Ethnographic Research Methods - Towson University

advertisement

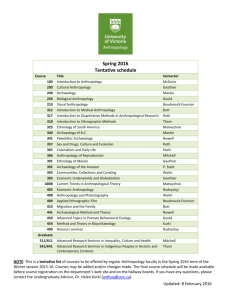

ANTH 380.001/ CLST 300.001 ethnographic field methods: networked anthropology instructor: Samuel Collins LA 3216; MW, 2-3:15 pm Office hours: Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, 10:30-11:30 am Room: LA 3334 Phone: x3199 (e-mail) scollins@towson.edu homepage: pages.towson.edu/scollins course description Once upon a time, the stories anthropologists told themselves about field research went something like this: after entering the field and gaining the trust of the “natives,” the anthropologist develops a “deep” understanding of culture, upon which she then returns to her own “culture” to communicate to her peers. As nearly 40 years of introspection in anthropology have borne out, there are many problems in this gloss on anthropological fieldwork, but one of the most glaring: the insistence on “entering” and “leaving” the site, as if the field were a room one could open and close a door on. In contrast, this course builds on the insight that we are always already connected in myriad (and perhaps very uncomfortable) ways to each other and to the places or the emergent phenomena that we might designate as our “field”. Instead of building an ethnographic methods premised on separation, this class introduces an alternative model for our connected age: a networked anthropology. Networked anthropology generates ethnographic data in multiple media. Here it overlaps with similar advances in different subdisciplines, including visual anthropology, public anthropology and action research. The difference is that a networked anthropology produces data that is simultaneously media to be appropriated and utilized by the communities with whom anthropologists work in order to connect to others (other communities, potential grantors, friends and family). And the opposite is also true—anthropologists are only generating data for their research in the space of their engaged commitments to communities to assist in their efforts to network to different audiences. Far from completely breaking with the past, network anthropology is itself (re)connected to anthropological history—amplifying some possibilities, counteracting other tendencies. Accordingly, the characteristics of networked anthropology both echo and contest other evocations of ethnography: 1. It’s about process. The point behind a networked anthropology is to articulate your work through the network, and that means posting up data, ideas and theories that are still in motion. The moment the book is printed, or the article published, then that process stops, and your work has been ossified—reified—into a singular, static work. Instead, networked anthropology takes a sometimes terrifying step into revealing ideas that are not fully formed. 2. It’s connected. What does it mean to be connected? It means more than just putting something up online. And it means more than your video going “viral”. In other words, being connected is entirely different than the 20th century media paradigm of either a) no one seeing your work; or b) everyone seeing your work. Instead, “connected” refers to the deliberate formation of a network of followers and sites you follow. It refers to the tagging you use to delineate and interpret your content for search engines and to attract new nodes and new connections. Mass media measures “audience” by demographic blocks; a networked audience is never undifferentiated, even if the number of page views scales into the millions. Each node delineates a particular quality of connection in a connected cluster of similar nodes. 3. It’s cross-platform. One of the biggest antecedents to networked anthropology is multimedia anthropology. A networked anthropology, however, is more nomadic, with the same material being used and re-used across different platforms, restlessly re-mixed and re-posted in different configurations. By crossing multiple platforms, meaning inevitably changes, and a networked anthropology seeks to take advantage of that while still admitting the shortcomings (and biases) of commercial platforms. 4. It’s collaborative. Once you’re decided on a networked anthropology, then you’ve given up some control and autonomy over your work. Your immediate collaborators (which include co-researchers, interlocutors and mentors), together with future collaborators (people who have connected to your work in some way through the networks you’ve formed) have measurable impacts on your work. 5. It’s recursive. What do you gain from a networked anthropology? One of the most important benefits is immediate feedback, which is not to say that people are necessarily commenting on content you’ve uploaded. But they are giving you feedback, even if it’s just in the form of site analytics. In return, that is data you need to incorporate into your research—it’s part of an emergent interpretation of your networked anthropology. 