Workshop Report

advertisement

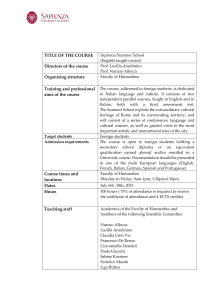

Jean Monnet Lifelong Learning Programme ‘Cross-Border Litigation in Italy’ Workshop Report No 2 19th November 2012 "This project has been funded with support from the European Commission. This publication reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein." BACKGROUND On Monday 19th November 2012, academics from Italy and academics connected with the Centre for Private International Law met at the second of seven workshops dedicated to promoting the debate on how cross-border litigation functions across Europe. The purpose of the second workshop was to offer the opportunity for a free and frank exchange of ideas about crossborder litigation and the application of the harmonised private international law instruments from an Italian perspective. This report intends to provide a brief overview of the ideas that emerged from the workshop without attributing any views to any particular individual. Part I CROSS-BORDER LITIGATION IN EUROPE AND A VIEW FROM ITALY ON BRUSSELS I Cross-Border Litigation in Europe: Research Activities – Aims and Objectives Background issues were identified surrounding the development of private international law within Europe. European integration, the consolidation of industry and an increase in migration of people across Europe were put forward as reasons for the increase in cross border disputes. The success in private law within Europe so far has been the harmonisation of private international law instruments, with the intention to preserve the diversity in legal traditions. However Europe has gone a step further in trying to harmonise some procedural rules, which has proved difficult. Three questions were put forward for consideration in relation to Italy: Do litigants often bring cross-border claims in Italy? Do litigants often settle before going to trial and why? What problems arise most frequently in cross-border litigation? Six potential areas for future research were put to the floor for criticism. The importance of private international law for resolving cross-border disputes in family, civil and commercial matters, which may effect businesses, consumers and families, raises concerns as to the uniform application of the various private international law instruments across the Member States within the EU. The current European judicial architecture poses problems for litigants with disputes with an international element. Such litigants would have to take cross-border litigation risks and incur higher costs. The high costs and the high level of uncertainty could adversely affect cross-border claimants’ litigiousness, as a number of potential litigants may believe that the risks of litigation outweigh the benefits. Whilst Alternative Dispute Resolution appears to be a cheaper solution, which is advocated by the EU legislator, it is difficult to see how ADR could develop before case law precedents have been more clearly established. (Directive 2008/52/EC on certain aspects of mediation in civil and commercial matters OJ [2008] L136/3) The ability of the Court of Justice to deal appropriately with the private international law issues may be questioned. A review of the institutional architecture of the European judiciary may be key for creating “a Europe of law and justice”. The increased reliance on harmonised private international law instruments in the EU indicates that the interpretation should go to a special European Court or a specialised chamber of the Court of Justice. Empirical research was identified as being useful in order to get response from practitioners, in particular analysis of the relationship between litigants, the strategies employed and the expenditure for both parties in cross-border cases. However it was suggested that funding would be difficult to obtain for this purpose. Comparative study was put forward as valuable but only if it was of sufficient quality. It should take into account the dynamics of the rules, and the way they shape litigant’s tactics with regards to cross border actions in Europe. A cross-border consortium would be able to promote debate across boundaries in the targeted countries, identify country specific issues feeding them into cross-border debate and identify a workable solution for private international law in a European context. The need to get practitioners involved in the process was reiterated. Brussels I Two areas were put forward for discussion. The first was whether the Italian court rulings aligned with the European Court of Justice and the second looked at the Italian court rulings on certain interpretative issues on which the ECJ has not yet stated its position. Article 5(1)(b) of the Brussels I Regulation concerning the jurisdiction on sale of goods agreements and the definition of what constituted a “place in a Member State where the goods were delivered or should have been delivered” was discussed. The initial position of Italian case law was that the relevance to the place of delivery of the goods to the first carrier in compliance with article 31 CISG, is that the seller is not bound to deliver the goods to any other particular place. His obligation to deliver consists of handing the goods over to the first carrier for transmission to the buyer. The position of the Italian Supreme Court is that relevance for the purpose of the identification of the “place of delivery” and consequently of the place in which the jurisdiction must be established should apply to all obligations arising out of the agreement. The position of ECJ is that the “place of delivery” is “1) the place where, under the contract, the goods were delivered or should have been delivered or, in absence, 2) the place where the physical transfer of the goods took place at the final destination of the sales transaction.” With regards the