Using Probiotics in Women with Irritable Bowel

advertisement

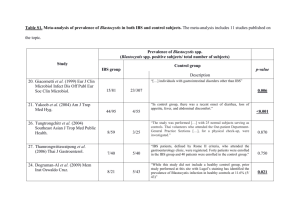

Using Probiotics in Women with Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a bowel movement disorder that is classified as diarrhea-dominant (IBS-D), constipation-dominant (IBS-C), or a combination of diarrhea and constipation (IBS-A). Standard treatment for this disorder is symptom management. This disorder is diagnosed when no organic causes are determined. Many of the patients diagnosed with this disorder have symptoms that never go away IBS is a disorder with multiple symptoms, such as cramping, abdominal pain, bloating, diarrhea, constipation, difficulty in passing stool, and urgency to have a bowel movement. This can cause much stress and discomfort for patients with IBS. Although IBS does not lead to any serious conditions such as cancer or other illnesses, about 1 in 5 Americans have IBS, and this creates about 1.3 million primary care visits for IBS annually, according to the Department of Health and Human Services (National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse [NDDIC], 2007). These patients’ lives are greatly impacted; they miss school and/or work and have a decreased social life due to their symptoms. On average, patients with IBS miss work three to four times as many days as the national average (Maxion-Bergemann, Thielecke, Abel, & Berggemann, 2006). Women with IBS are more likely to be diagnosed with endometriosis and are three times more likely to have a hysterectomy (Cole et al., 2005), which leads to unnecessary surgeries. The majority of the population who have IBS are women, but it is unclear why. There can be many contributing factors that can lead to IBS, including food sensitivities, stress, mobility impairment, medications (narcotics, iron, anticholinergics), medical disorders (diabetes, eating disorders, multiple sclerosis), history of sexual abuse, or a decrease of serotonin receptors (NDDIC, 2007). Standard treatment for IBS is geared towards the management of symptoms. In IBS-D management, fiber supplements are encouraged to increase bulk in stool and decrease stool frequency. In addition, Imodium can be used to decrease bowel frequency. Antispasmodics can be used to relieve pain and spasms for both IBS-D and IBS-C. In IBS-C, Miralax can be used daily to increase bowel movement and frequency. Donnapine and Librax can also be used for pain in IBS but can be habit forming. Tegasrod used to be the treatment of choice for women with IBS but was recalled due to a study that showed adverse cardiovascular effects. Specifically, women were having an increase in heart attacks, strokes, and angina with the use of tegasrod (NDDIC, 2007), so it was recalled in both the US and Canada. When standard therapy fails, why not use an alternative like a probiotic that has been shown in recent studies to work in patients with IBS? Probiotics are another form of treatment for alleviating symptoms in IBS; however, most clinicians are skeptical about using probiotics due to a lack of research. Probiotics are organisms that when taken orally can produce health benefits to an animal or human (Rachmilewitz et al., 2004). The most common probiotic used today is lactic acid, which helps with yeast infections. How does a probiotic work? It displaces the pathogens from an undesirable place by taking their place (O’hara & Shanahan, 2007) and shows anti-inflammatory response (Duke et al., 2004). Methods Since the emergence of probiotics in the field of gastroenterology, many studies have been done. These studies have tried many different species of probiotics, as well as many strains. This was done to determine which probiotics work best and at what strain level. Databases searched for recent studies conducted on the use of probiotics included Pub Med, Cochrane, Embase, CINAHL, UpToDate, and Stat!Ref, a database system for evidence-based practice journals. Words used for the search included IBS, irritable bowel, IBS and probiotics, and functional disorder. Dates included in the search were 2000 to 2009. Many articles have been written about the use of probiotics, but many are opinion articles based on the writer’s own research or practice. The search was narrowed to random control trials (RCT) that were double blinded and in English. This was done to increase the rigor of a study and examine a true experimental trial. By narrowing the search, a total of 317 RCT articles were found. The list was printed and titles were read. Many of the research articles included were not only limited to IBS, but also to particular single symptoms. Articles were not read if they did not include all symptoms of IBS and exclude infectious diarrhea and studies done in the pediatric population. One systematic review and one meta-analysis were found. Many of the reference articles listed in these articles were also on a list from a previous search found in the databases. The National Guideline Clearinghouse was also searched. Currently, there is no guideline for probiotic use with IBS patients. Literature Review Since many studies have been conducted, there has been a recent meta-analysis and systematic review published in 2008. The meta-analysis stated that probiotics could be used as a supplement to standard therapy for patients with IBS (Nikfer, Rahimi, Rahimi, Derakshani, & Abdollahi, 2008). The systematic review concluded that probiotics are efficacious in IBS but that the species and strain are uncertain (Moayyedi et al., 2008). Both of these articles looked at other articles from the same databases, such as Pub Med, Embase, and Cochrane. In the articles, the methods were discussed thoroughly. Words were identified for the authors’ searches, and the review process was described in great depth. The Jaded scale was used in both articles to grade the studies that were found. The Jaded scale grades a study based on randomization, double blinding, schedule, method of the double blinding, and whether the reasons for subjects dropping out of the study are described (Moayyedu et al., 2008). In extracting the studies, relative risk (RR) and confidence intervals (CI) were used to determine if the study was to be included in the analysis