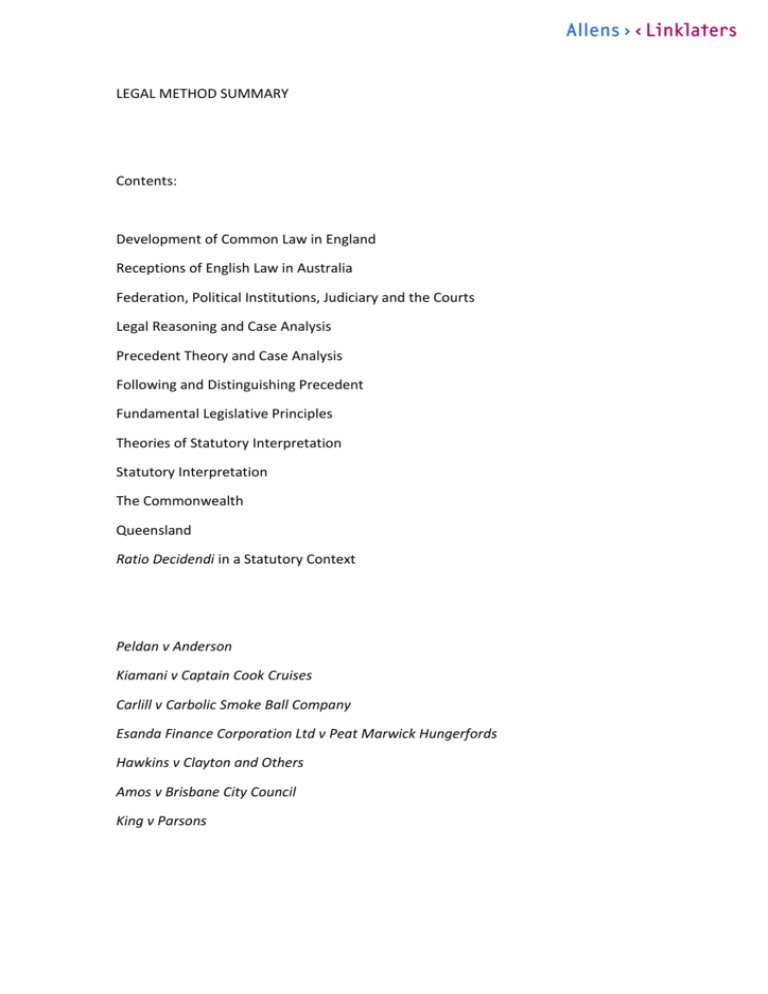

notes - The University of Queensland Law Society

advertisement