A Short History of the Phinizy Swamp Area

advertisement

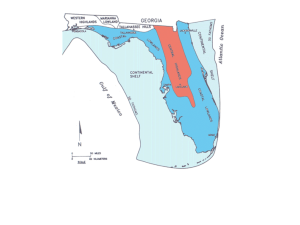

1 The Naming and the Use of Phinizy Swamp, Georgia By Abe Wilson The Savannah River’s edges have been settled area for at least the last ten thousand years. Archeological sites around the central Savannah River area date back to the Paleo-Indian period of the earliest type. By 8000 B.C.E., the environment was approaching what is found today in this area.1 Phinizy Swamp has been settled at least since the Early Archaic period with radio carbon dating of the Phinizy Swamp archaeological dig placing the age of its fires at 7110 B.C.E.2 Though an early date, this is at least a couple of hundred years later than the evidence from some of the lithic artifacts. Stone arrowheads in particular demonstrate an earlier date and long period of settlement.3 The time of most intense usage appears to have been in the Middle Archaic to Late Archaic periods which is often described in the literature as MALA and lasting in the Phinizy Swamp for seven hundred years.4 The sites, along with sites from Taylor Hill, and later research from Butler Creek drainage to the south of Phinizy Swamp demonstrate the continuous use of these sites over the time of occupation. Land usage changed at the end of the Archaic period but was stable within. The Phinizy Swamp archaeological site also offered an anomaly for the time and place of occupation in clay coverings found near the cooking pits. It appears that the clay was used to line 1 Renee Lewis, et al. Integrated Cultural Resource Management Plan For Fort Gordon, Georgia. Atlanta GA: Fort Gordon Environmental Division / Natural Resources Branch, 2011: 32. 2 Daniel T. Elliott, et al. “Data Recovery at Lovers Lane, Phinizy Swamp and the Old Dikes Sites Bobby Jones Expressway Extension Corridor Augusta, Georgia” Occasional Papers in Cultural Resource Management #7. Athens, GA: Southeastern Archeological Services, Inc. (January 1994): 160. 3 Elliott, “Lovers Lane” : 161. 4 Daniel T. Elliott, “Archaic of the Savannah River: A History of Research from 1773 to 1993” LAMAR Institute Publication Series, Report Number 109 (2006): 10. 2 the walls of the cooking pits possibly to better utilize the heat of the fire.5 Archeological digs in and around Phinizy Swamp also demonstrated other innovations of the settlers as well. These were the first non-shell based technologies in the area. Though sharing other cultural traits similar to their neighbors, the settlers of the area in and around Phinizy Swamp did not exploit shell animals to the degree of their coastal neighbors as a food and for tools.6 Since shell can be shaped as easily as stone tools and were available along the rivers edge, this has been a surprising discovery. 5 Thomas Whitley and Sudha A. Shah. “An Overview and Analysis of the Middle Archaic in Georgia.” Occasional Papers in Cultural Resource Management #16. Brockington and Associates, Inc., (September 2009): 41. 6 Elliot, “Archaic” : 7. 3 Phinizy Swamp and Surrounding Area7 At the end of the Archaic period, around 1,000 B.C.E. ceramics were adopted and soapstone cookwares, as found in the Pig Pen site north of Phinizy Swamp were abandoned or significantly changed in utilization.8 Around 1,550 B.C.E. the central Savannah River riverine sites were abandoned and there was an increase in the use of upland locations for residence and a divergence in material cultures.9 These changes in the place of residence and the types of tools used, indicate a major shift in cultural as well. This era is known as the Woodland Period and is subdivided into Early, Middle and Late like most other eras in Archeology and based upon differences in the shapes of artifacts over time. Differences in the shape of artifacts can be correlated to the cultures from which they came to show how the culture changed or was replaced by a culture that used different types of tools or differently shaped tools. Changes in lifeways are often reflected in material culture. This is demonstrated by the adoption of ceramic pottery at the Stallings Island site dating to the Late Archaic period. With the adoption of food storage, settlement patterns changed as well. Semi-permanent settlements began to be built up and rotated seasonally. Base camps were built up at the intersection of large river tributaries and more difficult terrains were then utilized as necessary for hunting, fishing, mining and so on. In the Late Archaic and Early Woodland periods as populations were moving 7 Southeastern Natural Sciences Academy, “Proposed Corridor of Savannah River Study” (map), Research, accessed 6 Aug. 2013, http://naturalsciencesacademy.org/aboutus/research/. 