Model Justification Essay – Moral Reasoning

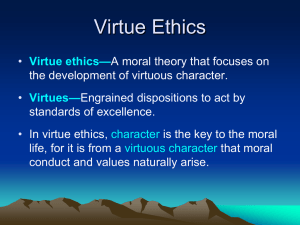

advertisement

1 Student name: Instructor name: A-PHIL 3327: Justification Essay Date: My moral dilemma consisted of a friend who, sober for twelve years, started drinking again and whether I, as a bartender but also as his friend, would confront him about it by refusing to serve him. The values I considered when analyzing the moral dilemma included (but were not limited to) honesty, respect, loyalty, tolerance, compassion, courage, love, life, autonomy, privacy, community and friendship. In applying these values to both sides of the dilemma I found that, though they overlapped a great deal, the strongest arguments all pointed to confrontation over silence. The primary value that supported this reason was that of friendship, which I felt incorporated all the other values I considered. Based on what I value in a friendship – compassion, respect, love and honesty – I have a moral obligation to refuse to serve my friend and be candid about the reasons. The moral rule guiding this decision is that a true friend is honest. For Virtue Ethics, this moral rule finds its root in the notion of the character of the individual. It has at its core a question: what kind of friend do I want to be? The philosophical theory of Virtue Ethics began with the Greeks and notably found expression with Aristotle, who believed that human beings were born with natural internal tendencies that had to be nurtured into character traits by society to reach their full virtuous potential (Athanassoulis). This classical version, known as Eudaimonistic ethics, has two key components: first it presumes that morality and life are coterminous and therefore should not be 2 divided into separate spheres of attention or impact; and second, it asserts that everyone has a duty to moral development and growth. Aristotle’s coterminous claim that the good is good for us ((Pojman 166) extends to the duty of moral growth because the good is also good for the community. Pursuing and perfecting the virtues allowed individuals to achieve eudiamonia (commonly translated as “flourishing”) setting an example which extended to the social sphere, benefitting the entire community. This aspect of a responsibility to moral evolution is distinctive to Virtue Ethics in that it sees morality as both an achievement and an ongoing assignment: the more virtuous we are, the more virtuous we become – to the advantage of ourselves and society. Inherent in this notion of moral growth is a promise of capacity: all people can achieve some level of virtue as “a matter of degree” (Hursthouse 3), increased through our efforts. The duty to moral growth has an appealing momentum in parallels to aspects of intellectual growth: the more effort we exert, the more we attain. When I ask myself what type of friend I want to be, I consider those traits I value in friendship; the more I cultivate the virtues of friendship the more readily and easily I will act on those virtues as they become a part of my character, in part because I have worked to make them so. The principles of Virtue Ethics emphasize the role of character in the habituation of virtuous traits, taking into account the motives and emotions inevitably involved in moral decisions. Virtue Ethics is concerned with who we are as much as with what we do. This internal focus sets Virtue Ethics apart from both deontological “rule” and consequentialist “result” theories where the morality of the action is either a rigidly prescribed rule in the former or dependent upon the consequences in the latter. Virtue Ethics places a premium on being rather than doing by asking us to consider what kind of person we want to be (Pojman 166). In the example of my moral dilemma, I must consider my values, emotions and inclinations when 3 making a moral decision, and I have to ask what constitutes friendship. What examples do I have to guide me? In the past I had a friend who, in his confrontation of my behavior, exhibited great concern and care for me. I found my respect for him elevated by his willingness to engage in something unpleasant (confrontation) in order to preserve something of great value (friendship). The premium he placed on honesty made an impression on me. If that is the kind of friend I want to be, I have an obligation to be honest with my friend not just for his sake, but for the sake the values, or virtues, I seek to cultivate in myself as well. This communal feature of Virtue Ethics is important because it relates to the interconnected aspect of a virtuous inner moral life and social flourishing. Led by the examples of the virtuous, we practice and nurture good character traits in ourselves, leading us to become good people who act virtuously because we have cultivated a disposition to do so: we are good for the sake of being