interconnection between the lis alibi pendens and choice of court agreements there is harmony between the Italian case law and ECJ. In 2007 the Italian Supreme Court gave a ruling concerning the nonpayment of the consideration under an exclusive sale agency agreement in relation to which the defendant contests the jurisdiction of the Italian Court on the basis of a previous proceeding pending before a Portuguese Court arising from the same agreement. It was held that the Italian Court should apply art. 27 of the Regulation and stay proceedings until the Portuguese court has assessed its jurisdiction even in the presence of a choice of court clause in favour of the same (Italian) Court. In the Gasser case the ECJ stated that a court second seised whose jurisdiction has been claimed under an agreement conferring jurisdiction must nevertheless stay proceedings until the court first seised has declared that it has no jurisdiction. The position under Brussels I Recast is that under art 3(2) “Without prejudice to article 26, where a court of a Member State on which an agreement referred to in art 25 confers exclusive jurisdiction is seised, any court of another Member State shall stay the proceedings until such a time as the court seised on the basis of the agreement declares that it has no jurisdiction under the agreement.” How the Italian Courts have interpreted the Brussels I Regulation was then put forward for discussion. Article 5(3) of the Regulation concerning jurisdiction of the courts of the place where the harmful event occurred or may occur was the first point to be discussed. The Italian Supreme Court affirmed jurisdiction of the Italian Courts under art 5(3) of the Regulation in case no 8034 April 2011, concerning an offer of financial instruments by Irish and Swiss companies, which were referable to a Mr Madoff on the Italian market. Both the fact that the investment scheme did not provide for the prescribed separation between the manager and the custodian and that the inaccurate prospectus which was made available to potential investors in order to solicit investment were held to fall under art 5(3). In case no 5032 September 2011 concerning derivative transactions entered into by a public entity the exclusive jurisdiction of the Italian Administrative Court was affirmed as administration is excluded from the scope of the Regulation thus indirectly confirming art 22 of the Regulation. Conversely the European Court of Justice in Berliner Verkehrsbetriebe (BVG) v JPMorgan Chase Bank NA, Frankfurt Branch has held that “art 22(2) of the Brussels I Regulation must be interpreted as not applying to proceedings in which a company pleads that a contract cannot be relied upon against it because a decision of its organs which led to the conclusion of the contract is supposedly invalid on account of infringement of its statutes.” A case no 3568 February 2011 relating to damages to certain ferried goods belonging to an Italian company claimed against the bill of lading underwriter containing a choice of court clause in favour of the Courts of the People’s Republic of China found that there was non applicability of the regulation, thereby applying the relevant national rules and confirming the choice of court clause. The Court stated that the fact that the regulation is silent on the derogation of the member states jurisdiction does not mean in itself that the derogation is excluded, in any event within the limits in which the parties may derogate to the same under the Regulation. It was noted that the Recast of Brussels I Regulation does not explicitly deal with the derogation of member states jurisdiction. It was left to the Hague Choice of Court Agreements Convention to find a solution for the problem when the EU ratifies it. The final case to be put forward, no 5127 February 2002, concerned a decision given by a Greek court first seized affirming jurisdiction that had been disregarded by the second seized Italian Court. It was held necessary for the second seized Italian court to take the Greek decision into consideration, since it is a fully recognisable decision under article 33 of the Regulation. The cases presented, of which not all can be mentioned in this report are predominantly last instance cases and it was asked why the courts hadn’t requested preliminary rulings. It was noted that the Italian court has never requested a preliminary ruling, yet it was agreed that the Supreme Court should have asked for explanations. The reasoning for the court not requesting a preliminary ruling was put down to concerns over time and was not a trust issue. Part II CHOICE OF LAW IN OBLIGATIONS a. Rome I An assessment of how the Italian courts might apply the Rome I Regulation was considered, as the Italian courts have not yet had to make any decisions applying the Regulation due to the fact that it only came into effect in 2009. However several decisions have been rendered in application of the Rome Convention. Reference to these decisions were made, and compared to the potential outcomes had the same disputes been decided under the Rome I Regulation, also with a view, of course, to the relevant judgments rendered by the Court of Justice of the European Union. Under Article 3(1) Rome Convention on freedom of choice, where the choice of the governing law is not expressed, it must be demonstrated with reasonable certainty by the terms of the contract or the circumstances of the case. In 2010 the Cassazione (Corte di Cassazione, judgment 25 November 2010 No 23933) addressed the issue of an implied choice of the law that governed the employment contract between a German employer and an Italian employee. In the case at issue, the Court held that the law governing the contract was German law, and in doing so it pointed to a number of elements as indicating such an implied choice. Notably, the