tzofit Ofengenden Research Proposa

advertisement

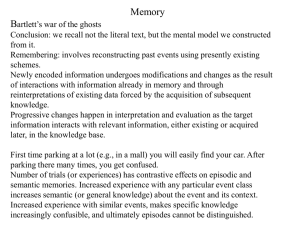

Tzofit Ofengenden Research Statement Neurobiological Paradigm of Memory Formation and its Theoretical and Ethical Implications My research interests lie in neurophilosophy and neuroethics, a new interdisciplinary field in bioethics. I am interested in the way neuroscience reformulates and reshapes central philosophical concepts such as memory, imagination, and consciousness as well as the possibilities these paradigms open for brain interventions and the ethical implications that arise from these new conceptualizations. In my future research, I plan to investigate neuroscientific theories of memory and their theoretical and ethical implications. I will examine whether neurobiological theory of memory destabilizes the notion of memory as a source of factual truth and thus undermines the notion of personal identity, concept of self, whether there are consequences in legal cases and the ethical implications of intervention and memory manipulation. Memory is perceived as a source of knowledge, a reliable reference to our past. Our belief is that memories in general are trustworthy, that a remembered event probably took place. The trust that we put in our memories has important ethical implications. We rely on the truth of our memories to form authentic personal identity, to give testimony at courts, and to create trustworthy personal takes of historical events. When memory exhibits forgetfulness, errors, or inaccuracy, it is perceived as dysfunction, deficiency, and failure. In cases when memory consistently fails to refer to reality of the past, it is treated as a pathological amnesia. The malfunctions of memory are frequently considered in relation with the Constructive Memory Framework (CMF). CMF deals with types of memory distortions or occasions in which our memory fails to reproduce reality. Examples of these distortions include false recognition, confabulation, bias, misattribution, error, illusion, and suggestibility.1 As a consequence, theoretical and empirical investigations have examined in detail the relation between memory and truthfulness. However, while CMF emphasizes the accuracy-inaccuracy of memories, neurobiological accounts of memory formation examine the underlying neural mechanisms of memory and emphasize the dynamic process of memory adjustment.2 In the past, researchers claimed that memory consolidation, the process of memory stabilization, takes place only once. According to such accounts, a new memory is initially labile and becomes stabilized over time through the process of consolidation. This process converts an unstable Daniel L. Schachter, Kenneth A. Norman and Wilme Koutstaal, “The Cognitive Neuroscience of Constructive Memory”, Annual Review of Psychology, vol 49,(1998): 289 -318. 2 The claim is not that there are contradictions between the various scientific manifestations, but rather the opposite, that the psychological conceptualization of constructive memory functions correlates with and is realized in the neurobiological theory of memory formation. However, a coherent and unified theory of memory that encompasses the multiple scientific levels has not yet been established. 1 1 short-term memory into a stable long-term memory. It was believed that after consolidation, memories are stable and resilient to disruption. 3 However, currently neuroscientists who focus on neural processes and mechanisms of memory persistence (synaptic strength and plasticity) show that consolidation takes place not only after new learning (encoding), but also after every recall (memory retrieval). During retrieval, consolidated memories enter a transient state where they become labile once again, and require another phase of consolidation (known as “reconsolidation”) in order to persist. 4 Thus, reconsolidation theory claims that a memory is not a literal reproduction of the past, but instead an ongoing constructive process. Memory traces are modified and reconstructed repeatedly. The current hypothesis assumes that the labile phase of reconsolidation allows new information to be associated with established and reactivated memories.5 Memory traces are modified and reconstructed to update and adjust them to new circumstances. 6 Every time we recall, new perceptions, expectations, attitudes, perspectives are fused into the original memory trace, thereby constructing a new memory, a new meaning.7 Reconsolidation is a natural process where the memory trace of an event undergoes various modifications. These modifications should not be considered errors or fabrication, but rather should be taken as normal brain activity. Memory distortion is characteristic of normal rather than pathological or abnormal remembering. Thus, this neurobiological theory of memory provides a new framework for rethinking memory. If it is true that stored memories are continually being revived and revised through normal brain activity, this finding destabilizes the notion that memory is a source of factual truth and also challenges the way we understand memory and remembering. This new theory poses new problems and raises several questions. What is the exact epistemological status of memories? How does this neurobiological model of memory impact the way in which we conceive of and relate to our past and to reality? Can we still speak about truthful memories even if they are in a perpetual state of modification? If our memories are perpetually modified, does this not imply that they are essentially memories of memories and reremembering of remembering rather than memories of the original perceived experience? This new paradigm raises further questions that deal with prevailing misconceptions of memory. Although it has been several decades since researchers have uncovered the dynamic character of memory, and the view that memory is reconstructive is not new, 8 the prevailing idea is that Alberini CM, “Mechanisms of Memory Stabilization: Are Consolidation and Reconsolidation Similar or Distinct Processes?”, Trends Neurosci 28, (2005): 51. 