good and in doing so we become an example for others, fostering further goodness in society. Critics assert a deficiency of moral direction in classic Virtue Ethics by claiming that it suffers from “a problem of application” (Pojman 176): because it “does not produce codifiable principles” (Hursthouse 6) it cannot tell us what to do. Pojman quotes William Frankena in assessing this perceived weakness of Virtue Ethics: “Traits without principles are blind, but principles without traits are impotent” (179). An incorporation of Virtue Ethics with Deontic ethics sought to include guiding principles or “countervailing virtues” that corresponded with what might be considered primary virtues: fairness, honesty, beneficence, and non-maleficence (Pojman 178). This principle-guided form of Virtue Ethics placed the emphasis on the rule to indicate the virtue: each would be assessed separately as the rule would be primary and the virtue would supplement motivation (Hursthouse 7). 4 . While the Correspondence Thesis does help alleviate Virtue Ethics’ anemic overt guidance, it resorts to the deontic emphasis on action: on doing rather than being. This compromises the inherent value of virtues: that they “are not merely instrumental but constitutive of the good life” (Pojman, 181). One of the lovely aspects of Virtue Ethics is its faith in humanity; these inclinations that are innate can be nurtured to fruition by a conscientious society. It’s a way of saying we all have the potential to be good; that we even have a natural inclination toward it that can be encouraged (or thwarted) over the course of our lives. When we make morality prescriptive we compromise the autonomy that is an inspirational aspect of being virtuous. If I am honest with my friend primarily from a duty to tell the truth, with the virtue of being an honest person secondary to action taken on the behalf of a principle, I compromise my moral growth (and negate an example for others to emulate) because I was directed externally to do so rather than compelled from internal inclinations toward the virtue of honesty. Another criticism about Virtue Ethics lack of codifiable principles is that the virtues cannot be easily delineated or universalized. How do we identify the virtues when the theory itself acknowledges that Cultural Relativism means societal virtues change across time and communities? But Virtue Ethics’ encouragement of moral growth offers the potential for cultural change, an extension of how the good is good for us and society as well. A responsibility to moral growth equates to an ethical evolution that helps societies as well as individuals flourish. Action-based ethics like Deontology and Consequentialism may prescribe our actions but do not equate to a moral, or virtuous, life because they simply tell us what to do, not how to be. Duty for duty’s sake does not enhance our moral character; acting in the anticipation of the best overall consequences fails to consider the individual role in the moral equation. Virtue Ethics combines a duty for moral growth with individual intuition for moral behavior by incorporating 5 emotions, motives, inclinations, character, relationships, and situational discernment. This intuitive appeal is engaging rather than prescriptive. It allows us to be good and feel good about it because the choice we make is a reflection of who we are (or hope to be). But Virtue Ethics’ emphasis on emotions has a complication: how do we avoid slipping to the extremes of excess or deficiency in regard to our character traits? The range of expression exists as a wide continuum between too little or too much. Aristotle posited the Golden Mean to discern moderation of the virtues: we use our unique human reasoning (which Kant would like) to determine the medium of the extremes relative to each of us. Note that the focus is still internal. This internal locus on the agent does not descend into Egoism, as occasionally asserted in criticisms, because Virtue Ethics emphasizes responsibility to the community in the individual duty to moral growth. According to Pojman, Aristotle claimed the virtues were “simply those characteristics that enable individuals to live well in communities” (172) so that society could flourish. The moral virtues must be taught by example and exercised to be incorporated into the good character. This necessitates a virtuous model for others to emulate so they might practice in order to become virtuous. With regard to my moral dilemma I must decide the medium of friendship (with hostility as the deficiency and obsequiousness as the extreme) and honesty (with deception as the deficiency and brusqueness as the extreme) with regard to this specific dilemma. It’s up to me to find the medium that allows me to express and nurture the virtues of honesty and friendship that I value for myself. This is