or review. In the meta-analysis, nine studies were chosen, and in the systematic review, nineteen were used. Many of the articles in the analysis were also in the review, with the exception of one. Both the analysis and the review explained the limitations encountered in the author’s search, such as small sample sizes and biases. The descriptions in the meta-analysis and systematic review described thoroughly the methods used in extracting the articles and in analyzing the data. Also, both described their biases, which increased the rigor of both articles. These studies looked at different species and strains of probiotics. Many studied the effects of Lactobacillus. In these studies, Lactobacillus did show an improvement in IBS symptoms, but the sample studied was less than 100 subjects, which decreased a true representation of a larger sample. Another form of probiotic studied was VSL#3, a combination of Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, and Streptococcus. This also showed to have some benefit, but when studies were extracted individually, the sample was also small, n=25, or the studies showed no significant improvement (Kim et al., 2003). Finally, the search was narrowed to one particular probiotic and looked at studies with a larger sample size. There have been two main studies that have shown that probiotics help alleviate symptoms in IBS. O’Mahony et al. (2005) studied the effects of two probiotics, Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, compared against a placebo. The results of this study concluded that Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 helped alleviate symptoms after 12 weeks of treatment, compared to no alleviation from Lactobacillus and the placebo, according to the VAS-IBS scale (visual analogue scale) (Bengtsson, Ohlsson, & Ulander, 2007) (see Table 1). This study included both male and female patients. Even though the sample size for this study was small n=67, the post treatment p value was significant (p=0.001) (O’Mahony et al., 2005). In another study, Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 was investigated with a larger sample size (n=362), which showed that symptoms of IBS were relieved (Whorwell et al., 2006). This study looked at different strengths of the probiotic and which worked best against a placebo. However, the sample only included women, which caused lack of rigor and an unclear representation of the population with IBS. In this study, p value was also significant (p=0.0118). Quigley, a co-author of the Whorwell study, took the data from the study and analyzed it. Quigley found that there was an increase in frequency of bowel movements in patients with constipation and a decrease in frequency in patients with diarrhea. The response rate and normalization effect were calculated, and p value was found to be p=0.05 (Quigley et al., 2006). This study was funded from the Higher Education Authority, Science Foundation of Ireland, and Proctor and Gamble. Proctor and Gamble was the company that provided the samples used in the study to find the strength that worked best. The authors did state that affiliations did not influence nor constrain any of the content of the article written. Synthesis of Literature Review Many of the studies conducted involved many different species and strains of probiotics. The search contained many articles on symptoms of IBS, but few actually studied the disease itself and a specific probiotic. The studies that were looked at were all RCT; however, very few had large study samples. Studies containing 100 or fewer participants were read over but lacked rigor due to small sample sizes. One of the studies had a sample size larger than 100. The outcome of this study showed great results. An analysis was done between baseline scores and scores from the probiotic group and placebo group. This showed a significant amount of improvement in bowel frequency and bowel urgency. It is shown in studies that Lactobacillus does not show any improvement in IBS compared to B. infantis. Recent research has shown that B. infantis does work well in female patients with IBS. It is shown to be safe and effective. It deceases diarrhea in IBS-D, helps with constipation in IBS-C, and is shown to help with IBS-A. Why not accept into practice something that has been shown to work for women? Let’s help female patients suffering from IBS avoid having unnecessary testing and surgeries, as well as misdiagnosis. Let’s change our practice and use probiotics that have been shown to help. Applying Guideline into Practice To apply this guideline into practice, the nurse practitioner (NP) would go to the chief of the department of medicine and gastroenterology and present the evidence of recent research done on B. infantis. Then the NP would also present the statistics on IBS showing how many women are having unnecessary procedures and how much money is spent on the diagnosis. There would be organizational issues since everything that the organization wants to implement now is required to be based on evidence-based practice and to be used for many years before it is accepted. There would be much resistance to this from physicians since a nurse practitioner is the one who did the research and wants to implement a change. The NP would present the same evidence as mentioned above. Also, a pilot study would be proposed in order to evaluate this new research. The NP would do all the necessary tasks needed to get it approved by the institutional review board (IRB). This guideline would then be evaluated through a pilot study done regionally. Then an interventional study can be done and do it through an RCT. Statisticians would be sought for analysis of the data to help determine if the B. infantis is effective. Adopting this guideline and letting an interventional study take place will show that the organization does want to implement evidence-based practice and show the members that it is taking a stand on a digestive disorder that affects many women. If, from the evaluation, B. infantis does show great benefits to women suffering from IBS, the organization can publish the results in its own journal so all the primary care providers know of recent updates in IBS.