8Thomas Gresham and R. Jerald Ledbetter. “The Pig Pen Site: Archaeological Investigations at 9RI158 Richmond County, Georgia.” Occasional Papers in Cultural Resource Management #6. Athens GA: Southeastern Archeological Services, Inc. (December 1988): 111. 9 Lewis, CRM Plan for Ft. Gordon: 42. 4 out of the river’s edges, Phinizy Swamp was used as a hunting ground and for logistical camps, in the case of Taylor Hill, on a part time basis.10 Hopewell Interaction Sphere11 The Early Woodland is most importantly defined by the ability of people to better store foods in ceramics. This led to a decentralization of the populations. It also may have contributed to the participating of populations in a phenomenon known as the Hopewell Interaction Sphere with the local expression known as the Swift Creek Culture. This period stands out because of 10 11 Lewis, CRM Plan for Ft. Gordon: 43. Heironymous Rowe, “Hopewell Interaction Sphere” (map), Wikipedia, accessed 6 August 2013. 5 the intense exchange of goods locally and beyond. Though, there are no specific sites from this period within Phinizy Swamp, they do surround Phinizy Swamp at Savannah River Site, Mill Branch and Fort Gordon and would indicate the use of Phinizy Swamp by these populations. 12 Subsistence was largely through hunting and gathering. The primary animals hunted were the white-tailed deer and local small game. As the bow and arrow did not arrive in the Southeastern part of North America until the end of the Woodland Period; the atlatl, a spear throwing device, the spear itself and blowguns were the tools of hunting.13 Throughout the Woodland Period, the cultures on the east coast took part in the Eastern Agricultural Complex. This is a period of continual improvement in the cultivation of crops for consumption and one of a few examples of independent acquisition of farming in the world.14 Cultigens such as squash and corn were introduced to the area, but based on the amount of cultivated area, were probably not a major source of nutrition during this period. That would change in the next. 12 Lewis, CRM Plan for Ft. Gordon: 47. Jerald T. Milanich, The Archaeology of Precolombian Florida, (Gainesville; University Press of Florida, 1994): 111-41. 14 Bruce D. Smith, and Richard A. Yarnell, "Initial Formation of an Indigenous Crop Complex in Eastern North America at 3800 B.P." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Vol 11, No. 16, (2009): 6561–6566. 13 6 The “Three Sisters” crops of beans, corn and squash15 Between 900 C.E. and 1100 C.E. another cultural break is indicated by a radical change from one type of material remains to another. In the Southeast, Mississippian culture replaced Woodland. Societies north of the Fall Line became stratified like much of the rest of the Mississippian cultures. The Fall Line is a geological change from interior bedrock to coastal geology that commonly has rapid changes in elevation. These have influenced settlement patterns all over the world for humans because they create natural barriers and are a source of motive power when a river crosses them as it does near here in Augusta, Georgia. Chiefdoms emerge during this time as a political force. Large mound complexes began to be built and though still mysterious as to their function, were likely used as platforms upon which the higher classes lived apart from commoners as well as burial mounds for the elite. In the Southeast, this is represented by a large number of similar artifacts and practices called the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex.16 Mound centers such as Hollywood and Irene in South Carolina held 15 United States Mint, “Three Sisters Native American One Dollar Coin, 2009” (image) Wikipedia, accessed 6 August, 2013, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:2009NativeAmericanRev.jpg. 16 Lewis, 53. 7 political control over smaller populations located along river edges in the Central Savannah River Area. With the adoption of larger ceramics during the Mississippian period and the cultivation of the traditional “three sisters” crops of squash, beans and corn; the stores were probably controlled by the elite class for distribution. In the areas around Phinizy Swamp, the Mississippian culture was adopted. South of the Richmond County area, change was slower to come. This may be because of the stability of food supplies along the coast at this time. The Central Savannah River Area17 Around 1300 C.E. political instability struck the Mississippian culture. Mound complexes were abandoned, including Hollywood and Irene, both in