court pointed to the fact that the contract had been written in German, it had been drafted and entered into in Germany, it indicated the amounts due under the contract in German Marks, and finally it provided German health and pension benefits. The support of party autonomy in contracts was the core of the Rome Convention, as it is for the Rome I Regulation. The Convention’s provisions on the choice of the applicable law have been reproduced in the Rome I Regulation, which at Recital 11 states that: “The parties’ freedom to choose the applicable law should be one of the cornerstones of the system of conflictof-law rules in matters of contractual obligations.” However, unlike the Convention, where the choice must simply be expressed or demonstrated with reasonable certainty by the terms of the contract or the circumstances of the case, under the Rome I Regulation the choice must be “made expressly or clearly demonstrated by the terms of the contract or the circumstances of the case”. It was noted that the slightly different wording adopted within the Regulation apparently aims at narrowing the courts’ discretion and at facilitating predictability of the law governing the contract. It is therefore possible that the new wording in the Regulation will lead courts, including Italian courts, to be more cautious in applying this part of the provision thus reducing the scope of the concept of implied choice. As for the closest connection under Article 4 of the Rome Convention, the Tribunale di Udine (judgment 2 August 2002) displaced the presumption at Article 4(2) of the Convention, while trying to establish jurisdiction pursuant to Article 5(1) of the Brussels Convention. In a dispute between an Italian contractor (plaintiff) and an Austrian undertaking (defendant), where the contract was entered into in Austria, the construction works were to be carried out in Austria, the contract’s execution was subject to Austria’s technical regulations, the contract had been written in German, the amounts due were expressed in Austrian schillings and were to be paid at an Austrian bank account, the Italian court of first instance ruled that Austrian law (as opposed to the law of the characteristic performer’s habitual residence, i.e. Italy) governed the contractual relationship. However the Cassazione (Cassazione plenary session, 11 June 2001 No 7860) ruled that, pursuant to Article 4(2) of the Rome Convention, the characteristic performance has to be concretely determined based upon the circumstances of each single case. In a distribution agreement between an Austrian distributor (plaintiff) and an Italian supplier, to consider merely distribution as the characteristic performance (as a result of the fact that distribution is the non-monetary performance in an agency agreement) would be tantamount to overlooking a fundamental part of the contract: i.e., the function of exchange carried out with the contract. Accordingly, in the case at issue the characteristic performance was marked by the provision of the goods that were later to be distributed. As a result of the fact that the goods were being supplied in Italy, where they were also manufactured, the contract was governed by Italian law. Moving from the assumption that the dispute addresses a provision of goods rather than a distribution contract, the Cassazione’s outcome appears to be in keeping with the Rome I Regulation, whereby a contract for the sale of goods shall be governed by the law of the country where the seller has his habitual residence (Article 4(1)(a)). In a dispute over the breach of a contract between an Italian carrier and an Austrian client for the carriage of goods from Spain to Greece, the Cassazione (Cassazione plenary session, 3 May 2005 No 9106) ruled that the characteristic performance was the performance of the carrier. Accordingly, Italian law governed the contract. Pursuant to Article 5(1) of the Rome I Regulation, the law of the place of delivery as agreed by the parties (i.e., Greece) would likely govern the contract. The law of the habitual residence of the carrier (Italy) would not apply since neither the place of receipt (Spain), nor the place of delivery (Greece), nor the habitual residence of the consignor (Austria) was situated in Italy. In a dispute over the breach of a contract between an Italian architect and his German client for failure to pay, the Cassazione (Cassazione, plenary session, decree 27 April 2010 No 9965) ruled that, pursuant to Article 4(2) of the Rome Convention, in a contract for home improvement and building project in which negotiations were carried out in Italy and the architect was appointed in Italy where the assignment was also performed, the law governing the payment obligation was Italian law. This outcome appears to be in keeping with what is provided at Article 4(1)(b) of the Rome I Regulation. The provision at Article 6(2)(a) of the Rome Convention on the law governing individual employment contracts is fully reflected in Article 8(2) of the Rome I Regulation. The wording of the provision has slightly changed. While Article 6(2)(a) of the Convention provided that “Notwithstanding the provisions of Article 4, a contract of employment shall, in the absence of choice in accordance with Article 3, be governed: a) by the law of the country in which the employee habitually carries out his work in performance of the contract, even if he is temporarily in another country”, Article 8(2) of the Rome I Regulation provides that, absent the parties’ choice, “… the contract shall be governed by the law of the country in which or, failing that, from which the employee habitually carries out his work in performance of the contract”. The changes brought to the provision actually broaden the chances that the provision at Article 8(2) be applied in lieu of the subsidiary provision at