution on human health, and an emphasis on non-material “quality of life” as the primary indicator of progress.

The result was a national, broadly bipartisan awakening that produced an explosion of federal legislation, including critical policies that sought to rebalance the equation between humans and species more in favor in species, including the 1973 ESA, the wetlands section (404) of the 1972 Clean Water Act, the new, more environmentally friendly 1976 Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA) for the U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM), and the Alaska National Lands Act of 1980. The first major court test for the ESA—Tennessee Valley Authority v. Hill (1978)—is also reviewed as is a series of initiatives that changed the legislative and regulatory rules in an attempt to protect and preserve endangered salmon and steelhead fisheries within the Columbia River Basin in the Pacific Northwest.

(excerpts from) Goble, Dale, J. Michael Scott, and Frank W. Davis. 2005. The

Endangered Species Act at Thirty: Renewing the Conservation Promise, Volume

I. Washington, D.C.: Island Press.

Tennessee Valley Authority v. Hill (437 U.S. 153), 1978 [excerpt]

Weber, Edward P. 2000. “A New Vanguard for the Environment: Grass-Roots

Ecosystem Management as a New Environmental Movement,” Society and

Natural Resources 13 (3): 237-259. [Read section on Contemporary

Movement]

Weber, Edward P. (forthcoming), “The [1973] Clean Water Act, Riparian Zones, and

Wetlands.”

Wilkinson, Charles. 1992. “The River was Crouded with Salmon,” in C. Wilkinson,

Beyond the Next Meridian. Washington, D.C.: Island Press: 175 – 218.

Further Readings:

5

Doremus, Holly. 2005. “The Story of TVA v. Hill: A Narrow Escape for a Broad New

Law,” in R. J. Lazerus and O. Houck, Eds., Environmental Law Stories. New

York: Foundation Press.

National Research Council. 2001. Compensating for Wetlands Losses under the Clean

Water Act. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press.

Session 5/Tuesday, July 12: Backlash, Battles, and Changing Methods for Protecting Species (1981–present)

Session 5 examines the political backlash to the implementation of the many new environmental protection laws, while also developing an understanding of developments that extend the reach of the ESA onto private property. Reagan era reforms and the takings (5 th Amendment) and property rights battles are covered, as are wolf recovery efforts around Yellowstone National Park, and the emergence of a new environmental movement grounded in cooperative conservation and sustainability.

Extending the Definition of Harm to Include Habitat: The Case of Babbitt v. Sweet

Home (1995, 515 U.S. 687) [excerpt of Supreme Court case]

Fifth Amendment, U.S. Constitution.

Kleckner, Dean. 1993. American Farm Bureau leader, statement at the Annual

Meeting Of The American Farm Bureau Federation.” (Taken from the

Congressional Record, 104 th Congress.) (on property, ESA and wolves)

Reagan Administration and ESA Reform in 1982 (10A and 10J rules)

Kostyack, John. 1999. “The Need for HCP Reform,” Endangered Species

Update 16 (3) (May/June): 47 – 52.

Thomas, Jack Ward, Jerry F. Franklin, John Gordon, and K. Norman Johnson. 2006.

“The Northwest Forest Plan: Origins, Components, Implementation

Experience, and Suggestions for Change,” Conservation Biology 20 (2): 277 –

287.

Weber, Edward P. 2000. “A New Vanguard for the Environment: Grass-Roots

Ecosystem Management as a New Environmental Movement,” Society and

Natural Resources 13 (3): 237-259. [Read section on Grassroots Ecosystem

Management Movement]

Welch, Craig. 2009. “ The Spotted Owl's New Nemesis,” Smithsonian (January). http://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/the-spotted-owls-newnemesis-131610387/?page=2

Wilson, E. O. 1988. “ The Current State of Biological Diversity ,” [excerpted from] E. O.

Wilson and Frances M. Peter, Eds., Biodiversity. Washington, D.C.: National

Academy Press.

Session 6/Thursday, July 14: Species Loss around the Globe

Session 6 shifts gears and focuses our attention on species loss around the globe.

The first goal is to understand the many pressures and threats experienced by

6

species across the globe as well as the overall scope of the problem.

Precisely because many species, particularly fish and birds, cross national borders frequently as part of their regular migratory patterns, developing the capacity to deal effectively with species decline and loss demands that countries and nongovernmental organizations work together. A critical, early step in this direction involves the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA) of 1918, which recognized the harm being done by the large and growing demand for fashionable feathers and various types of avian meats (e.g., duck, geese, passenger pigeon). The Convention on

International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (CITES), signed in 1973, however, is the most important, and most comprehensive, of the international conventions devoted to species protection. We will also explore the powers of the ESA for protecting species in foreign territory, the challenges posed by globalization and invasive species, and the issues and dilemmas associated with global marine life. A team-based exercise will analyze and make recommendations on the best path(s) forward in the face of these challenges.