South Carolina. The Southeastern Ceremonial Complex motifs in arts, goods and wares diminished and pottery became simpler in 17 Spyder_Monkey, “Central Savannah River Area” (map), Wikipedia, accessed 6 August, 2013, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Central_Savannah_River_Area.svg 8 decoration if not construction. Populations did not decline, but instead disbursed across the region including the Savannah River. Little is known about settlement in the latter part of this period except from ethnographic accounts of Spaniards dealing with the people they called Guale. The Guale were a Mississippean culture living on the coast and islands along the area that is now Georgia. It is possible that the patterns of the lives of the residents of the Savannah River basin, in this area had already been so changed by the effects of European contact that they bore little similarity to the cultures that had come before. The Phinizy Swamp area may even have been depopulated by 1450 C.E. as a political buffer zone between the Ocute and Cofitachequi.18 The Cofitachequi were a Muskogean speaking tribe from the center to coast of South Carolina. The Ocute were a chiefdom from central Georgia, who had political tensions between them. The CSRA was directly between these two groups. Proposed Route of the De Soto Expedition19 18 19 David Anderson quoted in Lewis, CRM Plan for Ft. Gordon, 57. Heironymous Rowe, “Proposed Route of De Soto Expedition” (map), Wikipedia, accessed 6 August 2013. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:DeSoto_Map_Leg_2_HRoe_2008.jpg. 9 Spanish explorer, Hernando De Soto, and his men moving east from the town of Cofaqui to Cofitachequi along the Oconee River could have passed through the area around Phinizy Swamp. According to historian Edward Cashin, De Soto may have crossed the Savannah somewhere near the site of Augusta.20 The natural crossings occurred both north and south of Augusta and so could have been anywhere north or south of Augusta for several miles. De Soto found no villages in this area lending some weight to the argument that the Savannah River was a buffer zone area between competing tribes.21 The migration of Europeans to the American coasts caused great changes and disruptions to native ways of life with the introduction of new trade goods, disease and the importation of European politics.22 By the mid-seventeenth century two tribes controlled most of Georgia; the Cherokees and the Creeks. Englishman James Oglethorpe received permission from the “Trustees for Establishing the Colony of Georgia in America,” an organization of the crown in England, to settle Savannah. He began his settlement in 1733 C.E. as a buffer colony for Charles Town from Native Americans and the Spanish to the south.23 The Indian trade proved a quick source of income that expanded quickly to include the creation of Fort Augusta to compete against South Carolina’s Savannah Town (Fort Moore) Shawnee settlement.24 Chickasaw Indians who crossed the Savannah River to help with construction of the fort were settled downriver on the south side of Phinizy Swamp in New Savannah.25 Fort Augusta fell into disrepair between the years of initial 20 Edward J. Cashin, The Story of Augusta, (Augusta, GA: Richmond County Board of Education, 1980), 4. 21 Lewis, 58. 22 Kenneth Coleman, A History of Georgia 2nd edition (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1991), 9-15. 23 Coleman, 16. 24 Cashin, 10. 25 Cashin, 11. 10 occupancy and the French-Indian Wars demonstrating low tension between settlers and natives at the time. Shortly after the close of the French-Indian Wars 700 representatives of five Indian nations and four royal governors met to negotiate the cession of lands to European settlers in the city of Augusta.26 This resulted, in the following decade, in the cession of lands between the Savannah River and the Ogeechee River. European settlers flocked to the new lands.27 After the Revolutionary War, Augusta became an important city in the South. The new Georgia state government was seated in Savannah, but spent part of each year in Augusta. Settlers moved into the area, soon to be known as Phinizy Swamp, as quickly as anywhere else. Mills and millponds dotted the landscape from the turn of the eighteenth century to the mid 20th century. Because roads were in less repair in Georgia than elsewhere along the eastern seaboard, grist, corn and flour mills worked only locally. Rocky Creek had two mills within the bounds of Phinizy Swamp during the Revolutionary and early National period. Edward Barnard, an early prominent citizen of Augusta built the