Article 8(3) which provides that “Where the law applicable cannot be determined pursuant to paragraph 2, the contract shall be governed by the law of the country where the place of business through which the employee was engaged is situated”. Such added flexibility is the result of the fact that the country in which or from which the employee carries out his work is actually considered to be more likely to represent the (unitary) centre of gravity of the contract. In so far as the objective of Article 6 of the Rome Convention is to guarantee adequate protection for the employee, that provision must be understood as guaranteeing the applicability of the law of the State in which the employee carries out his working activities rather than that of the State in which the employer is established. It is in the former State that the employee performs his economic and social duties and it is there that the business and political environment affects employment activities. Therefore, compliance with the employment protection rules provided for by the law of the country where the employee performs his working obligations must, in as much as possible, be guaranteed. This approach is also in keeping with the ECJ’s case law on the jurisdiction in individual employment contracts pursuant to the Brussels I Regulation, whereby the Convention’s goal is to guarantee adequate protection to the employee as the weaker of the contracting parties (see, to that effect, Case C-383/95 Rutten [1997] ECR I-00057, paragraph 22, and Case C-437/00 Pugliese [2003] ECR I-3573, paragraph 18). As such, the application of Article 6(2) is facilitated by the EU legislator. Indeed, the criterion of the place of performance of the employee’s working obligations shall be interpreted autonomously: its meaning and scope must be established according to consistent and independent criteria in order to guarantee the full effectiveness of the Rome Convention in view of the objectives which it pursues (see, by way of analogy, Case C-125/92 Mulox IBC [1993] ECR I-4075, paragraphs 10 and 16). While addressing a motion to dismiss for lack of jurisdiction under Article 5(1) of the Brussels Convention (to which reference was made under Article 3 of the law reforming the Italian system of PIL, Law No 218/1995), the Court of Cassazione (in Cass. plenary session, 17 July 2008 No 19595) ruled that, in order to determine the place where the maritime worker habitually carries out his work and/or where the place of business through which he was engaged is situated, relevance must be given to the “nonoccasional territorial connections”, that is to say to the significant connections. In the case at issue, the Cassazione gave specific priority to the place where the operational unit was located and at the place where the main port of reference was situated. The Court further pointed out that the ship, although it could be considered as a plant or an establishment, however does not have any relevance as for the determination of the applicable law: in fact, a ship cannot be identified as a “place”, given that it is capable of moving. Citing this very judgment, the following year the Cassazione (Cass. plenary session, 20 August 2009 No 18509) granted motion to dismiss for want of jurisdiction in a case between a steward and his employer (a Belgian airline). In the case at issue, the employer only had a desk in Italy, where it checked (and not issued) tickets and where it gathered personnel and passengers. The Cassazione refused to take into consideration for jurisdictional purposes the employee’s statement that he was working at the airline’s Italian office, from which the plaintiff took off for his flights and to which he returned. The Court did not consider these elements as sufficient to assess that the airline company had a detached organizational unit in Italy. To the contrary, the Court traced such an organizational unit back in Belgium as a result of the more significant connections that the working relationship bore with that State. The Court pointed at the fact that the working relationship’s ties to Italy were purely functional to the performance of the employee’s contractual obligations, and that the working relationship was structurally tied to Belgium as a result of the fact that, not only the airline’s seat was in that State, but that the actual relationship between the employer and the employee was being carried out in that State (inter alia, the court pointed to the fact that in the working relationship taxation, as well as pension and health benefits were granted according to Belgian law). Accordingly it granted the motion to dismiss. The Cassazione’s approach appears to have anticipated the ECJ’s recent ruling in Koelzsch (Case C-29/10, not yet published), where the ECJ was asked whether the rule under Article 6(2)(a) of the Rome Convention is to be interpreted as meaning that, in the situation where the employee works in more than one country, but returns systematically to one of them, that country must be regarded as that in which the employee habitually carries out his work. As the Court pointed out, in the light of the objective of Article 6 of the Rome Convention, the criterion of the country in which the employee “habitually carries out his work” must be given a broad interpretation, while the criterion of “the place of business through which [the employee] was engaged”, set out in Article 6(2)(b) of the Regulation, ought to apply in cases where the court dealing with the case is not in a position to determine the country in which the work is habitually carried out. It follows from the foregoing that the criterion set out in Article 6(2)(a) of the Rome Convention can apply also in a situation where the employee carries out his activities in more than one Contracting State, if it is possible, for the court seized, to