the learned, or experienced, aspect of Virtue Ethics: that we must practice or habituate ourselves to the morally virtuous life. The motivational aspect of Virtue Ethics is a particularly strong point in the philosophy. The duty it requires of us (moral growth) is not a grudging obligation but an opportunity: it 6 offers inspiration even as it incorporates the very same emotions and inclinations that Kant’s deontological system would have us deny and consequentialist systems would have us ignore. Virtue Ethics wants me to consider my inclinations and emotions concerning the moral dilemma I face with my once-sober friend. My compassion for his struggle with addiction is important; my concern for his family, friends, and the community as a whole is equally valid. These responses to my friend’s plight stem from character traits that should act in concert to help me reach a decision with regard to my moral dilemma. The difficulty with Virtue Ethics is that it will not tell me what the right choice is: there is no rule I can readily apply, no scale of consequence I can reference that solves my moral dilemma for me. This is Virtue Ethics’ blessing and its curse: the autonomy it affords me can also seem to abandon me to the whims of circumstance. It suggests that, similar to economic and social schisms, some people might be positioned for moral growth more favorably than others. If I have never had a good friend or my friendships have been poor in quality, I have no virtuous example to emulate. My moral development might be stunted by the conditions and events of my life. Morality consists of rules and guidelines used to assign praise or blame for behavior; could Virtue Ethics blame the victim of circumstance? Virtue Ethics retorts that the duty to moral growth suggests a promise of capacity: human beings have inherent traits that can be developed to achieve some level of virtue as a matter of degree, increased through effort. The internal locus on the agent allows for such degrees of virtuous attainment, though with the evidently elitist understanding that some will reach greater heights of virtue than others. But Virtue Ethics also places a duty on society at large through the individual duty to moral growth; we can all be examples as we continue our efforts toward excellence, providing the necessary resources for virtuous growth in our community. 7 If I said nothing to my friend about my concerns, I could retain the friendship and he would be none the wiser. And on some level I could still consider myself his friend because I had extended compassion, loyalty and tolerance toward him. But Virtue Ethics demands an emphasis on the character of the moral agent, not the action he or she takes or the consequences that derive from it. By confronting my friend about his drinking, at a minimum I protect both my friend and the community from him driving home drunk; a consequentialist result. From a deontological perspective I should be truthful with my friend out of duty to both my employer and a moral duty to be honest. Both theories can be applied to my ultimate decision to confront my friend about my concerns. But they represent a minimalist approach to morality: Kant seems rigid and cold, while consequentialism reduces morality to a mathematic equation. Virtue Ethics supplies an internal motivation which compels me to candid confrontation because of the kind of moral life I want to lead and have a duty to develop. Virtue Ethics asserts that as I display the virtues of honesty and friendship, I set an example for others even as I reinforce those traits within myself. Intuitively, Virtue Ethics makes the most sense to me as it seems to incorporate the individual and society in morality. The internal focus is important to me: that instinctive, gnostic sense of knowing what is right and wrong is part of what we talk about when we discuss good character. The people we hold in esteem reflect what we value; what we want for and cultivate in ourselves. I don’t believe I should remove my emotions and inclinations from a moral dilemma when reaching a decision; it seems intrinsic to me that any conclusion I reach is shaped by them. Action-based theories fall short of incorporating the human element on both the individual and communal scale. With Virtue Ethics, a spiritual need is fulfilled as I endeavor to 8 reach a decision which incorporates my emotions, intuitions, experience and knowledge with my desire to develop a virtuous life: to be good for goodness sake. Works Cited Athanassoulis, Nafsika. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. University of Tennessee at Martin, 2010.Web. 7 March 2011. Hursthouse, Rosalind. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford U, 2007. Web. 7 March 2011. Pojman, Louis P. How Should We Live? An Introduction to Ethics. California: Thomson, 2005. Print.