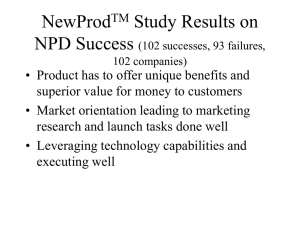

Table 1.3 The three main streams of research within

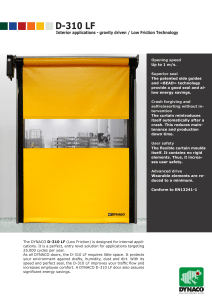

advertisement