4 Dudai, Yadin, “The Neurobiology of Consolidations, Or, How stable is the Engram?” Ann. Rev. Psychol., 55, (2004): 51-86. See also Alberini CM, “Mechanisms of Memory stabilization: Are Consolidation and Reconsolidation Similar or Distinct Processes?”, 51. 5 Tronel S, Milekic MH, Alberine CM, ”Linking New information to a Reactivated memory Requires Consolidation but not reconsolidation Mechanism”, PloS Biol., 3(2005): 1630. 6 Dudai, “Reconsolidation: the Advantage of Being Refocused”, 175. 7 Dudai, Yadin, “The Neurobiology of Consolidation, Or, How Stable is the Engram?”, 51-86. See also Steven, Rose, The Making of memory, From Molecules to Mind, (London: Vintage, 2003), 2. 8 Bartlett introduces the idea that memory is a reconstructive process. See, Bartlett, F., C., Remembering: A Study in Experimental and Social Psychology, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1932), and Neisser Ulrich, Cognitive Psychology, (New York: Appleton Century Crofts, 1976). 3 2 memories are stored changelessly and permanently and that remembering is accurate.9 What is the reason for this discrepancy between the neuroscientific view of the reconstructive nature of memory and the layman’s spontaneous conception of memory as an accurate representation of the past? Are we deluded by a wrong concept of memory? If the answer is yes, another question follows — does a belief that accompanies our memories deceive us or does having a false concept of memory and remembering misleads us? It might be that readjustment or memory persistence itself is responsible for this faulty belief. Readjustment takes place without conscious awareness as it reorganizes our memory coherently and leaves us with the feeling that the representation is faithful and accurate. The current neuroscientific account of memory not only undermines previous concepts but casts doubts on the authority of memories. Memory modification is a natural process of a normal brain activity. Thus, the conception of memory as a reliable source of the past is challenged. This understanding has theoretical and ethical implications as well. It changes our self-perception and raises questions regarding our illusion of constant memories and persistent sense of self. Autobiographical memories function to form personal identity and concept of self.10 It is the only type of memory which provides an epistemic authority on our own past. Yet do neuroscientific theories of memory challenge this authority? Present neuronal processes modify memories of the past over and over again without us being aware that our memories differ from real past occurrences. Memories persist but are different from the way they originally were when first generated. Challenging memory as a reliable source of knowledge has crucial consequences in legal cases.11 Relying on modified memories which are not necessary false but does not reflect the past accurately might have devastating consequences in cases such as conviction of innocent people or releasing guilty ones. The importance of the neurobiological theory of memory is not limited to the above-mentioned theoretical and ethical implications. This paradigm of memory formation also guides the development of new drugs and behavioral methods which alter specific autobiographical memories. These treatments might be used to erase unwanted memories or enhance desired ones. Thus, understanding the neurobiological paradigm will enable us to consider how and in what way memory manipulations extend natural memory processes or whether they disturb these processes. The research is divided to two parts. In the first part, I will review how neuroscientific theories of memory describe the way in which memories are established and maintained in the brain. I will review the functions and neurological basis of memory, and the varieties, forms, and conditions of forgetting, misremembering, and memory distortions. Since I deal here only with memory as a normal state, I do not deal with memory disorders, the states where memory goes Daniel Wright and Elizabeth Loftus, “Eyewitness Memory”, in Memory in the Real World, ed: Gillian Cohen and Martin Conway, (New York: Psychology Press, 2008), 93. See also, Benton, T. R., Ross, D. F., Bradshaw, E., Thomas, W. N., & Bradshaw G. S., “Eyewitness Memory is still Not Common Sense: Comparing Judges and Law Enforcement to Eyewitness Experts”, Applied Cognitive Psychology 20, (2006): 115-129. 9 Cohen, Gillian, “The Study of Everyday Memory”, in Memory in the Real World, ed: Gillian Cohen and Martin Cohen, (New York: Psychology press, 2008), 1. 11 Daniel Wright and Elizabeth Loftus, “Eyewitness Memory”, in Memory in the Real World, 91-105. 10 3 wrong due to age related memory loss, Alzheimer disease, or brain injuries. In the first part, I also examine whether the neuroscientific theories of memory formation challenge the prevailing concepts of memory and whether a new, more correct concept has to be established. In the second part, I deal with the ethical implications that derive from current theories of memory, whether these theories challenge the authority of memory as a reliable source of our past knowledge and our sense of personal identity. I will also deal with whether intervention and memory manipulation have the same nature as natural unconscious modifications that take place constantly. 4