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) of Wild Fauna and Flora (signed in 1973; updated in 1979) (excerpt).

Economist. 2015. “Day of the Triffids,” (December 5): 59-60.

Hulme, Philip E. 2009. “Trade, Transport and Trouble: Managing Invasive Species

Pathways in an era of Globalization,” Journal of Applied Ecology 46: 10 – 18.

Invasive Species Specialist Group. 2004. “The Invasive Species Problem,” The World

Conservation Union (March 25). http://www.issg.org/#Invasives .

Montaigne, Fen. 2014. “Still Waters: The Global Fish Crisis,” National Geographic. http://ocean.nationalgeographic.com/ocean/global-fish-crisis-article/

Pimental, David, Rodolfo Zuniga, and Doug Morrison. 2005. “Update on the environmental and economic costs associated with alien-invasive species in the United States,” Ecological Economics 52: 273 – 288.

Pomponi, Shirley A. Ph.D., Chair, Ocean Studies Board, Division on Earth and Life

Studies, National Research Council. 2009. “ Managing Our Ocean and Wildlife

Resources in a Dynamic Environment: Priorities for the New Administration and the 111th Congress” (2009) (excerpt)

Summary, The Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA) of 1918.

Weber, Edward P. (forthcoming). “Global Oceans and Marine Life: Challenges and

Potential Solutions” (3 pages)

Team exercise – “Sorting Out Potential Solutions” o Which tools/policies are likely to be the most effective in the face of global challenges and why? (e.g., Measuring & reporting ocean health; marine reserve areas; raising consumer awareness; ocean fish farms; new treaties, trade and otherwise; or ….?)

Further Readings

McCauley, Douglas J., Malin L. Pinsky, Stephen R. Palumbi, James A. Estes, Francis H.

Joyce, and Robert R. Warner. 2015. “Marine Defaunation: Animal Loss in the Global

Ocean,” 347 Science 6219 (January 16).

7

Session 7/Tuesday, July 19: Species and Emerging Developments in the 21 st

Century

For growing segments of the American citizenry, and as reflected in federal and state environmental protection laws, there is no longer an overwhelming fear of wilderness, rather it is much closer to a strong embrace of wilderness and nature, along with acceptance that species and ecosystems necessarily add significant, ineluctable value, both to ecological health and the physical and spiritual well being of humans. Session 7 starts by reminding us once again of the direct connection between species health and human survival with an examination of the now welldocumented plight, and crisis, of bees. The session then moves to flesh out innovative new methods for providing species protection--the concept of Payment for Ecosystem Services, or PES, and the emergence of a new hybrid form of property rights that seeks to balance Locke’s property theory with environmentally based collective claims on property. Any consideration of endangered species in the 21 st century must also recognize the role played by the “rights of nature” movement, the intensification of outdoor recreational pursuits by Americans, and the emergence of amenity migrants and nature-oriented, amenity-based economies in some parts of the US.

Bees

Holland, Jennifer S. 2013. “The Plight of the Honeybee,” National Geographic News

(May 13). http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2013/13/130510honeybee-bee-science-european-union-pesticides-colony-collapse-epa-science/ .

PES

Costanza, R., dArge, R., de Groot, R., Farber, S., Grasso, M., Hannon, B., Limburg, K.,

Naeem, S., Oneill, R.V., Paruelo, J., Raskin, R.G., Sutton, P., van den Belt, M.,

1997. “The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital,”

Nature 387, pp. 253-260.

Kosoy, N., and E. Corbera. 2010. “Payments for ecosystem services as commodity fetishism,” Ecological Economics, 69(6), pp. 1228-1236.

Changing Property Rights

Cassuto, David, and Steven Reed. 2010. “Water Law and the Endangered Species

Act,” Social Science Research Network (July 28). http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1650241 .

Dan Tarlock, A. Dan. 2001. “The Future of Prior Appropriation in the New West,”

Natural Resources Journal 41: 769-793.

Rights of Nature

Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature. 2015. http://therightsofnature.org

Stone, Christopher D. 1972. “Should Trees Have Standing--Toward Legal Rights for

Natural Objects,” 45 Southern California Law Review 450.