determine the State with which the work has a significant connection. As the Court highlighted, this interpretation is consistent also with the wording of the new provision introduced by the Rome I Regulation. As the ECJ stated, the seised court shall determine in which State is situated the place from which the employee carries out his transport tasks, receives instructions concerning his tasks and organises his work, and the place where his work tools are situated. The court must also determine the places where the transport is principally carried out, where the goods are unloaded and the place to which the employee returns after completion of his tasks. Accordingly, Article 6(2)(a) of the Rome Convention must be interpreted as meaning that, in a situation in which an employee carries out his activities in more than one Contracting State, the country in which the employee habitually carries out his work in performance of the contract, within the meaning of that provision, is that in which or from which, in the light of all the factors which characterise that activity, the employee performs the greater part of his obligations towards his employer. This approach appears to be in keeping with that adopted by the Cassazione in 2008 and 2009. Under Article 16 of the Rome Convention, the application of a rule of the law of any country specified by the Convention may be refused only if such application is manifestly incompatible with the public policy of the forum. This provision is exactly mirrored at Article 21 of the Rome I Regulation. And, as stated by the ECJ with reference to both the Brussels Convention and the Rome Convention (cf. Case 102/77 Hoffman [1978] ECR 01139, and Case C-78/95 Hendrikman [1996] ECR I-04943), as a result of the principle of predictability and uniformity of the applicable law, the public policy clause may be opposed to the rules of the law otherwise applicable only in truly exceptional cases. As for public policy in Italian courts under the Rome Convention, in a dispute between an employer and his employee who had worked in the U.S. where the working relationship was governed by U.S. law (and notably, the laws of the State of New York), the Corte di Cassazione, (judgment 11 November 2002 No 15822) held that, pursuant to Article 6(2) of the Rome Convention, a foreign law that does not grant any protection against firing an employee without just cause clashes against public policy. b. Rome II There is no case law in Italy concerning Rome II. However a survey of case law under the former legislation applicable in Italy was given, including article 62 of the Italian law on private international law and article 5(3) of Brussels I Regulation. The areas for analysis were the general rule of locus damni art 4(1) of the Brussels I Regulation, the economic and moral damages, common residence, choice of law and punitive damages. Under article 62 the law of tort was where the damage occurred. This applied to citizens who are resident in the same state, the law of that state is applicable. It is possible to choose between lex damni and locus actus. Under Italian law the lex loci actus has been seldom used. An example of a case using lex loci actus was a claim for damages for forced labour in Germany during World War II. The court held that the relevant harmful event was the capture in Italy therefore the plaintiff argued that Italian law was applicable. The facts were interpreted to avoid splitting the tort into harmful event and damages. In a case concerning an Italian citizen who went to the US for an operation and returned to Italy with the HIV virus the question was where had the damage occurred. The patient claimed the harmful event had occurred in US, but that the damage had occurred in Italy. The court dismissed this and said that the harm had occurred in the US. This case shows that Italian law of private international law is in line with the Regulation. With regards to economic loss and moral damages there was a case concerning the death of an Albanian worker in Spain where the Italian court decided that there should not be unjustified enrichment. It was decided that the damages should be calculated according to Albanian purchasing power. Recital 3 Rome II states that the court should take all relevant circumstances of the victim into account but this only applies to road traffic accidents. In another case involving the death of Italian citizens in a Cuban air crash. The relatives claimed damages in the Italian court. In theory the applicable law should be Cuban, however the court decided that the damage caused to the relatives was autonomous which gave the Italian courts jurisdiction and the applicable law was Italian. It should be noted that damages are not permitted under Cuban law. The general rule in Rome II does not favour the victim so this could be a difference in approach. Common habitual residence under Article 4(2) of the Regulation was known under the earlier Italian law, but seldom applied. A case concerned two Italians and 1 Spanish citizen in a car accident in Spain. The Italian court said that they could apply Italian law due to common residence. Only material facts should be considered. The court showed that the Spanish citizen was not party to the proceedings as the initial car accident had not involved them. Choice of law was previously not admitted. First case on Rome II concerns choice of law. Tacit choice of law in a car accident case. Culpa in contrahendo is traditionally tort under Italian law (art 12) so in theory there is no problem with classification. However it could be a problem in applying a solution under Rome II. In all the decisions, which were examined, there has been no reference to underlying contracts. There could be a problem if the law of contract has to be applied. Punitive damages are traditionally contrary