Nitrate Nitrogen in Springs - Howard T. Odum Florida Springs Institute

advertisement

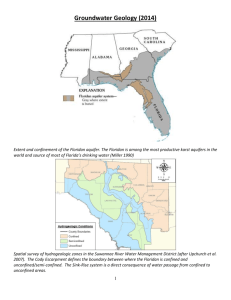

Howard T. Odum Florida Springs Institute Florida – “Land of 1,000 Springs” Introduction Florida has the greatest assemblage of artesian springs in the world, with over 1,000 springs documented to-date. Florida also has the largest number of first-magnitude springs (33 counting river rises) with historic average flows exceeding about 65 million gallons per day, and the largest individual spring groups with flows over 500 million gallons of groundwater per day (Figure 1). The largest of these springs and spring groups are well known - Silver, Wakulla, Ichetucknee, Weeki Wachee, Homosassa, Rainbow, Crystal, Manatee, Blue, Wekiwa, etc. - and almost every Floridian remembers the first spring they visited and when that visit occurred. The importance of these springs may seem intangible. Yet, the value of springs can be measured, both in economic terms for water supply and recreational enjoyment, and in their environmental services that support water-dependent biotic communities. Healthy springs depend upon plentiful and pure groundwater. Florida has extensive laws that were intended to protect the quality and quantity of the state’s surface and groundwaters. While these laws provide a framework that, if fully enforced, could protect springs from further degradation, they have not been effective todate from preventing significant impairment in spring flows and water quality. For this reason it is essential to pass additional legislation that specifically mandates and funds protection and restoration of Florida’s springs. During the past half century, declines in the health of our springs have become highly visible and well-publicized. Life-style changes are needed to reduce the human-induced impacts imposed on springs such as reduced flows and worsening water quality. Public education is also needed so decision-makers and the general public have a better understanding of “what we know” about Florida’s springs, both in terms of their normal functions and with regard to human-induced stresses that are changing them. Prudent and sustainable groundwater management is essential to protect the functions and values of springs into the foreseeable future. Here’s a brief overview of what we currently know about key environmental requirements that maintain our local springs; how changing environmental conditions are altering these springs; and recommendations for effective and cost-efficient solutions for restoring the health of our springs and aquifer, the foundation of a healthy economy. 1 Howard T. Odum Florida Springs Institute Figure 1. Location of the first magnitude springs of Florida 1the distribution of known springs in Florida as of 2000 . Scott, T.M., G.H. Means, R.C. Means, and R.P. Meegan. 2002. First Magnitude Springs of Florida. Florida Geological Survey Open file Report No. 85. Tallahassee, Florida. 1 2 Howard T. Odum Florida Springs Institute Economic and Natural Value The Florida Park Service estimates that in 2012-13, the 165 Florida state parks generated direct economic impacts of $1.2 billion and supported more than19,000 jobs. The 24 state parks that are centered on artesian springs had more than 3.1 million visitors, created an annual direct economic impact of about $127 million, and supported over 2,400 jobs during this same period. This recurring economic impact is equivalent to an endowed value over $4 billion and continues without expense to society. In addition to these easily quantifiable economic benefits, examples of less tangible “ecosystem services” provided by clean and plentiful groundwater and springs include: Water quality purification. For example, the Ichetucknee River continually receives groundwater contaminated with nitrate nitrogen from excess crop and landscape fertilization in the springshed. Natural biological processes in the spring run effectively assimilate about 120 tons of nitrate nitrogen each year. At an estimated cost of $50 per pound of nitrogen removal in conventional wastewater treatment systems, this natural purification function alone is worth nearly $5 million each year. Clean and abundant groundwater is arguably the most important “natural resource” in Florida. The state pumps about 4.2 billion