Core writing assignment 2-2

advertisement

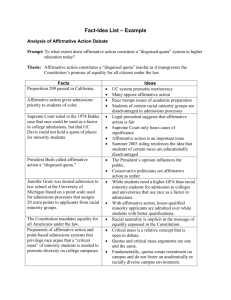

Running Head: APPLICANT POOLS. 1 Applicant Pool Discrimination: How Minorities are Viewed Differently in the College Application Process. Camden E. Dechert Virginia Commonwealth University APPLICANT POOLS. Racial stereotyping and profiling is a prevalent factor in today’s world, yet it is a topic that most people would prefer to avoid. With the increasing pressure to get an education and the selectiveness of American colleges, students are finding it even harder to secure acceptances at their top choices; especially those that fall out of the majority. Copious qualifications are strung throughout the college application process and will racism still existing today it often appears that under-qualified students are granted spots at elite schools simply because of the color of their skin. In addition, the college application process segregates minorities between those that are privileged, i.e. Caucasians and Asian Americans, and those who are underprivileged, i.e. American Indian, Black or African American, Hispanic or Latino, and Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander. This perception does not fall short of the application process though; the correlation between race and income is one that much of the population fails to consciously realize they perceive. Thus, this facet is consistently swept under the rug and financial status is constantly considered a non-contender for applicants; however, it appears that it is deliberately studied. It seems fair for universities to reserve spots for particular races to ensure a level of diversity; yet, the favoring of those who suffer from discrimination is unfair to very qualified students who may not be considered because they are not a minority. According to the CDC (2015), approximately 36.3% of the population is considered a minority. The United States is a melting pot for diversity, including American Indian, Asian American, Black or African American, Hispanic or Latino, and Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander (Racial & Ethnic Minority Populations, para. 1). In order for a college or university to attract a diverse student body, they must appeal to all races, ethnicities, genders, etc. Many colleges implement the process called “Affirmative Action,” where they exhibit special preference to applicants that suffer from discrimination. 2 APPLICANT POOLS. 3 Thus, the question emerges as to whether it is wrong to racially stereotype students in the college admission process? Furthermore, why are college applicants that are minorities more likely to be accepted, and what are the implications of the affirmative action process? The consequences of racial stereotyping and favoritism are explored through McCauley’s “Are stereotypes exaggerated? A sampling of racial, gender, academic, occupational, and political stereotypes,” Silver’s “Why It's OK for Colleges to Accept Minorities With Lower SAT Scores,” PérezPeña’s “To Enroll More Minority Students, Colleges Work Around the Courts,” Espenshade’s “No longer separate, not yet equal: Race and class in elite college admission and campus life,” Francis and Tannuri- Pianto’s “The Redistributive Equity of Affirmative Action: Exploring the Role of Race, Socioeconomic Status, and Gender in College” and along with data from the CDC, an ethical and conclusive result must arise. First, evaluation of the consequences and perspectives of minority students applying to America’s top colleges is imperative. Secondly, the general population must understand how the fairness in education applies to the United State’s work force. According to McCauley (1995), some occupations are predominantly held by particular genders, as occupations are heavily gender and race stereotyped. Additionally, certain jobs may be stereotyped as being held by certain races. This, however, can be exaggerated. McCauley (1995) stresses that these “simple pictures in our heads save us from the complexity of the world outside” (p. 238). Similarly, colleges can show tendencies to accept minorities over Caucasians, even when they may not be as qualified. Most jobs require some form of completed education, so if minorities were not granted secured spots in colleges they might have trouble finding jobs. Francis and TannuriPianto (2012) note that “even though the rate of ethnic intermarriage has remained relatively high, significant racial disparities in education… continue to exist” (para. 1). Regarding this APPLICANT POOLS. 4 standard, several different universities have begun to adopt “racial quotas” for admissions. In 2004, the University of Brasilia reserved 20% of available admissions slots for students who self-identified as Negro, or black which is a considerable amount of the admitting class (Francis, Tannuri-Pianto, 2012, para. 2). Of the 20% admitted, not all were as qualified as the rejected students who did not identify Negro or black. Furthermore, the University also factored income into the 20% of black students admitted, which precedes the stereotype that minorities are not as financially stable as non-minority students. The persistence of racial inequality notably exists; Francis and Tannuri-Pianto (2012) touch on the prevalence in their assertion that “a number of universities have policies targeted to the underprivileged and a few… to blacks specifically” (para. 4). Thomas Espenshade states that colleges do this by targeting minority high schools using recruitment officers who are also minorities. Furthermore, Silver (2012) highlights that affirmative action when selecting students “operates under the assumption that minorities either do not value SAT prep of cannot afford it” (para. 5). Although she believes this statement to be false and only circumstantial, she asserts that it “adequately compensates… for the fact that some minorities may not have the same preparation opportunities as other applicants” (Silver, 2012, para. 6-7). In order to accurately answer the question at hand, we must also determine the benefits of affirmative action and the consequences of eliminating it. Racial quotas appear unfair, yet Tannuri-Pianto and Francis (2012) point out that black students selected for admission at the University of Brasilia “are required to attend an interview with a university panel to verify they are ‘black enough’ to qualify” (para. 11). The verifications include “lectures and events on the value of blacks in society, academic tutoring programs, and a permanent space on campus to study, meet, and have cultural activities” (Francis, Tannuri-Pianto, 2012, para. 11). While APPLICANT POOLS. 