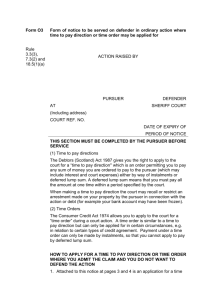

Montgomery v Lanarkshire Health Board

advertisement

MONTGOMERY V LANARKSHIRE HEALTH BOARD Subject: Clinical negligence – consent – duties of health care professionals to discuss treatment options – causation of harm to wrong Summary of Judgment A pursuer whose child suffered serious injury at birth claimed that she ought to have had the option of caesarean section [“CS”] discussed with her as a valid treatment option, as well as vaginal birth. The child’s delivery (vaginally) was impeded as a consequence of shoulder dystocia, resulting in traumatic birth leading to cerebral palsy. The small stature of the mother (who was diabetic) and the large size of the foetus was such that there was an elevated risk of shoulder dystocia, which was not communicated to the mother in clear terms or at all. It was accepted by the Defenders that if a planned CS had taken place, the injury to the child would not have occurred. At proof (viz trial) the Lord Ordinary (Lord Bannatyne) held that medical practice did not require that CS be discussed with the pursuer as the risk was such that it would not have been negligent of the doctor in question to advise of the risks of vaginal birth, and thus was under no obligation to discuss CS with the patient. Further, he held that had the pursuer been offered a CS, she would probably not have accepted it. On Appeal to the Inner House of the Court of Session, the Appeal was refused and the judgment of the Lord Ordinary adhered to. Both courts applied the law as stated in Bolitho1 and Sidaway2. The Supreme Court held unanimously (a bench of seven justices) (1) that the option of CS ought to have been discussed with the Pursuer as a treatment option; (2) that the issue of whether it ought to have been discussed with the patient was not one of negligence, but one of patient autonomy and for determination by the courts and the law, not medical practice [para 85]; (3) that (despite the views of the Lord Ordinary on 1 Bolitho v City and Hackney Health Authority [1998] AC 232 Sidaway v The Board of Governors of Bethlem Royal Hospital and Maudsley Hospital [1985] AC 871 2 the evidence) a review of the evidence was such that he (and the Inner House on appeal) had come to an incorrect conclusion; (4) that the true test is in such a case is whether the doctor exercised reasonable care to ensure that the patient is aware of material risks, and alternative treatments, judged by the standard of a reasonable person in the patient’s position would be likely to attach significance to the risk [para 87]; (5) and that the evidence in fact demonstrated that had the option of CS been discussed with the pursuer she would probably have accepted that course of treatment. Accordingly, judgment for the agreed damages (of approximately £5.5m plus approximately £2m in interest) would be pronounced in the pursuer’s favour. Cases of Bolitho and Sidaway3 overruled [para 86]; holding that they no longer reflected modern attitudes to patient centred treatment and failed to give due respect to the ability of patients to understand the treatment options; and resulted in unacceptable medical paternalism. COMMENT: One can argue whether this case is the most important clinical negligence claim in 30 or 60 years. But what can be said is that it causes a profound and fundamental change in the rights of patients; and in the grounds upon which litigation can be conducted. The fact that the case emanated from Scotland makes no difference to its effect throughout the United Kingdom. Indeed, lead counsel for the appellant was of the English Bar. The GMC intervened represented by Andrew Smith QC, Compass Chambers, in essence supporting the Appellant’s position. The following points are critical to the decision. 1. The issue of what should be discussed with a patient is a matter of law, not professional practice. In Scotland, the equivalent of Bolam is contained in the 3 Sidaway v The Board of Governors of Bethlem Royal Hospital and Maudsley Hospital [1985] AC 871 case of Hunter v Hanley4 (which is in fact relied upon in Bolam5). In pleading a case of lack of consent, it is therefore not a matter for expert opinion from Doctors of the medical profession. It is for the courts and the law to determine, and not doctors. Thus, if there is a failure to obtain consent, that is a matter of fact for the trier of fact and not for expert evidence. 2. The obligation of a doctor to discuss treatment options is largely determined by the views of what a reasonable patient might wish to know. But that objective test is tempered by the requirement that if a patient asks for information it should not be withheld from him (by the adoption of the reasoning in Rogers v Whittaker from the Australian courts). 3. The only exception to the requirement to provide information is rare and is the therapeutic exception: that to tell the patient the true position would be positively harmful to his or her health and welfare. 4. The obligation is not discharged by barraging the patient with statistics about risks. Neither is it discharged by obtaining a signature on a consent form [see paragraph 89]. Doctors will have to take much care now (as is in fact a requirement of GMC guidance) to take clear and careful notes. 