6. It’s about the long-term. Given the ephemerality of web content, the insistence on the long term seems disingenuous, but this is exactly the difference between viral media that makes the rounds of social networks over the course of a week and disappears and the anthropology we’re advocating. A networked anthropology establishes long-term connections for the benefit of everyone in the network. Premised on reciprocation, reciprocity, collaboration and recursivity, it only works if connections have an opportunity to develop over time. 7. It’s an ethical orientation. Networked anthropology engages heterogeneous ethical systems as it develops—the image is one of the network itself, edges multiplying along varied nodes. Perhaps the best metaphor for this anthropology is one deployed by James Faubion: “connectivity”. That is, in the course of connecting anthropologists, people and communities through networked media, we simultaneously connect to ethical problems and tensions inherent in both the “nodes” themselves (people, institutions, communities) as well as in the “edges”—our relationships with them. The creation of a linked, networked anthropology, then is simultaneously the elaboration of a networked ethics, and the ethical challenge of networked anthropology is to identify different ethical fields as they emerge across the field of ethnographic investigation. Potentially, then, we see several ethical nodes becoming salient to our work, but also acknowledge (and expect) that other issues will emerge. This course will, fittingly, adopt multiple perspectives on ethnography and networked anthropology. On the one hand, we will consider ethnography’s relationship--historical and theoretical--to cultural anthropology. We will consider the historical development of ethnography from early experiments in the mid-nineteenth century up to the present and link those putatively methodological developments to theoretical debates (then and now) in cultural anthropology. But the possibilities and problems with this ethnographic practice will lead us to consider other, networked alternatives—the possibilities for novel ethnographic practice nevertheless premised on the past. And while much of the emphasis on networked anthropology seems theoretical, it is ultimately about engaging in ethnographic practice. Throughout the semester, we will engage in a number of structured activities that bridge the gaps between everyday understanding and experiential, ethnographic knowledge. Additionally, students will take the first steps towards their own ethnography, following the building blocks of ethnographic research through their own research and through their connection to a long-term, networked anthropology of Baltimore: Anthropology By the Wire. Finally, the course will introduce possibilities for careers in qualitative research—another outcome of a properly networked world. Learning Outcomes Upon satisfactory completion of the course, students will be able to: 1). Communicate ethnographic methodology as arising in a context of anthropological theory. 2). Critically compare contemporary (and even experimental) methodologies through careful readings of ethnographies. 3). Utilize qualitative methods germane to the anthropological encounter: participant observation, interviews, life stories and visual anthropology. 4). Communicate research findings. required reading: The following texts are available through the University Store. Additional required readings are listed below in the class schedule. Chao, Emily (2012). Lijiang Stories. Seattle: University of Washington Press. Coleman, E. Gabriella (2013). Coding Freedom. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Novak, David (2013). Japanoise. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. Required software: 1). NodeXL: http://nodexl.codeplex.com/ 2). Gephi: http://gephi.org 3). Yoshikoder: http://sourceforge.net/projects/yoshikoder/?source=dlp graded assignments. Unless otherwise noted, all assignments should be uploaded to the appropriate discussion group on Blackboard. Failure to do so will result in a 2 point penalty per assignment. Methodology Assignments (Due on assigned days) Students will each complete six of eight short projects over the course of the semester. Projects will include 1) observations; 2) mapping; 3) blogging; 4) social network analysis;5) interviews; 6) transcription and coding. 