8

Outdoor Recreation and Amenity Economies

Gosnell, Hannah, and Jesse Abrams. 2010. “ Amenity Migration: Diverse

Conceptualizations of Drivers, Socioeconomic Dimensions, and Emerging

Challenges,” GeoJournal. http://ceoas.oregonstate.edu/people/files/gosnell/Gosnell_Abrams_2010_G eoJournal.pdf

High Country News. 2014. On the Wild Edge. 46 (12) (July 21). (excerpts) An entire issue each year is dedicated to outdoor recreation. Find this one at http://edition.pagesuite-professional.co.uk//launch.aspx?eid=cdcc86fc-44ff-

4e47-8f1b-c849f3907e72

President’s Commission on Americans Outdoors (U.S.). 1987. Americans Outdoors:

The Legacy, the Challenge, with Case Studies: the Report of the President's

Commission. Washington, D.C.: Island Press.

(excerpt)

Further Readings:

Anderson, Terry L., and Donald R Leal. 1988. “ Inside Our Outdoor Policy,” Cato

Policy Analysis No. 113. http://www.cato.org/pubs/pas/pa113.html

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. 2005. Millennium Ecosystem Assessment:

Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Synthesis. Washington, D.C.: World

Resources Institute.

Nash, Roderick F. 1989. The Rights of Nature: A History of Environmental Ethics.

Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

Power, Thomas M. 1994. Lost Landscapes and Failed Economies: The Search for a

Value of Place. Washington, D.C.: Island Press.

Session 8/Thursday, July 21: Climate Change and ESA Reform Ideas

Finally, there is the specter of climate change and ideas for reforming the ESA.

Session 8 explores climate change, along with expectations for projected consequences, based on Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports, from the perspective of plant and animal species. Key to this is how climate change expectations challenge traditional policies for protecting species (e.g., wilderness areas), while also considering how the push for new carbon-free energy sources such as wind and solar power is creating new threats for species.

In a final cumulative exercise, teams will craft and present their best ideas for reforming the ESA in order to make it more effective in the battle to protect and ultimately recover threatened and endangered species.

Climate Change

Emmanuel, Kerry. 2012. What We Know About Climate Change. 2 nd ed. Cambridge,

MA: MIT Press. (this is only 120 pages long)

Long, Elizabeth, and Eric Biber. 2014. “The Wilderness Act and Climate Change

Adaptation,” Environmental Law 44: 623 – 694.

9

http://scholarship.law.berkeley.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3394&cont ext=facpubs

Mernit, Judith L. 2015. “Green Energy’s Dirty Secret,” High Country News (October

26). http://www.hcn.org/issues/47.18/green-energys-dirty-secret .

Park Science. 2011-2012. “[special issue] Wilderness Stewardship and Science.” http://www.nature.nps.gov/ParkScience/archive/PDF/ParkScience28(3)Wi nter2011-2012.pdf

.

ESA Reform

Adler, Jonathan H. 2009. “The Leaky Ark: The Failure of Endangered Species

Regulation on Private Land,” American Enterprise Institute (September 15).

Center for Biological Diversity. 2011. A Future for All: A Blueprint for Strengthening

the Endangered Species Act. (October).

Competitive Enterprise Institute. 1995. “The ESA: Bad for People, Bad for Species.”

(September 7).

Kettmann, Matt. 2013. “Why the Endangered Species Act Is Broken, and How to Fix

It,” Smithsonian.com (May 15). This is an interview with UC-Santa Barbara historian, Peter Alagona, about his book After the Grizzly. http://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/why-the-endangered-speciesact-is-broken-and-how-to-fix-it-63482436/?no-ist

Scientific American. 2014. “ Protect the Endangered Species Act [Editorial],” Vol. 310

(4) (March 18). http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/protect-theendangered-species-act-editorial/

Further Readings:

Cole, David, and Laurie Jung. Eds. 2010. Beyond Naturalness: Rethinking Park and

Wilderness Stewardship in an Era of Rapid Change. Washington, D.C.: Island

Press.

National Academy of Science. 1995. Science and the Endangered Species Act.

Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press.

U.S. Department of Interior. 2014. Climate Change Adaptation Plan. Washington,

D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. http://www.doi.gov/greening/sustainability_plan/upload/2014_DOI_Climat e_Change_Adaptation_Plan.pdf

10

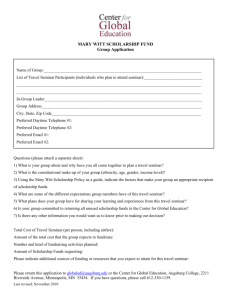

APPLICATION

SUNY Potsdam NEH Faculty Development Program

Summer Seminar for Faculty

Our summer seminar is offered to faculty of the Associated Colleges of the St. Lawrence Valley (SUNY Potsdam, Clarkson University, St.