gallons each day from groundwater aquifers. If this inexpensive water supply becomes depleted or contaminated, the next most cost effective source is surface water from rivers and lakes at an estimated average cost to collect, treat, and supply of roughly twice as much as groundwater. If the inexpensive groundwater supply is exhausted or contaminated through saltwater intrusion, the next most viable option is desalinization of brackish groundwater or seawater at a cost of more than ten times that of our current groundwater resources. The majority of the rivers in North and Central Florida (e.g., the St. Johns, Hillsborough, Suwannee, both Withlacoochees, Wakulla/St. Marks, etc., Apalachicola are predominantly spring-fed during periods of low rainfall. These rivers will stop flowing and lose their economic, biologic, and recreational values when their spring headwaters stop flowing or are polluted with excessive nutrients. Human Consumptive Water Uses and Spring Flow Florida Spring Fact: There is no “threshold”- all human consumptive water uses in a springshed reduce spring flows. Florida’s springs are characterized by a high flow of transparent, artesian groundwater. Clearly, the pure, unpolluted ground water itself is the most important component of these springs. Nearly every aspect of a spring, from the basin size and shape, to the fish, other wildlife, and plants in the spring run, and the public uses of the spring, are dependent upon this flow of pure water. The number one objective of springs’ protection must be the protection of the quantity and quality of water in that spring. Every human use of water in a springshed – the area of land that recharges water to a spring – to some degree reduces the ground water flow to springs in that springshed. Every 3 Howard T. Odum Florida Springs Institute domestic, agricultural, commercial, and public water supply well, shallow or deep, large or small, uses some water that would otherwise discharge through the Floridan aquifer into artesian springs. When Florida’s human population was relatively low, the changes in flow in springs due to these human consumptive uses were often not detectable. This was true in light of the natural fluctuations that occur every year in the amount of rainfall that naturally recharges the aquifers that feed these springs. That apparent absence of a human effect on spring flow is no longer the case in much of Florida. It is likely that most artesian springs in Florida are experiencing declining flows as a result of human groundwater uses. One documented example of a decline in spring discharge can be observed in the long-term data collected from Wekiwa and Rock springs (Orange County) near Orlando (Figure 2). 100 95 Intera 2006 (Predicted) Measured 90 Annual Mean Flow (cfs) 85 y = -0.3124x + 688.31 R2 = 0.4654 80 75 70 65 60 Minimum Annual Mean Flow = 62 cfs 55 50 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 Year Figure 2. Time series plot of annual aver age flows at Wekiwa Spring compared to the existing St. Johns River Water Management District minimum annual mean spring flow of 62 cfs established in 1991 2 The magnitude of the contribution of human groundwater use on this multi-decadal decline in spring flows is even open to some question due to the natural variability in rain and resulting aquifer recharge. Unfortunately by the time flow reductions become obvious in 2 Wetland Solutions, Inc. (WSI). 2007. Human Use and Ecological Water Resource Values Assessments of Rock and Wekiwa Springs (Orange County, Florida) Minimum Flows and Levels. St. Johns River Water Management District Special Publication SJ2008-SP-2, Palatka, FL. 192 pp. 4 Howard T. Odum Florida Springs Institute springs, they are often so great that significant ecological values and functions have already been lost. Nitrate Nitrogen in Springs Florida Spring Fact: The concentration of nitrate nitrogen, a recognized pollutant in surface and ground waters, is rising rapidly in response to agricultural and urban development. The increase in the human population in Florida and the corresponding land use changes resulting from that population increase are changing the quality of our artesian ground waters (Figure 3). An increase in nitrate nitrogen concentrations in the groundwater, almost state-wide, is one of the most shocking