anthropology, geertz, turner

advertisement

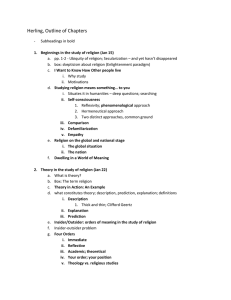

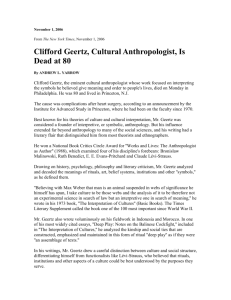

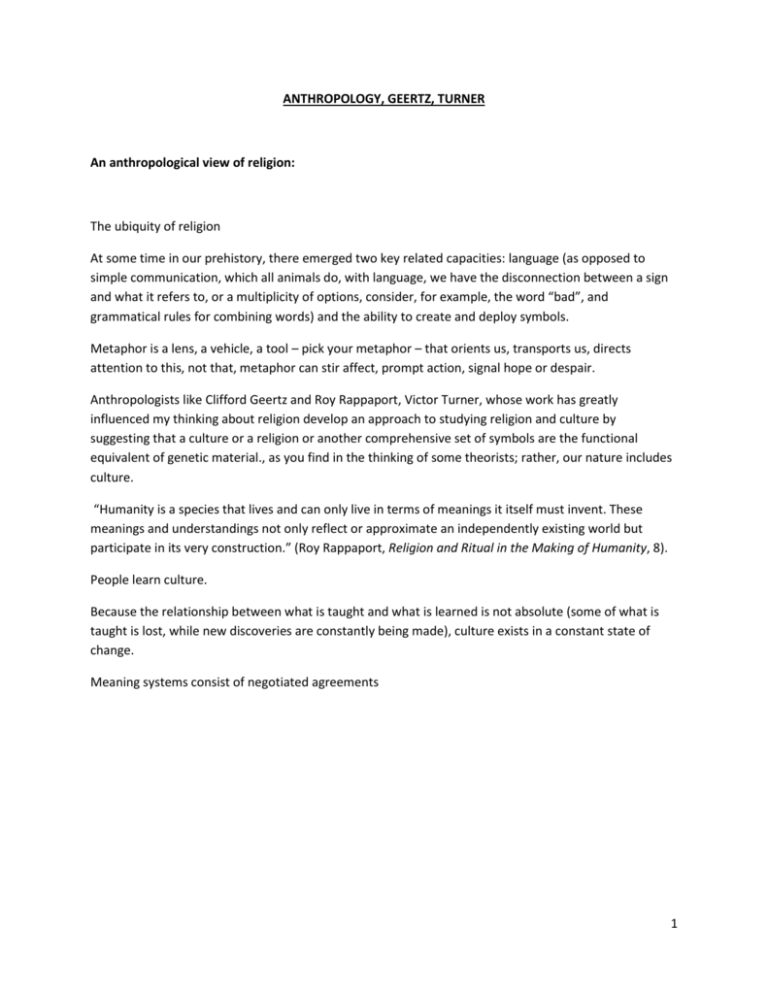

ANTHROPOLOGY, GEERTZ, TURNER An anthropological view of religion: The ubiquity of religion At some time in our prehistory, there emerged two key related capacities: language (as opposed to simple communication, which all animals do, with language, we have the disconnection between a sign and what it refers to, or a multiplicity of options, consider, for example, the word “bad”, and grammatical rules for combining words) and the ability to create and deploy symbols. Metaphor is a lens, a vehicle, a tool – pick your metaphor – that orients us, transports us, directs attention to this, not that, metaphor can stir affect, prompt action, signal hope or despair. Anthropologists like Clifford Geertz and Roy Rappaport, Victor Turner, whose work has greatly influenced my thinking about religion develop an approach to studying religion and culture by suggesting that a culture or a religion or another comprehensive set of symbols are the functional equivalent of genetic material., as you find in the thinking of some theorists; rather, our nature includes culture. “Humanity is a species that lives and can only live in terms of meanings it itself must invent. These meanings and understandings not only reflect or approximate an independently existing world but participate in its very construction.” (Roy Rappaport, Religion and Ritual in the Making of Humanity, 8). People learn culture. Because the relationship between what is taught and what is learned is not absolute (some of what is taught is lost, while new discoveries are constantly being made), culture exists in a constant state of change. Meaning systems consist of negotiated agreements 1 Clifford Geertz Geertz, Clifford (1926–2006). Born in San Francisco in 1926, Clifford Geertz attended Antioch College and majored in philosophy, later going to Harvard for graduate studies in anthropology. He completed two extended periods of fieldwork in Indonesia (Java first, then Bali) during and after his graduate training, then taught at the University of California, Berkeley and the University of Chicago. In 1970 he became the only anthropologist ever to gain an appointment at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey. He did later fieldwork in Morocco. A provocative and prolific author who gave philosophical depth to the more mundane details of anthropological reportage, he was one of the seminal thinkers who criticized the functionalist approach and used instead the analytical methods of symbolic anthropology. Geertz’s classic definition: “A religion is (1) a system of symbols which acts to (2) establish powerful, pervasive, and long-lasting moods and motivations in men by (3) formulating conceptions of a general order of existence and (4) clothing these conceptions with such an aura of factuality that (5) the moods and motivations seem uniquely realistic.”- The Interpretation of Cultures, New York: Basic, 1973, p. 90. Culture – knowledge people use to generate and interpret social interaction – culture is what is learned. Religion – those dimensions of culture that are most highly valued and construe as fundamental Geertz, some terminology symbolic anthropology: A style of ethnographic research utilized by Claude Lévi-Strauss and Clifford Geertz that took culture to mean a more-or-less systematic network of interlocking symbols that gives human activity meaning and helps orient people in the world. worldview: In general, the