5. Although the views of a trier of fact are usually more or less sacrosanct, in this particular case the Lord Ordinary failed to have due regard to the evidence as a whole. He failed to record that the allegedly negligent doctor had stated that if CS was offered to women they would usually accept it. Thus the evidence from all witnesses was that had the option been offered it would probably have been accepted. The Supreme Court therefore felt entitled to revisit the issue and specifically reserved their views on whether Chester v Afshar6 was correctly decided. An interesting issue of practice now arises in proof of lack of consent. I simply offer as a suggestion how matters may progress in Scotland. The decision is in essence retrospective. In concluding that Sidaway and Bolitho are wrong, despite the fact that this change in the law is based upon modern attitudes to patient care, the decision of the Supreme Court adopts the legal fiction of stating what 4 1955 SC 200 Bolam v Friern Hospital Management [1957] 1 WLR 582 6 [2005] 1 AC 134 5 the law always was. Reference is made in the judgment to the GMC guidance in 2008 for the decision; and of course Sam Montgomery was born in October 1999. GMC guidance dates from as early as 1995. There is therefore a powerful argument that cases going back many decades will be capable of litigation – provided there are no time bar or prescription issues. However, there are undoubtedly strong arguments as to why limitation or time bar will not apply (such as only now knowing that a claim is sound, or that the injured party had no capacity to sue until the present time). I ask this question: if a pursuer litigated years ago and lost on a negligence argument, why can they not now re litigate? The issue of consent was not decided and therefore arguably there was nothing that was res judicata. Solicitors might wish to reconsider the lost cases of decades ago…. The GMC’s submissions were to the effect that their guidance (going back to 1995) simply reflected the position in law and practice and was not a new rule that had to be complied with. Practitioners who represent pursuers should therefore rely upon the GMC guidance as the foundation of their claims in this area and probably the submissions put in by the GMC to the Supreme Court. (I am sure GMC Legal will provide them if requested failing which I can try to assist. These are in relatively wide circulation, and have been lodged as productions in a few cases already). It is suggested that the most important factual issues are: was the patient engaged in a discussion about treatment options in a way that they could understand? [see GMC guidance on this] If not, then had they been advised of the treatment options and risks, would they have opted for a different treatment or no treatment? And if they had adopted that alternative course, would the injury have occurred anyway? All this has to be clear in witness statements and the final point in an expert report. Even if the treatment would still have taken place, it may be that a Chester v Afshar approach could be successful although causation of damage would still be an issue. Much debate has been had on whether a small risk of slight damage has to be discussed. That is not in fact resolved, and I suggest that one will know a negligent failure when it presents itself. Equally if the risk was slight of tiny injury, is it realistic that such would be litigated at all? Both the medical and legal professions will face challenges as to exactly how this case will change practices. But past misdemeanours will be ripe for litigation now. As was observed in the principal judgment, if a patient truly consents in the full knowledge of risks, it is highly unlikely that they will be able to complain if the risk in fact manifests. That patients can then ‘own’ the decision with the attendant risks is a factor to reduce, not increase, litigation. This case is one which is classically what the Supreme Court was designed to do: to bring the law up to date with social expectation. I suspect that defenders will have a difficult job in defending lack of consent litigation now as it is clear that doctors did not follow a practice that they ought to have followed. The old defence of “it was not common or universal practice to advise of these risks” now helps rather than hinders pursuers. One final thought. In the many cerebral palsy cases I have been involved in, a regular issue arising is interpretation of the CTG traces. Once pathological, the protocols demanded that intervention be effected quickly. However, if merely “suspicious” that was enough to allow a “wait and see” approach. The debate often centred upon whether the tracing – usually of poor quality and hard to interpret – was pathological or suspicious. Defenders were able to avoid liability by bringing in a doctor who might say: “Well I don’t think it is pathological. I would therefore have waited to see how it developed”. In the light of Montgomery, that Doctor would be under a duty to discuss the options with the patient. “We can wait and see if it gets worse or better, but I have to tell you your baby is struggling a bit. This is not a normal trace. If you wish we can start taking steps to a caesarean now, or you can take the risk.” Without such a conversation, in my view the Montgomery case gives rise to liability by the doctors. Andrew Smith QC Advocate and Barrister, Compass Chambers, Scotland Crown Office Chambers, London