to public policy. Damages are meant to compensate for actual prejudice and not to punish someone. There could be a potential problem for cases that are governed by an applicable law that supports punitive damages, but this is allowed for by recital 32 to Rome II. Part III CROSS-BORDER LITIGATION IN FAMILY MATTERS a. Brussels IIa and Maintenance The impact of the EC Regulations No 2201/2003 and No 4/2009 on the Italian legal system was assessed. These two Regulations are closely connected, since an action in matrimonial matters or concerning parental responsibility is very likely to be accompanied by a claim for maintenance as an ancillary claim. Recent Italian case law illustrates the coordination between the two Regulations, insofar as divorce or legal separation proceedings and maintenance proceedings connected thereto can be brought before the courts of one Member State (Tribunale di Milano, 10 July 2012). Jurisdiction and recognition of decisions on matrimonial matters As far as jurisdiction on matrimonial matters is concerned, the entry into force of EC Regulation No 1347/2000 actually resulted in a partial restriction of the scope of jurisdiction of Italian courts, since it ruled out some exorbitant grounds, such as the nationality of one of the spouses and the place of celebration of the marriage, and severely limited the relevance of the habitual residence of the applicant. The application of the criterion of habitual residence did not seem to give rise to practical problems for Italian courts, as it overlaps with the similar notion already known to national law. The EC Regulation No 1347/2000 did not provide for any major innovation in matters of recognition of decisions: under Italian law the principle of automatic recognition of decisions had been already extended also to matrimonial matters and Italian officers were requested to update the civil-status records as a consequence of a foreign judgment without any special procedure. Jurisdiction and recognition/enforcement of decisions about parental responsibility As regards parental responsibility and child abduction matters, national case law is far more abundant. Again, the scope of Italian jurisdiction has been severely restricted after the entry into force of the Regulation. The Italian Supreme Court interpreted article 8 of the EC Regulation No 2201/2003 so as to emphasize the exclusivity of the forum of the habitual residence of the child, as it is intended to preserve the best interests of the child. As a consequence of the exclusivity of the forum of the habitual residence of the child, a narrow interpretation of other provisions of the Regulation prevailed. In particular, the prorogation of jurisdiction was in many cases ruled out under article 12 of the Regulation, because it had not been accepted by one of the parents. Only one judgment referring to article 15 of the Regulation is reported, as yet. Italian courts were also faced with several cases concerning child abduction matters. The most sensitive issue concerns article 11 of the Regulation, as shown by the ECHR judgment in Sneersone and Kampanella case of 12 July 2011. It is, of course, very difficult to strike a balance between the necessity of granting the return of a child unlawfully removed or retained and the risk of psychological harm for the child, recalled by article 13 of the 1980 Hague Convention as well. However, Italian case law shows that national courts are usually willing to engage in the necessary comparative analysis and quite often refused to order the return of the child on the ground that reasons for non-return existed under article 13 of the 1980 Hague Convention (Corte di cassazione No 16549/10, No 11156/12). In other cases concerning article 11 of the Regulation the Corte di cassazione emphasised the right of the child to be heard in proceedings concerning his/her return, compelling lower courts to allow the hearing. However, in a recent judgment the Corte di cassazione took the view that hearing the child is not mandatory when it is impeded by the parent abductor (see judgment No 11156/12). On the other hand, Italian courts were not confronted with significant problems concerning the regime of enforcement of decisions in matters of parental responsibility. The general regime draws inspiration from the 1968 Brussels Convention, so that it is well known to national courts. The special regime of decisions in matters of rights of custody and return of the child seems to be much more challenging, especially because it seems to deprive the Member State of enforcement of every power to verify the requirements set forth by the Regulation for the circulation of those decisions. No case law is, however, reported on the subject matter. Jurisdiction and recognition/enforcement of decisions in matters relating to maintenance obligations In matters relating to maintenance obligations EC Regulation No 4/2009 entered into force only recently and as yet only one judgment is reported to have recalled it. However, it is possible to elaborate on the impact of some major innovations contained therein for the Italian legal system. As regards the rules on jurisdictional competence, the most significant innovation brought about by the Regulation will be the introduction of the socalled forum of necessity. Such a head of jurisdiction is actually new to the Italian legal system, because it does not rely upon a link between the dispute and a State, but is aimed at the protection of the right of action. The possible lack of predictability of the forum of necessity will probably lead Italian courts to a very narrow interpretation of article 7. Also the general regime of recognition and enforcement of decisions, providing for the abolition of exequatur proceedings, is going to introduce important innovations, since the Member State of origin is requested