Pickleweed and Saltgrass

advertisement

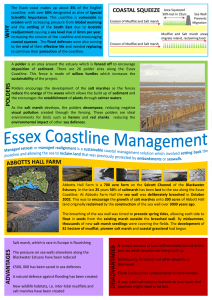

Lawrence Fernandez Bio 25: Ecology of SF Bay Pickleweed & Saltgrass Pickleweed and Saltgrass are neighboring species in the bay area’s salt marshes, an undulating ecotone that once covered about 300 square miles in the bay area. Acting as nature’s sieves, salt marshes occur at the shallow mouths of freshwater streams and rivers as they flow in to the bay, collecting sediment and building more marshland. Though salt marshes are wetland environments, many of the plants in salt marshes share evolutionary characteristics, or are relatives of, those found in desert regions. In both salt marshes and desert regions, lack of access to fresh water is the primary stressor. Salt marshes have the added difficulty of water submergence and low oxygen levels due to water submergence. Because these stressors depend on the presence and duration of submergence in salt water, salt marshes are a unique gradient of ecotones, each level defined by a dominant plant adapted to a particular salinity and oxygen level as determined by the flux of the tides Pickleweed can be found just above the mean high tide level as the second emergent plant, occurring after cordgrass and just before salt grass. It can withstand salinity levels as high as 6%, but cannot withstand the levels of submergence faced by the cordgrass. Pickleweed (Salicornia virginica) is a short, upright plant with a smooth, fleshy cylindrical stem with tiny leaves almost invisible- giving it the appearance of succulent “pickles.” Species of Salicornia are found in marsh systems and deserts around the world, and are more commonly called glasswort, for their historic use in the production of glass. Pickleweed, like other plants in the salt marshes, is a salt-adapted halophyte. Each undulation of the tide deposits more salt water, and salt levels concentrate as water evaporates. To deal with this less than ideal waters source, pickleweed roots pump out salt water with sodium-potassium pumps, and sequesters the rest in vacuoles at the end of its fleshy branches. As the dry season progresses and more and more salts accumulate, the pickleweed abandons the salt-packed leaves, drawing out chlorophyll and leaving behind the bright red segments to fall back to the earth. Pickleweed relies on the wind to carry pollen from a male plant to a female plant, and relies on the water to carry its seeds. Its flowers are inconspicuous and yellow, blooming from august to november. It produces an abundance of tiny, hair covered seeds. The seeds float on the high tide, which carries them out to new locations. Saltgrass (Distichlis spicata) is another halophyte, found just above the high tide level in the vegetation band upland from pickleweed, where it is drier. It is a perennial plant, reproducing through both seeding and cloning itself by underground rhizomes. It forms dense mats of vegetation, making it a “first to sow” plant in wetland restoration where soil retention is important. While pickleweed sequesters salt, saltgrass excretes it. Its slender, blue-gray leaves glitter with excreted salt crystals before the tide washes it away. Both pickleweed and saltgrass provide important habitat and food source for the creatures of the salt marshes. Pickleweed, occurring in dense, miniature forests, provide structure and habitat for nesting shore birds such as the savannah sparrow, as well as forage and food opportunities for small mammals, ducks, birds, and insects. The wandering skipper butterfly relies solely on saltgrass as its host plant. While the salty greenery of both the pickleweed and salt grass require special adaptation- or seasonality- to be palatable to most species, the abundant seeds are much sought after food source in the salt marsh ecosystem. If you go foraging in the early spring, the tender green tips can be harvested for use in salads and pickles. Or, if you’ve got more money than time, you can buy it for around $5 dollars a pound at various farmers’ and specialty markets in the bay area. A nicety in the human diet, Pickleweed is a staple for another bay area resident, the salt marsh harvest mouse. This thumb sized, endangered mouse is a salt marsh specialist, having evolved the ability to live on salt water and saline vegetation such as the pickleweed. Further, the structural support of pickleweed is important in providing this tiny, delicious mammal protection from predatory shore birds and mammals. During the highest of high tides when even the pickleweed is covered in water, the salt marsh harvest mouse will swim its way upland to hide out the tide in saltgrass, alkali heath, or other salt plants of the coastal strand. Pickleweed and saltgrass are both wonderfully competitive, quick growing early successional species that do well in any salt marsh environment. The dangers they face are the dangers that all salt marsh inhabitant’s face- the destruction, filling, and draining of salt marshes. Further, the introduction of invasive, non-native species can disrupt the distribution of pickleweed and salt grass. Of particular concern is the non-native Spartina that has invaded the bay area, outcompeting pickleweed in the mid-tide zone and pushing it further upland. Spartina and its hybrids with the local species quickly take over marshlands, eliminating the structural and ecological diversity that makes bay area marshlands such distinct, abundant places of life and productivity. Bibliography: 1) Aquarium of the Pacific: Online Learning Center Pickleweed i. http://www.aquariumofpacific.org/onlinelearningcenter/full_descri ption/pickleweed/ Saltgrass i. http://www.aquariumofpacific.org/onlinelearningcenter/full_descri ption/saltgrass 2) Sulivan, Rob,“Native Pickleweed offers a taste of the wild,” SFGate.com, Jan 16th 2008 http://articles.sfgate.com/2008-01-16/home-andgarden/17148934_1_species-plant-succulents 3) Conradson, Diane R. Exploring Our Baylands. San Francisco Wildlife Society, 1996. 4) “Invasive Spartina in Humbolt County” http://www.fws.gov/humboldtbay/spartina.html 5) Schoenherr, Allan. A Natural History of California. University of California Press, 1992