areas first mill around 1750. It was a grist mill built on Rocky Creek in Phinizy Swamp, and according to local historian, Michael White, “Early maps show that the two fords crossing the creek in that era were at today’s Old Savannah Road and approximately where the Augusta levee is today across the old channel.”28 From the beginning of European settlement in the Augusta area, Phinizy Swamp has played a role in the community. Phinizy Mill was located where Rocky Creek passes under Doug Barnard Parkway. The site of the mill was covered over during construction of the modern highway.29 It was one of three mills on Rocky Creek south of Augusta in the nineteenth century. There were mills on 26 Coleman, 49. Lewis, 59. 28 Michael C. White, Waterways and Water Mills, (Warrenton, GA.: CSRA Press, 1995), 73. 29 White, Waterways, 72. 27 11 Wyld pond and Kendrick pond as well as the more famous Phinizy pond.30 There is a less famous Phinizy mill on Butler Creek to the south and west of Phinizy Swamp, but that is a smaller neighborhood mill on a creek with many neighborhood mills.31 That name and the confusing history of Phinizy farm, mill and pond have obfuscated the history of the name Phinizy Swamp. John Lamar was granted two land tracts shortly after the Revolutionary War. These comprised 1300 acres of what later became known as Phinizy Swamp.32 Just before the turn of the eighteenth century Thomas Glascock purchased 200 acres from John Lamar that eventually turned into the factory where one of Eli Whitney’s first cotton ginning machines was set up to work from water power.33 In spite of a Richmond County 1908 map indicating that a particular pond was the location of Eli Whitney’s first cotton ginning machine, the reality of that particular machine being the first in operation is one of several competing claims. The evidence indicates that the gin never went into effective operation as a ginning business.34 Several years later, Eli Whitney was touring the southern water-powered cotton gins and recommended to his partner, Phineas Miller, “the property be sold as soon as possible for what price it would bring.”35 Whatever happened with the early cotton gin on this site and the reasons for its abandonment, the city acquired it for auction. 30 Charles Jones Jr. and Salem Dutcher. Memorial History of Augusta Georgia. (Spartanburg, SC: Reprint Company Publishers, 1980), 398. 31 Jones and Dutcher, Memorial History, 399. 32 Michael C. White, Historic Milling in Richmond County, Georgia, (Warrenton, GA: CSRA Press, 1998), 32. 33 White, Historic Milling, 32. 34 White, Historic Milling, 33. 35 As related in White, Historic Milling, 35. 12 In 1828, the Richmond County tax collector auctioned off the site for $160.36 The property apparently went through several hands before John Phinizy came to own it in the 1840s or early 1850s. The only confirmation of Phinizy’s property having a mill comes, according to historian Michael C. White, from a right-of-way deed allowing Augusta and Waynesboro Railroad to build across part of his pond.37 The site was sold to Mary Doughty from the estate of John Phinizy in 1900 for the high price $4,717 indicating that a substantial improvement was on the plat.38 The land passed through several more hands, even becoming the Eli Whitney Country Club for a time. In owning the property for fifty years or so, the name of Phinizy became attached to the areas affected by his property as well. The 1908 map of Richmond County lists the surrounding property as Phinizy Swamp. There is also a nearby Phinizy Canal, which is not the same as the current and more substantial Phinizy Canal and Phinizy pond.39 The Augusta Chronicle referred to the Phinizy Swamp with familiarity as a geographic reference for readers, for the first time in 1908, describing work being done to mitigate flooding in Augusta.40 By the time George Summers drew his maps in 1928, by hand, with property lines for the whole county, Savannah River Lumber Company, the John Cason farm and John Anne Thompson farm owned most of the western areas of Rocky Creek with the historically important Phinizy Mill and the remains of the first colonial era mill, built and owned by John Lamar. 41 36 White, Historic Milling, 35. White, Waterways, 73. 38 White, Historic Milling, 37. 39 C. L. Whaley, Map of Richmond County, Ga. (Atlanta, GA: The Hudgins Co., 1908). 40 Augusta Chronicle, “For Flood Protection Surveyors Are Working Party Spent Yesterday in the Phinizy Swamp” 10.28.1908, p. 7 accessed by Galileo at http://gilfinduc.usg.edu/vufind/Search/Home 6.17.2013. 41 George Summers, Maps of Richmond County, no.7 and no.12. 