Auditory Processing Disorder: New Zealand

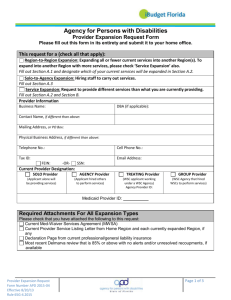

advertisement