100 pts. Baltimore Stories: Using data gathered during methodology assignments, together with data and media gathered for Anthropology By the Wire (anthropologybythewire.com), students will analyze and interpret some element of community in Baltimore in the content of multimedia. Emphasis should be on the efforts of groups of people to represent themselves as form of data production. Final papers will consider background, transcription, coding and interpretation, and should be from 10-15 pages in length. (50 pts.) Final Examination: (December 18th, 12:30-2:30 pm) Students will demonstrate their understanding of ethnographic methodologies by applying their knowledge to questions about the 3 ethnographies for the course. 50 pts. Explanation of Grading: A+ 186+ A- 180-185 B+ 174-179 B 166-173 B- 160-165 C+ 154-159 C 140-153 D+ 134-139 D 120-133 F <120 class schedule: 1st Week Introduction to the course and explanation of syllabus. (8/28) Characteristics of Cultural Anthropology Assigned reading: Novak, Introduction and Chapter 1 2nd Week Ethnographer and Flaneur (9/4) History of anthropological fieldwork Readings: Novak, Chapter 2 Burrell, Jenna (2009). “The Field Site as a Network.” Field Methods 21(2): 188-199. September 6—Change of Schedule Period Ends. 3rd Week Varieties of Ethnographic Research (9/9-9/11) Themes in contemporary ethnographic research Assigned Reading: Novak, Chps. 3-4 Assignment #1: Survey of Contemporary Ethnography 4th Week Collaborative Anthropology (9/16-9/18) Building a Network; Introduction to semester projects. Assigned Reading: Novak, Chap. 5-6 Coleman, Introduction and Chp. 1 Stewart, Michael (2013). “Mysteries reside in the humblest, everyday things.” Social Anthropology 21(3): 305-321. Baltimore Book Festival Project 5th Week Varieties of Observation (9/23-9/25) Structured and unstructured observation Assigned Reading: Novak, 7-Epilogue Coleman, Chps. 2-3 Wilkinson, Clare (2012). “An Anthropologist Among the Actors.” Ethnography 13(2): 144-161. Baltimore Book Festival (9/27-9/29) 6th Week Field Sites: Neighborhood Assessment (9/30-10/2) Site selection, anthropological ethics and participant observation Assigned Reading: Coleman, Chps. 4-5 Assignment #2: Festival Observations 7th Week Mapping (10/7-10/9) Library research methods Assigned Reading: Coleman, Conclusion and Epilogue Feldman, Gregory (2011). “If ethnography is more than participant-observation, then relations are more than connections.” Anthropological Theory 11(4): 375-395. Assignment #3: Neighborhood Assessment 8th Week (10/14-10/16) Social Media Assessment Assignment #4: Library Research. 9th Week Social Media and Place (10/21-10/23) Introduction to the Baltimore Stories Project Assigned Reading: Chao, Introduction and Chapter 1 Assignment #5: Social media assessment. 10th Week Informants, Hubs and Gatekeepers (10/28-10/30) Assigned Reading: Chao, Chps. 2-3 Assignment #6: Networked places. 11th Week Interviews (11/4-11/6) -Structured and unstructured. Assigned Readings: Chao, Chapter 4 November 6: Last day to withdraw with a grade of ‘W’ 12th Week Art and Deception in Transcription (11/11-11/13) Assigned Readings: Chao, Chapter 5 Saldana, Johnny (2008). “An Introduction to Codes and Coding.” Assignment #7: Interview transcription 13th Week Coding and Analysis (11/18-11/20) Assigned Reading: Chao, Conclusion. 14th Week Building Ethnographic Theory (11/25) Assigned Reading: Stewart, Kathleen (2012). “Precarity’s Forms.” Cultural Anthropology 27(3): 518-525. Assignment #8: Coding and analysis 15th Week Ethnographic Careers (12/2-12/4) Assigned Reading: Pandian, Anand (2012). “The Time of Anthropology.” Cultural Anthropology 27(4): 547-571. 16th Week (12/9-12/11) RESEARCH PROPOSALS DUE. FINAL EXAMINATION: Thursday, May 17th, 10:15 am-12:15 pm notes 1. Although exams and graded work will remain as stated above, I may have to change different readings or films on the syllabus throughout the semester. I will, in any case, try to give you ample warning of any syllabus changes. 