5 Espenshade realizes that this process is controversial, he also evaluates the consequences if race were not considered. He exclaims, “minority students may have a lower tendency to apply to an institution that no longer appears as committed to attracting a diverse student body” (Espenshade, 2009, p. 34). He also poses the possibility that colleges could continue to racially stereotype minorities without explicitly using affirmative action. Additionally, Espenshade predicts that if racial favoritism were to be banned or eliminated, acceptance rates for minorities would dramatically decrease. Furthermore, he cites Justice Sandra Day O’Connor’s words that “if the number of underrepresented minority students at these selective colleges and universities were to become so small,” they would no longer serve as social pathways for leadership (Espenshade, 2009, p. 345). The most striking effect on admissions that Espenshade points out pertains to Caucasians and asian applicants. If every student were to be considered with no regard to race, acceptance rates for white students would fall by three percent and acceptance rates for Asians would increase by fifteen percent. Although this would dramatically skew the diversity of students at universities, it would increase the fairness of the college application process (Espenshade, 2009, p. 346), along with increasing the overall value of knowledge in the United States. Our Country is one that thrives off of competition, the destruction of racial consideration would in turn increase competitiveness amongst every race to ultimately achieve higher knowledge rather than relying on aspects such as race or gender. In a New York Times article, affirmative action is shown as “open to interpretation” by college admissions deans. Pérez- Peña (2012) quotes that “even if the supreme court limits the options, colleges and universities will be seeking diversity by any means possible” (para. 6). He also asserts that this leads to obvious stereotyping that minorities aren't as academically qualified APPLICANT POOLS. 6 as Caucasians, and while this can be the case, it is an unfair generalization (Pérez- Peña , 2012, para. 5-7). For example, a school in Texas “admits the top students at every high school in the state, but also admits additional students with a system that takes race into account” (PérezPeña, 2012, para. 10). While university officials “insist that their systems are race-blind,” it appears that many colleges give special consideration to minorities to regulate ratios for the “what-ifs” (Pérez- Peña, 2012, para. 25). The stance on affirmative action varies from author to author, yet all seem to come to the same consensus that the help it gives to minorities is explicitly notable. Silver argues that it is perfectly fine to accept less qualified students since they are under privileged and misrepresented; in contrast, Espenshade notes that it is simply unfair. He points out that the elimination of affirmative action could be catastrophic, while Francis and Tannuri-Pianto’s postulation suggests that racial quotas are a ubiquitous force in acceptance decisions. Ultimately, the implementation and usage of racial quotas are both positive and negative. They are very supportive of minorities and can influence students to be more successful while making further education more attractive. However, the quotas give minorities leverage over non-minority students, which impedes on the fairness of the application process as a whole. Essentially, affirmative action can be both favorable and unacceptable for students, as stated by both Francis and Tannuri-Pianto and Pérez- Peña, who both write about the several different perspectives. Although the usage and elimination of affirmative action has varying consequences, the main focus of American colleges should be to further the education of young people wholesomely. Regardless, it does not appear that every person can be satisfied in such a situation. Thus, in conclusion, it appears that a definite answer to a question of ethics is impossible. APPLICANT POOLS. 7 References Are stereotypes exaggerated? A sampling of racial, gender, academic, occupational, and political stereotypes. McCauley, Clark R. Lee, Yueh-Ting (Ed); Jussim, Lee J. (Ed); McCauley, Clark R. (Ed), (1995). Stereotype accuracy: Toward appreciating group differences. (pp.215-243). Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association, xiv, 330 pp. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/10495-009 Espenshade, T., Radford, Alexandria Walton, & Chung, Chang Young. (2009). No longer separate, not yet equal : Race and class in elite college admission and campus life. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. Francis, Andrew M., & Tannuri-Pianto, Maria. (2012). The Redistributive Equity of Affirmative Action: Exploring the Role of Race, Socioeconomic Status, and Gender in College Admissions. Economics of Education Review, 31(1), 45-55. Pérez- Peña, R. (2012, April 1). New York Times. To Enroll More Minority Students, Colleges Work Around the Courts. Retrieved October 14, 2015, from http://www.nytimes.com/ 2012/04/02/us/college-affirmative-action-policies-change-with-laws.html?_r=0 Racial & Ethnic Minority Populations. (2015, August 11). Retrieved October 14, 2015, from http://www.cdc.gov/minorityhealth/populations/remp.html Silver, N. (2012, April 11). Why It's OK for Colleges to Accept Minorities With Lower SAT Scores. Retrieved October 14, 2015, from http://mic.com/articles/6827/why-it-s-ok-forcolleges-to-accept-minorities-with-lower-sat-scores