37 13 By the twentieth century, the Phinizy Swamp area had acquired its name. The Phinizy Swamp has been a resource to every group of people residing within or nearby for thousands of years. It has been used for food gathering, hunting, farming, horticulture, and water management in one capacity or another throughout the entire period of human occupation. During both the Revolutionary War, near Butler’s Creek and during Prohibition in the swamp itself, the dense area was used to hide activities from the authorities. During the Archaic period, Taylor Hill was used as a logistical camp from which to exploit the rich natural resources near it. During the turn of the twentieth century the residents had the same idea, building a small town from which to farm the surrounding area until flooded out seventy-five years ago. 42 The rich lowlands of the Phinizy Swamp and surrounding area have been consistently used throughout the whole period of human habitation and are now something to be preserved and protected as well. 42 Charles Thompson, interview by author, 5 June, 2013. 14 Bibliography Primary Sources: Charles Thompson. Interview by author. 5 June, 2013. Articles: Elliott, Daniel T.. “Archaic of the Savannah River: A History of Research from 1773 to 1993” LAMAR Institute Publication Series, Report Number 109 (2006) i-26. Elliott, Daniel T. et al. “Data Recovery at Lovers Lane, Phinizy Swamp and the Old Dikes Sites Bobby Jones Expressway Extension Corridor Augusta, Georgia” Occasional Papers in Cultural Resource Management #7. Athens, GA: Southeastern Archeological Services, Inc. (January 1994):1-209. Gresham, Thomas and R. Jerald Ledbetter. “The Pig Pen Site: Archaeological Investigations at 9RI158 Richmond County, Georgia.” Occasional Papers in Cultural Resource Management #6. Athens GA: Southeastern Archeological Services, Inc. (December 1988):1-158. Robertson, Thomas Heard. “The Colonial Plan of Augusta” The Georgia Historical Quarterly Vol. LXXXVI No. 4 (Winter, 2002) 2-28. Smith, Bruce D. and Richard A. Yarnell. "Initial Formation of an Indigenous Crop Complex in Eastern North America at 3800 B.P." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Vol 11, No. 16 (2009): 6561–6566. Whitley, Thomas and Sudha A. Shah. “An Overview and Analysis of the Middle Archaic in Georgia.” Occasional Papers in Cultural Resource Management #16. Brockington and Associates, Inc., (September 2009):1-122. Books: Cashin, Edward J.. The Story of Augusta. Augusta, GA: Richmond County Board of Education, 1980. 15 Coleman, Kenneth. A History of Georgia: 2nd edition. Athens, GA.: University of Georgia Press, 1991. Crumpton, David Nathan. Richmond County Georgia Land Records. Warrenton, GA: D. N. Crumpton, 2006. Georgia Department of Transportation. Proposed Bobby Jones Expressway Extension Project F117-1(11) Richmond County, Georgia and Aiken County, South Carolina Final Environmental Impact Statement. Atlanta, GA: Georgia Department of Transportation, 1988. Jones, Charles Jr. and Salem Dutcher. Memorial History of Augusta Georgia. Spartanburg, SC: Reprint Company Publishers, 1980. Lewis, Renee et al. Integrated Cultural Resource Management Plan For Fort Gordon, Georgia. Atlanta, GA: Fort Gordon Environmental Division / Natural Resources Branch, 2011. Milanich, Jerald T.. The Archaeology of Precolombian Florida. Gainesville; FL: University Press of Florida, 1994. White, Michael C.. Historic Milling in Richmond County. Warrenton, GA: CSRA Press, 1998. White, Michael C.. Waterways and Water Mills, Warrenton, GA. CSRA Press, 1995. Maps: Rowe, Heironymous. “Hopewell Interaction Sphere” (map), Wikipedia, accessed 6 August 2013. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Hopewell_Exchange_Network_HRoe_2010.jpg. Rowe, Heironymous. “Proposed Route of DeSoto Expedition” (map), Wikipedia, accessed 6 August 2013. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:DeSoto_Map_Leg_2_HRoe_2008.jpg. Southeastern Natural Sciences Academy. “Proposed Corridor of Savannah River Study” (map), Research. accessed 6 August, 2013. http://naturalsciencesacademy.org/aboutus/research/. Spyder_Monkey. “Central Savannah River Area” (map), Wikipedia, accessed 6 August, 2013. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Central_Savannah_River_Area.svg. Summers, George. Maps of Richmond County. Hand-drafted, 1928. Whaley , C. L.. Map of Richmond County, GA. Atlanta, GA: The Hudgins Co., 1908. Illustrations: 16 United States Mint. “Three Sisters Native American One Dollar Coin 2009” (image), Wikipedia. accessed 6 August, 2013. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:2009NativeAmericanRev.jpg.