Lawrence University, and SUNY Canton). The seminars provide area faculty with a valuable opportunity to enrich their knowledge of the subjects that they teach and research by working with distinguished outside experts, by studying alongside other instructors and scholars, and by undertaking individual projects of their own design.

There are up to eight participants selected for each seminar. Through research, reflection, and discussion with the seminar director and with other seminar members, participants have an opportunity to deepen their understanding of their field and improve their ability to convey that understanding to others. Participants are expected to take part fully in the work of the seminar and to complete all seminar projects.

Although writing may be encouraged by seminar directors, lengthy papers typical of graduate courses are not required. Seminar topics are broad enough to accommodate a wide range of interests. The topics allow participants to address significant questions, explore major texts, and extend their thinking beyond disciplinary concerns.

Eligibility

To be eligible applicants must be members of the faculty of SUNY

Potsdam or faculty of one of the Associated Colleges. Faculty members who have participated in previous SUNY Potsdam NEH Seminars are eligible to apply, but preference will be given to those who have not previously participated.

Selection Criteria

The selection committee will review applications and select participants on the basis of (1) applicant’s qualifications to do the work of the seminar and make a contribution to it; (2) the conception and organization of the applicant’s proposed study project in relation to the seminar topic; (3) the potential value of that project to other members of the seminar.

Stipend and Conditions of Award

11

Individuals selected to participate in the four-week seminar will receive a stipend of $2500 and an allowance of up to $500 for purchase of library books and travel related to the seminar project.

Participants are required to attend all seminar sessions and to engage fully in the work of the seminar. During the tenure of the seminar they may not undertake other professional duties that will interfere with their participation in the seminar (in particular, they may not be teaching Summer

School in tandem with participating in the seminar).

Immediately following the completion of the seminar, participants will be asked to submit an evaluation. In addition, ten months following the seminar, participants will provide an evaluation of the impact the seminar had on their profession development with particulars about papers given, scholarship published, and curricula projects implemented as a result of participation in the seminar.

Applications may be submitted by ordinary post to the NEH Program

Chair, Professor Geoffrey Clark, Dept. of History, Satterlee Hall, SUNY

Potsdam, 44 Pierrepont Ave., Potsdam, NY 13676. Alternatively, applications may be submitted electronically to the NEH Chair by email at clarkgw@potsdam.edu

. If submitting electronically, please include all application materials in the proper order in ONE Word file and include your last name in the file name.

APPLICATION MATERIALS

Please assemble your application by drafting the following documents:

1. Application Cover Sheet

Applicant's Title and Name

Home Address

Work Address

Telephones, Home and Work

Major Field of Applicant

2. Description of Objectives

Applicants must write an essay describing their objectives in applying to the seminar. Close attention should be given to the preparation of the description of objectives because it will be considered carefully by the

committee members as they make their selections. This essay should include any relevant personal and academic information. The essay should address reasons for applying to the seminar; the applicant's interest, both academic and personal, in the subject of the seminar, qualifications to do the

12

work of the seminar and to make a contribution to it; what the applicant wants to accomplish in the seminar; and the relation of the seminar to the applicant's professional responsibilities. The descriptive material provided about the seminar should be read carefully because the committee may request that particular information be given in the description of objectives.

The application essay should be NO MORE THAN three to four double-spaced pages. Be sure to address the following questions in relation to the proposed project: a. The specific study, research, or curricular project, including the basic ideas, problems, and questions that are of interest, with a specific concrete plan of investigation and a statement of its rationale. b. If the proposed project is part of a long-term undertaking, the present state of the larger undertaking and how the summer project fits in. c. The relation of the study to the applicant's immediate and long-range objectives as a teacher and scholar. d. Other information relevant to the proposed project.

3. Professional History

An application must include the professional history form (included below). A C.V. may be attached but will not be accepted in lieu of the professional history.

13

Professional History Form

1. Applicant’s Name and Institutional Affiliation (include department).

2. Applicant’s Field of Specialization

3. Full Time _______

4. Number of Years Teaching __________

Part Time _______

5. Education (list institutions, dates of attendance, major field and graduate degrees

6. Graduate Work in field of seminar

7. Teaching/Research interests in field of seminar

8. Sabbatical Leaves or other released time for research or study (specify when, where, and for what purpose)

9. Employment History (give institutions, dates, major responsibilities)

14

10. Courses Taught during the last two years

11. Academic Awards and Grants (mention any special awards or professional distinctions)

12. Previous SUNY Potsdam NEH Seminars

13. Most significant Publications and Professional Activities (This list

should be selective and not all inclusive.)

15