2. Cheating and Plagiarism policy: Our department has the following policy on academic dishonesty: The faculty of the Department of Sociology, Anthropology & Criminal Justice take a strong stand against Academic Dishonesty of all forms. Academic dishonesty will not be tolerated in any class. It includes, but is not limited to, any form of cheating or unapproved help on an exam or academic exercise, copying someone else’s written work without citation, presenting fabricated information as legitimate, any unauthorized collaboration among students, or assisting someone to cheat in any way. All students have the ethical responsibility for doing their own work. A student who is uncertain about whether or not something constitutes academic dishonesty in a particular class has the obligation to see their instructor for clarification. Consistent with university policy, the minimum penalty for academic dishonesty in any form is determined by the individual faculty member in each class, and may consist of “a reduced grade (including “F” or zero) for the assignment; a reduced grade (including “F”) for the entire course,” or other options as stipulated in Appendix F of the Undergraduate Catalog. Students who are charged with academic dishonesty must remain enrolled in the course and cannot withdraw. Instructors who make the determination that academic dishonesty has occurred will notify the student in writing of the finding, the penalty, and the process for appeal. The same written notice will be forwarded to the Office of Judicial Affairs on campus, the Dean of the College of Liberal Arts, and to the Chair’s Office in the department. Academic Dishonesty undermines the legitimate efforts of students and involves serious repercussions. The faculty of the department urge all our students to act with integrity with regard to work submitted. (Approved Spring 2004) In addition, Students are expected to familiarize themselves with the University’s policy: http://wwwnew.towson.edu/provost/resources/studentacademic.asp At a minimum, students who plagiarize in this class will receive an “F” for the assignment. 3. Students who have, or suspect that they may have, a disability should seek services through Disability Support Services. Students must be registered with DSS and receive written authorization to obtain disability-related accommodations. If you need accommodation due to a disability, please visit DSS for guidance. The office is located at 7720 York Road, AD 232, Ph: 4-2638 or 3475. 4. Students may not repeat this course more than once (make a third attempt at this course) without the prior approval of the Academic Standards Committee. Please call 4-4351 or visit ES 235 for more information. 5. Late assignments: Late assignments will be accepted at ½ credit (1-2 days late) or ¼ credit (34 days late). After 4 days, late assignments will no longer be accepted. 6. Make-up Work: Under extraordinary circumstances, documented by physicians, police, etc., students may be allowed to make-up missed work. 7. Students who are disruptive may be dismissed from class. 8. Emergency Statement (TU Office of the Provost) In the event of a University-wide emergency course requirements deadlines and grading schemes are subject to changes that may include alternative delivery methods, alternative methods of interaction with the instructor, class materials, and/or classmates, a revised attendance policy, and a revised semester calendar and/or grading scheme. In the case of a University-wide emergency, please refer to the following about changes in this course: pages.towson.edu/scollins Email: scollins@towson.edu o For general information about any emergency situation, please refer to the following: 1. Web Site: www.towson.edu 2. Telephone Number(s) 3. TU Text Alert System: This is a service designed to alert the Towson University community via text messages to cell phones when situations arise on campus that affect the ability of the campus to function normally. Sign up: http://www.towson.edu/adminfinance/facilities/police/campusemergency / explanation of grading Consistent with University policy, the following grades will be assigned according to the designated criteria: A: A superior performance surpassing assigned work in unique and novel ways and integrating diverse ideas from a wide range of sources in addition to those discussed in class. AB+ B: Excellent work surpassing the expectations of the assignment and demonstrating initiative and a willingness to move beyond the basic requirements of the assigned work. BC+ C: Satisfactory work meeting all basic requirements of the assignment. D+ D: Work in some way less than satisfactory. Although conforming to basic requirements in some way, the completed work is nevertheless not a coherent response to the assignment. F: A profoundly unsatisfactory performance which doesn't meet the intent of the assignment at any level.