way a person or a community sees the world and understands its significance. Clifford Geertz opposes this to the term “ethos,” by which he means the predisposition to certain modes of action that a world view underwrites and legitimizes. ethos: Clifford Geertz’s term for the aspect of religion that motivates people to act in certain ways. He opposes this to “world view,” which is a religion’s way of seeing reality. thick description: A term used by Clifford Geertz to denote a way of writing ethnography. Whereas a “thin description” would only describe the surface details of a people’s cultural practices, a “thick description” would attempt to piece together the web of significations that make these practices an intelligible system. Geertz deftly sidesteps the age-old philosophical dispute over whether such form and order is discovered or constructed, and is content to affirm that the drive to generate meaningful symbolic forms is an integral aspect of human existence. For Geertz, anthropology need not seek to understand the basis of belief but rather belief’s manifestations. Geertz thus offers a relatively intuitive, open, and non-reductive way of conceptualizing religion. 2 WORLDVIEWS Now, to understand a religion’s or a culture’s view of the world, it requires a bit of work. An analytical chart might look something like the following. These various elements are interrelated. Our focus is one spaces and places. We come at the study of religion through the door of space and place, rather than, say, myth or doctrine or historical figures. Beliefs, attitudes, intentions, emotions, assumptions - all things are interconnected Actions - dancing, kneeling, singing Spaces, places - shrines, sanctuaries, rocks Time, rhythm - holidays, seasons, eras Objects - masks, fetishes, icons - congregations, sects Groups Identity: figures, roles - gods, ancestors, shamans, priests Qualities & quantities - circularity, seven Languages, sounds - stories, chants, music Smells? 3 Victor Turner (1920-1983) Turner was especially interested in Arnold Van Gennep’s discussion of the liminal phase in passage rites. Separation – transition - incorporation Two key notions in his theory of rites of passage are "Liminality and Communitas" 1. Most important contemporary theorists of ritual a. Liminality, the liminoid, communitas b. Occurs in rituals of status elevation (e.g., initiation) c. Occurs in rituals of status reversal (e.g., festivals, clowning) d. Liminality vs. status system + transition / state communitas / structure equality / inequality sacredness / secularity sexual continence / sexuality minimal gender distinction / maximal 2. Revised our idea of ritual: processual as well as structural 3. Importance of inversion, court jesters 4. Extended to include "liminoid" Victor Turner’s model of social - social conflict is dramatic, and he identifies four phases in a social drama: breach, crisis, redress, reconciliation or irreparable breach. Turner associates ritual (in a strict sense) with liminality, reflexivity, and a subjunctive mood. “Liminality,” writes Turner, “can perhaps be described as a fructile chaos, a fertile nothingness, a storehouse of possibilities, not by any means a random assemblage but a striving after new forms and structure, a gestation process, a fetation of modes appropriate to and anticipating postliminal existence.” Ritual then is potentially transformative insofar as it allows the “the contents of group experiences [to be] replicated, dismembered, remembered, refashioned, and mutely or vocally made meaningful” (Turner 1991:12,13). 4