Precis three: peirce charles sanders (19th century pragmatism) by

advertisement

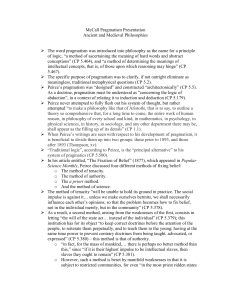

PRECIS THREE: PEIRCE CHARLES SANDERS (19TH CENTURY PRAGMATISM) by Jeonghyun (Esther) Kwon Box #1425 A CLASSROOM ASSIGNMENT Submitted to Dr. James Moore in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the course ES 9750 Historical and Philosophical Foundations of Education at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School Deerfield, Illinois January, 2016 Peirce Charles Sanders Biographical Information Peirce Charles Sanders (1839-1914) was born on September 10, 1839 in Massachusetts. His father, Benjamin Peirce was a mathematician and astronomer at Harvard, and his mother, Sarah Hunt Mills, was a daughter of Senator Elijah Hunt Mills. Peirce grew up under his father’s high view of children’s individuality and with intellectual visitors’ frequent visit to his home. Benjamin, one of the prominent scientists during the time, immensely influenced his son’s learning through heuristic teaching. Graduated from Harvard, Peirce worked for the U.S. Coastal Survery and Johns Hopkins. His affair with a mistress made him lose his position at Johns Hopkins. He could not work for Coastal Survey because of the accusations of financial impropriety. He could no longer deliver a lecture at Harvard because of his potential of influencing the students with immorality. Peirce died of cancer on April 1914. (The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy) Historic and Philosophic Context Peirce was the founder of American pragmatism. Heavily influenced by Peirce, William James and John Dewey popularized pragmatism (Atkin). Pragmatism is “a philosophy that encourages us to seek out the processes and do the things that work best to help us achieve desirable ends (Ozman 2012, 113).” Pragmatism studies ideas, attempts to apply in daily life, and generates ideas for the changing world (Ozman 2012). Pragmatism has been predominant in American philosophy for last hundred years (Knight 1989). The Scientific Revolition’s questioning mind and naturalistic humanism have fostered the development of pragmatism (Ozman 2012). Pragmatism can be traced in Francis Bacon, John Locke, Jean-Jacque Rousseau, and Charles Darwin (Ozman 2012). Charles Sanders Peirce, William James, and John Dewey are the ones who actualized pragmatism. Pragmatism has greatly influenced education through the progressives’ reconstructionism, futurism, and educational humanism (Knight 1989). Peirce’s Key Concepts “How to Make Our Ideas Clear” “How to Make Our Ideas Clear,” Perice’s influential article, was published in Popular Science Monthly in 1878. In this article, he crystalized his epistemology. He dichotomized mind (subjective) and material reality (objective), but he argued that objective reality is in one’s idea about the given object (Ozman 120), as he put it, “Our idea of anything is our idea of its sensible effects; and if we fancy that we have any other we deceive ourselves, and mistake a mere sensation accompanying the thought for a part of the thought itself (Peirce 1878).” According to this logic, it is important for Peirce to make ideas clear. For Peirce, an unclear idea was an impediment to the fulfillment of human intelligence, as he says: “It is terrible to see how a single unclear idea, a single formula without meaning, lurking in a young man’s head, will sometimes act like an obstruction of inert matter in an artery, hindering the nutrition of the brain, and condemning its victim 3 4 to pine away in the fullness of his intellectual vigor and in the midst of intellectual plenty. (Peirce 1878)” Peirce urged people to consider the consequences of an idea in order to make an idea clear because ideas cannot be separated from human conduct (Ozman 2012). For Peirce, an idea is awareness to its effects and consequences (Ozman 2012). He said, “Consider what effects, that might conceivably have practical bearings, we conceive the object of our conception to have. Then our conception of these effects is the whole of our conception of the object. (Perice 1878)” “The Fixation of Belief” Peirce believed that inquiry is the process of fixation of belief. Peirce argued that doubt triggers this process. Peirce believed that the method of science satisfies human doubts because the method is untainted by human opinions and will eventually lead to the ultimate Truth, as he said, “To satisfy our doubts, therefore, it is necessary that a method should be found by which our beliefs may be caused by nothing human, but by some external permanency—by something upon which our thinking has no effect. … the method must be such that the ultimate conclusion of every man shall be the same. Such is the method of science. (Peirce 1877)” Peirce’s trust in the method of science anchors in realism. He believed that a person can approach to the ultimate truth through experience and reason: “There are real things, whose characters are entirely independent of our opinions about them; those realities affect our senses according to regular laws, and, though our sensations are as different as our relations to the objects, yet, by taking advantage of the laws of perception, we can ascertain by reasoning how things really are, and any man, if he has sufficient experience and reason enough about it, will be led to the one true conclusion.” (Peirce 1877) Peirce underscored that an idea should be tested by experience, as he described, “But let a man venture into an unfamiliar field, or where his results are not continually checked by experience, and all history shows that the most masculine intellect will ofttimes lose his orientation and waste his efforts in directions that bring him no nearer to his goal, or even carry him entirely astray (Peirce 1877).” Peirce’s emphasis on empiricism has triggered the burgeoning of pragmatism. John Dewey, once a student of Peirce, later said that Peirce built more on what Locke argued by presenting that knowledge is not only impressed on a blank tablet but also formed through interconnection of experiences (Ozman 2012). Bibliography Albert Atkin. 2016. “Charles Sanders Peirce.” The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Accessed January 22. www.iep.utm.edu. Chalres S. Peirce. 1877. “The Fixation of Belief.” Popular Science Monthly 12 (November): 1–15. Charles S. Peirce. 1878. “How to Make Our Ideas Clear.” Popular Science Monthly 12 (January): 286–302. Knight, George R. 1989. Philosophy and Education: An Introduction in Christian Perspective. 2nd ed. Berrien Springs, Mich: Andrews University Press. Ozmon, Howard. 2012. Philosophical Foundations of Education. 9th ed. Boston: Pearson. Phyllis Chiasson. 1999. “Peirce and Philosophy of Education.” Encylopaedia of Educational Philosophy and Theory. Port Townsend, WA: Peninsula College. http://eepat.net/doku.php?id=peirce_and_philosophy_of_education. Robert Burch. 2014. “Charles Sanders Peirce.” Standford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.