to issue a mere extract from the decision and the defendant is only granted the right to apply for a subsequent review in the Member State of origin. The abolition of every procedure of review in the Member State of enforcement gives rise to some apprehensions: it is, however, far from certain how a balance can be struck between the abolition of exequatur proceedings and the need for the protection of fundamental procedural rights. Questions were put forward concerning fundamental rights and the need to take it into account when recognising and enforcing decisions. It was noted that the ECJ is reluctant to take fundamental rights into consideration when using Brussels IIa. b. Succession The possible impact of the Succession Regulation on the Italian system of private international law was examined. As it currently stands cross border succession is dealt with almost entirely by domestic law. Italy is not party to any of the relevant Hague Conventions. Four inter-related areas were identified for analysis. The first unity and universality of succession, second the coincidence of jurisdiction and the applicable law should be facilitated, third party autonomy and finally an area that is of importance within Italy, the issue related to the protection of those entitled to a reserved share of the estate. As far as unity is concerned in Italy it is thought that regardless of the nature of estate, one law should apply. Italian law of private international law (ILPIL) art 46(1) states that the law of the country of the nationality of the deceased at the time of death governs the whole succession. This is a traditional principle. Under the Regulation the principle of unity is not absolute. The threat lies with renvoi. Art 13(1) of ILPIL provides for renvoi similar to art 34 of Regulation. In Italian case law renvoi is now almost non-existent. Renvoi does not operate when party autonomy is applicable. The Succession Regulation uses habitual residence as the connecting factor for jurisdiction and applicable law. With regards to choice of law, Art 57 of the Regulation provides opportunity of jurisdiction as a consequence of a choice of law. In art 46 of ILPIL uses nationality of deceased for applicable law and a variety of jurisdiction options. Concern was raised over the plurality of heads of jurisdiction in that Italian courts may find themselves competent even when there is a weak connection for succession. The succession could be considered in its entire terms even when the assets are outside of Italy such as in cases where nationality is the connecting factor and there are no assets within Italy. Contrary to art 12 of the Regulation, there is no course for Italy to dismiss a claim in view of the fact that the judgment may not be effective where the goods are situated. Party autonomy is a key principle of the Succession Regulation. Which is not surprising. Art 46(2) ILPIL there is a role for party autonomy. To compare this article with art 22 of the Regulation there is one point which is markedly different the choice in art 46(2) will not be effective if at the moment of death the person was not resident in the state. This is a problem where needs of reserving the assets. The approach is a cautious one. The approach in art 22 of the Regulation is different in that the person may choose as the law to govern his succession the law of his nationality at the time of making his choice or at the time of death. PA is favoured by the regulation as agreement to succession. This is not mentioned in ILPIL. It should be noted that under ILPIL the general agreement for succession, there is now the possibility to enter into an agreement ensure the passing of whole or parts of business to family members at the time of death without having problems arising from reserved share. The protection of those entitled to a reserved share of the estate. The art 46(2) of ILPIL states that for Italian nationals that choice of law should not affect the reserved share of the estate providing that the deceased was resident in the state at the time of death. This is a highly controversial provision as it is considered discriminatory. Nothing like this exists in the Regulation. However it is culturally important for Italy both for family and economic reasons. The rules surrounding the reserved portion do not fall within Italian public policy. The response from the room was that art 46(2) had to go. Part IV SPECIALIST TOPICS: DO THEY NEED A SPECIALISED REGIME? a. Private International Law Aspects of Collective Redress Consumers are able to represent themselves or a group can represent them. The most difficult step to be passed by the claimants is for the claim for the class action to be accepted before the court. However it should be easier for them now as last year saw a change in the rules so that the claimants don’t have to prove that their claims are identical, just homogenous. The law does not provide for jurisdiction. Italy has set up commercial law courts, which deal with these cases. These specialised courts are important. There should be one for each region, however not all regions have one, and then the claimant has to go to another one. It is an opt-in system where consumers have to prove that there is homogonous interest to allow the court to deal with the case. The statistics for the number of cases dealing with collective redress appear to vary. There would appear to have been about twenty. Most of them involve banks as the defendants. There has been one anti trust case, which is currently waiting a decision. The General Court has stayed the case until the anti-trust authority has dealt with it, although their decision is not binding on the court. However the important issues for class actions have been unfair commercial practice and private enforcement. Out of twenty cases, the court admitted only