Whiskey Rebellion of 1794: Washington's Response

advertisement

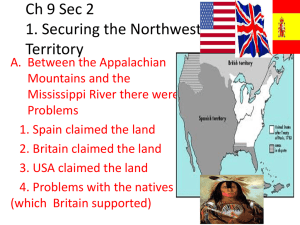

Many of the Founders, including George Washington, believed that one weakness of the Articles of Confederation was that the federal government could not deal firmly with domestic uprisings such as Shay's Rebellion. George Washington, always aware that as the new nation's first President, his every action would be "drawn into precedent," conducted himself both deliberately and decisively when farmers across the US resisted a new federal excise tax on liquor. The Constitution, ratified in 1789, created a strong central government. To support federal power to enforce the law, Congress passed the Militia Law of 1792. This law allowed Congress to raise a militia to "execute the laws of the union, (and) suppress insurrections." At the same time, to avoid the financial problems experienced under the Articles, the Constitution allowed the federal government to collect certain kinds of taxes. In 1791, Congress placed an excise tax of 25 % on the sale of whiskey and other liquor. The tax—ranging from 7 to 18 cents per gallon—was a direct tax on the people who made and sold whiskey. The tax was intended to help shift resources from individuals to national programs, such as building roads and establishing post offices, as well as supporting a western defense. Farmers west of the Appalachian Mountains (from Pennsylvania to Georgia) bitterly opposed the whiskey tax. These farmers were unable to move their grain to far away markets and still make a profit, so instead they distilled their grain into whiskey. Jugs of whiskey could be traded for supplies locally, and therefore the liquor was actually used as a form of currency, as money was often scarce. Moreover, the jugs of whiskey were more easily exported over the mountains to profitable markets in the east. Some farmers called for the abolishment of the tax because they believed it was imposed unfairly on people in only one part of the country. Others thought of themselves as patriots for refusing to pay taxes, in the same way that the American colonists had refused to pay taxes to England. And, many Americans along the frontier resented the tax from a distant legislature in the east. There were outbreaks of opposition, and in rural areas where no one was willing to serve as tax collector, the taxes went unpaid. By July of 1794, the tension had reached a breaking point. Tax collectors were harassed, tarred and feathered in many small towns; one collector’s home was burned. In Western Pennsylvania, the rebellion was intense. Reports told that six thousand people were camped outside Pittsburgh threatening to march on the town. Washington believed he had to act. He and his cabinet members met with Pennsylvania officials. They decided to present evidence of the violence to Associate Justice of the Supreme Court James Wilson. After reviewing the evidence, Wilson certified that the situation could not be controlled by civil authorities alone. A military response could proceed. On August 7, Washington issued a proclamation commanding all “insurgents” to “disperse and retire peaceably to their respective abodes.” He cited his authority under the 1792 Militia Act. But the rebellion continued. September 25, 1794, he issued another Proclamation which read in part, “… I, George Washington, President of the United States, in obedience to that high and irresistible duty consigned to me by the Constitution ‘to take care that the laws be faithfully executed,’ … do hereby declare and make known that… a militia…force which…is adequate to the exigency is already is motion…” Washington recruited militia members from Pennsylvania as well as nearby Maryland and New Jersey. In total, there were almost 13,000 men—about as many as had served in the entire Continental Army that defeated the British. Washington personally led the troops into Bedford—the first and only time a sitting US President has led troops into the field. By the end of November, more than 150 people had been arrested; most were later freed due to lack of evidence. Two were convicted of treason, but Washington later pardoned them. Washington’s strong response to the Whiskey Rebellion became, as future-President James Madison put it, “a lesson to every part of the Union against disobedience to the laws.” Whiskey Rebellion Flag Washington was always aware that as the first president he was establishing precedents, or examples that would set a path forward toward the future. He knew that he could not allow such a blatant disregard for the rule of law. He believed that if any group was permitted to disobey the law, “there is an end put at one stroke to republican government, and nothing but anarchy and confusion is to be expected thereafter.” Later that year, Washington commented on the rebellion in his Sixth State of the Union Address: It has demonstrated that our prosperity rests on solid foundations; by furnishing an additional proof that my fellow-citizens understand the true principles of government and liberty; that they feel their inseparable union; that, notwithstanding all the devices, which have been used to sway them from their interest and duty, they are now as ready to maintain the authority of the laws against licentious invasions, as they were to defend their rights against usurpation. It has been a spectacle, displaying to the highest advantage the value of republican government…. Please answer the following questions: 1. What federal law was the focus of protests in the Whiskey Rebellion? 2. Why did President Washington consider using military force against the protestors? 3. How did Washington involve other branches and levels of government in his decision? 4. The Constitution assigns the President the responsibility to “take care” that laws are “faithfully executed” and makes him or her commander in chief of the military. How did Washington understand these duties? 5. Do you feel Washington was right in using military force? Why or why not?