environmental consequences of the past half century of agricultural and urban development (Figure 4). While Florida has been known nationwide as a state with strict environmental protection standards, much of the state’s focus has been on protecting surface waters, with the tradeoff that pollutants such as nitrogen had to go somewhere else and often into the ground. Figure 3. Population growth (diamonds) in Hernando County, Florida and nitrate nitrogen concentration (triangles) at Weeki Wachee Spring from 1923 to 2006 3 Florida Springs Task Force 2006. Florida Springs - Strategies for Protection and Restoration. Prepared for the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. 3 5 Howard T. Odum Florida Springs Institute Figure 4. Nitrate-nitrogen contamination in Florida’s groundwater resources as measured in monitoring wells between 2000 and 2004by state and federal agencies (prepared by Wetland Solutions, Inc.). This trade-off to protect surface waters from nitrogen contamination may have seemed like a good idea at one time, but it is now clear that the state’s regulations have not adequately protected ground water resources. Throughout the karst areas of north and central Florida where artesian springs are common, groundwater nitrate nitrogen concentrations have increased from a normal background of less than 0.02 parts per million to widespread concentrations over 1.0 parts per million (a fifty-fold increase),with localized hot spots greater than 10 parts per million – the USEPA drinking water standard for nitrate. These increases in groundwater nitrate concentrations are not only a threat to drinking water supplies for humans but are also polluting surface waters where high-nitrogen artesian water discharges from springs. Springs that evolved over tens of thousands of years with a nitrate concentration of less than 0.05 parts per million (mg/L) are now experiencing a 1,500 to 20,000 percent increase in the concentration of this macronutrient, accompanied by the loss of native submerged aquatic vegetation and the excessive growth of filamentous algae. Even if all human-controlled nitrogen pollution sources were stopped today, nitrate nitrogen pollution in the Floridan aquifer and in our springs will take years to decades to reverse. 6 Howard T. Odum Florida Springs Institute Promoting Effective Springs Legislation General Springs Protection/Restoration Goals These general goals summarize the conclusions about what we need to do to protect and restore Florida’s springs based on the detailed springs facts described below. They do not reflect exactly what is in the proposed springs’ legislation but they are consistent with the legislation: Identify and map springsheds for all first magnitude springs and spring groups (Outstanding Florida Springs) and their Spring Protection Zones (areas of aquifer vulnerability); Reduce all sources of nitrogen (N) loading in Spring Protection Zones to achieve state numeric nutrient standard of <0.35 mg/L of nitrate-N at vents of Outstanding Florida Springs; Reduce permitted groundwater pumping throughout the Floridan Aquifer as needed to restore Outstanding Florida Springs average flows as necessary to prevent environmental harm (approximately >95 percent of average historic springs discharge); Direct the Florida Geological Survey to prepare an annual report to the Florida Legislature to document the environmental conditions in the Outstanding Florida Springs and summarize progress on achieving the water quality and quantity goals listed above. Recommended Talking Points These are the minimum talking points you should try to convey during each meeting with a State legislator concerning springs protection legislation: A springs protection bill is currently being prepared by Senators David Simmons, Charlie Dean, Alan Hays, Wilton Simpson, and Bill Montford. You are on a key Committee that will consider the Simmons legislation and we would appreciate your support for the bill. Springs are in terrible shape, due to declining flows and pollution, and they’re not getting better. The draft Simmons bill offers important new protections for springs: (1) it provides that currently compromised springs shouldn’t be “harmed” by further water withdrawals and (2) it restricts pollution sources in designated springs protection zones. Opponents