four. The admissibility test is the major obstacle in class actions. It was noted that English case law has raised interesting questions concerning jurisdiction. The English courts have said that even where there is no English company directly sanctioned by the European Commission involved in the cartel, if the companies abroad have the same financial identity they can be sued for the purposes of art 2. In the case of E&I the parties were not the same, the defendants were not the same in Italy as the UK, so lis pendens could not apply. The courts then looked at art 28 and accepted that the parties were connected, but nevertheless made the decision that the courts would take too long to make a decision in Italy and made the decision themselves. To say that the Italian courts are slow is obviously controversial in the context of mutual trust. The Milan court also decided on art 5(3) and 6(1). They said that there was a claim for declaratory relief that there was no infringement of competition law and that there are no damages to be restored. They said they couldn’t apply art 5(3) as the damages were in different jurisdictions and as the damages were differentiated damages art 6(1) could not be applied. This decision has been appealed. It was suggested that art 6(1) should have been applicable. Questions were raised as to whether jurisdiction should be covered by legislation. The general view was that it shouldn’t. Forum shopping was a concern, but it was asserted that wealthy defendants would always pay the costs to bring the cases in the jurisdiction that suited them. It was also held that it was good for business in London, as it was perceived as having good judges. A request was made to invite academics from the Netherlands whose efficient courts deal with a high number of cross border cases. It was felt that it would be beneficial to research this area further. b. Private International Law Aspects of Intellectual Property The starting point was that the Italian case law was poor in this area. The courts give a strict interpretation of competence in IP matters. They usually give themselves competence where national patents are concerned but not where foreign patents are involved. This is due to a number of different principles, the application of GAT doctrine and self-restraint in negative declaration claims. Case law was considered with five issues in mind; the application of the GAT Principle, the competence of limited declaration, the place of the harmful event, copyright and the provisional jurisdiction. The GAT principle states that when dealing with foreign cases the court that is competent to hear the case is the court of the state where the patent was registered. This is easy and plain to understand. Before the GAT principle the case law was uncertain. Article 22(4) of Brussels Regulation was not an obstacle to a court in a tort case declaring itself competent. After GAT the case law is uniform and well adjusted. The court does not have jurisdiction when validity is raised. Competence on limited declaration. These cases are the typical case. The claimant seeks a declaration of non-infringement on foreign patent and if the case is brought in forum of domicile, which is rare, the court will assist without problems. The problems arise when it is brought under art 5(3) of the Brussels Convention. The case law was consistent that there was no jurisdiction and a literal interpretation was given, that where the harmful event occurred, that the damage must exist prior to the claim. But when the Brussels Regulation came in there was different wording, the courts denied jurisdiction drawing the distinction between future possible events from the place where no event occurred at all. The second problem was the issue of forum shopping under art 5(3) Brussels Regulation. Place of harmful event in patent cases – how do we work it out to get the real connection. The ECJ does not provide any explanation as to what a real connection is. Traditional ILPIP sticks to territoriality. There can only be a violation of IP right only where it is protected. However, the courts try to never argue against territoriality. Instead they try to work out where the centre of the case lies. In patent cases this might be where the work is put on the market or ‘commercialised’. But this can be interpreted in different ways. For example it can be interpreted as where the goods are sold or advertised or where the parties enter into competition. Case law has shown the place of the harmful event can be where the goods are advertised via the Internet in Italy. In copyright cases the place of harmful event can be broader. The application is wider. Violation of copyright through the Internet is interesting. A case involved an Italian television company against Google and YouTube involving uploading of TV show. Italian courts did not have jurisdiction as the server was in US. However the Italian courts said the place of uploading was only potentially harmful – the place of harm was where it affected the market so the damage was where the harm occurred which was Italy and therefore the Italian courts had jurisdiction. Provisional jurisdiction is famous in places for the possibility to issue cross border measures. There is one case for article 31 which concerned a previous agreement for transfer of patent rights between Austrian and Italian Companies. Due to the failure to comply with the agreement the Austrian party revoked the patent in Austria. The Italian company put in a claim in the Italian courts to prevent an injunction preventing the use of the patent in Italy. The competent court in the agreement was the Austrian court. However the Italian court found that article 31 gave them jurisdiction but that it should be heard in Rome and not Turin where it was registered and that there was no need for protection.