here - Society of Breast Imaging

advertisement

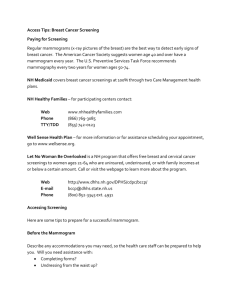

July 29, 2011 – Response Statement Autier P, Boniol M, Gavin A, Vatten LJ. Breast cancer mortality in neighboring European countries with different levels of screening but similar access to treatment: trend analysis of WHO mortality database. BMJ 2011;343:d4411 doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4411 In the current issue of the British Medical Journal, Autier and colleagues claim that there is no evidence that mammography screening has played a direct role in breast cancer mortality reductions in countries in which screening has been implemented. The investigators compared breast cancer mortality trends in three pairs of adjacent countries (Sweden vs. Norway; Northern Ireland vs. Northern Ireland; and Belgium and Flanders vs. Netherlands). Each comparison matched a country that introduced mammography screening some years earlier (Sweden, Northern Ireland, and Netherlands) with a comparison country that introduced mammography screening later (Norway, Republic of Ireland, and Belgium and Flanders). Comparing the trend in breast cancer death rates between 1989-2006, the authors concluded that the trends in the reduction of breast cancer deaths in each country pair were similar, and thus that improvements in therapy, not mammography, was the likely explanation. Measuring the impact of screening at the population level is challenging, but has been done successfully. Specifically what is required at a minimum is to take into consideration: (1) when mammography was introduced; (2) how long it took to invite the target population: (3) the age range of the target population, and the initial and repeat attendance rate; (4) having an adequate screening period and follow-up period; (5) adjusting for confounders such as trends in the underlying incidence of disease, selection bias, etc., and perhaps most important, (6) the ability to isolate breast cancer deaths attributable to incident cases that occurred before screening was offered to the population. The latter is very important because it has been shown that approximately 50% of breast cancer deaths in a ten year period are attributable to cases diagnosed before the start of that period. A good example of this sort of analysis is the recent study of mortality trends in incidence-based mortality among women ages 40-49 in Swedish counties that did and did not offer mammography screening.1 With 16 years of follow-up, there was a 29% lower incidencebased mortality among women ages 40-49 who attended screening in the counties that offered screening compared with the ones that did not. The authors of this new analysis frame their analysis comparing mortality trends in adjacent countries as similar to the analyses that showed significant reductions in cervical cancer mortality in the Nordic countries based on the timing of the introduction of screening. However, the potential to see mortality reductions of similar magnitude is probably less with breast cancer screening for several reasons, including much poorer survival for invasive cervical cancer compared with breast cancer, and the fact that cervical cancer screening contributes to mortality reductions through prevention and early detection. Still, while it would seem intuitive that there would be differences in the breast cancer mortality trends in the countries that offered screening earlier, failure to address the methodological considerations listed above are the main reasons why these authors mistakenly conclude that mammography is not have an impact on breast cancer mortality. For example, not all women who develop breast cancer are in the group invited to screening, and not all women who are invited to screening attend screening. To see the true benefit of screening in a population, it is important to isolate screened and unscreened cohorts. This is an elementary epidemiological principle. Second, just because two countries are adjacent doesn't mean that their breast cancer mortality trends are easily compared without adjusting for other factors. For example, compared with Norway, Sweden has about 10% greater breast cancer incidence during the study period, and it was even greater before the study period began. Higher incidence rates will influence mortality rates, since mortality rates are a function of incidence rates over time and their corresponding survival. The authors did not adjust for differences in the incidence rates between countries. Third, Sweden began introducing screening in 1986, but not all counties introduced it in that year, and of course, not all women received a mammogram in 1986. It takes time to invite the population to screening, and full implementation didn't occur until 1992-1993. Third, in each of these comparisons mortality data are contaminated with deaths attributable to breast cancer diagnoses that occurred before screening was introduced. During the period 1986-1996 (and thus, also 1993-2003) half of the breast cancer deaths are attributable to a diagnosis before screening was even offered, let alone fully implemented. Thus, in addition to the other shortcomings, this analysis has insufficient time to measure a population wide effect. Finally, we don't know how effectively mammography is functioning in the countries in these comparisons. The effectiveness of mammography on a population-wide basis will be influenced by the attendance rate and the accuracy of the screening. At the most fundamental level, the findings of this study are easily discarded due to (1) methodological shortcomings, and (2) the large body of evidence ranging from randomized controlled trials, case-control studies, and large population based evaluations of service screening that demonstrate a benefit from screening. 1. Hellquist BN, Duffy SW, Abdsaleh S, et al. Effectiveness of population-based service screening with mammography for women ages 40 to 49 years: evaluation of the Swedish Mammography Screening in Young Women (SCRY) cohort. Cancer 2011;117:714-22. Robert A. Smith, PhD | Director, Cancer Screening National Home Office | American Cancer Society, Inc.