of the Simmons spring bill will argue that current regulatory tools will protect springs. These include Minimum Flows and Levels (MFLs) and BMAPs (Basin Management Action Plans). The fact is that these well-intentioned tools have not provided sufficient protection and show no prospect of leading to springs recovery any time soon. 7 Howard T. Odum Florida Springs Institute With respect to water quality, for example, many of the BMAPs depend heavily on use of Best Management Practices by agricultural operations. Best Management Practices can be helpful, but we know that existing best management practices in porous, high-recharge areas do little to protect springs. With respect to water quantity, we appreciate the fact that Water Management Districts are accelerating their work on MFLs and are working together more effectively across district boundaries. However, there is no indication that these changes will be enough to replenish the aquifer and its springs. To date no degraded spring has graduated from these programs and been declared healthy. Key Senate Committees Once filed, Senator Simmons’ springs’ bill will likely be referred sequentially to the following three Senate committees. Twenty-eight of the forty members of the Senate serve on at least one of these three committees. District office locations are provided below as well. Senate Environmental Preservation and Conservation Committee Charles S. "Charlie" Dean, Sr. (R) – CHAIR - Inverness Joseph Abruzzo (D) – VICE CHAIR - Wellington Thad Altman (R) - Melbourne Dwight Bullard (D) – Cutler Bay Andy Gardiner (R) – Orlando Denise Grimsley (R) - Sebring Jack Latvala (R) - Clearwater Wilton Simpson (R) – New Port Richey Darren Soto (D) - Kissimmee Senate Agriculture Committee Bill Montford (D) – CHAIR – Tallahassee Dwight Bullard (D) – VICE CHAIR – Cutler Bay Jeff Brandes (R) – St. Petersburg Bill Galvano (R) - Bradenton Rene Garcia (R) - Hialeah Denise Grimsley (R) - Sebring Maria Lorts Sachs (D) – Delray Beach Senate Appropriations Committee Joe Negron (R) – CHAIR – Palm City Lizbeth Benacquisto (R) – VICE CHAIR – Ft. Myers Aaron Bean (R) -Jacksonville Rob Bradley (R) – Orange Park Bill Galvano (R) - Bradenton 8 Howard T. Odum Florida Springs Institute Andy Gardiner (R) - Orlando Denise Grimsley (R) - Sebring Alan Hays (R) - Umatilla Dorothy L. Hukill (R) – Port Orange Arthenia L. Joyner (D) – Tampa Jack Latvala (R) – Clearwater Tom Lee (R) - Brandon Gwen Margolis (D) - Miami Bill Montford (D) - Tallahassee Garrett Richter (R) - Naples Jeremy Ring (D) - Margate Christopher L. Smith (D) – Ft. Lauderdale Eleanor Sobel (D) - Hollywood John Thrasher (R) – St. Augustine Key House Committees Potential Florida House action on springs legislation will likely come only after Senate action is completed. House action would initially occur in the Agriculture and Natural Resources Subcommittee of the State Affairs Committee, then in the full State Affairs Committee. Depending on the bill’s content, it could also be referred to the Rules Committee and to the Agriculture and Natural Resources Subcommittee of Appropriations. House Agriculture and Natural Resources Subcommittee of the State Affairs Committee Caldwell, Matthew H. “Matt” [R] – CHAIR – Lehigh Acres Goodson, Tom [R] – VICE CHAIR - Titusville Rader, Kevin [D] – RANKING DEMOCRAT – Boca Raton Beshears, Halsey [R] – Apalachicola Boyd, Jim [R] - Bradenton Edwards, Katie A. [D] – Sunrise Lee, Jr., Larry [D] – Ft. Pierce Pigman, Cary [R] – Sebring Pilon, Ray [R] – Sarasota Porter, Elizabeth W. [R] – Lake City Reed, Betty [D] – Tampa Rooney, Jr., Patrick [R] – Palm Beach Gardens Watson, Jr., Clovis [D] - Gainesville House State Affairs Committee Precourt, Stephen L. “Steve” [R] – CHAIR - Orlando Grant, James W. “J.W.” [R] – VICE CHAIR - Tampa Albritton, Ben [R] – Bartow Boyd, Jim [R] – Bradenton Brodeur, Jason T. [R] – Sanford Caldwell, Matthew H. "Matt" [R] – Lehigh Acres 9 Howard T. Odum Florida Springs Institute Combee, Neil [R] – Auburndale Eagle, Dane [R] – Cape Coral La Rosa, Mike [R] – Saint Cloud Raburn, Jake [R] – Valrico Rader, Kevin [D] – Boca Raton Rangel, Ricardo [D] – Kissimmee Stewart, Linda [D] – Orlando Taylor, Dwayne L. [D] – Daytona Beach Waldman, James W. "Jim" [D] – Coconut Creek Watson, Jr., Clovis [D] – Gainesville Workman, Ritch [R] – Melbourne 10