SECONDARY MILD/MODERATE EDUCATIONAL SPECIALIST INVOLVEMENT

IN TRANSITION PLANNING FOR STUDENTS WITH INDIVIDUAL EDUCATION

PLANS

A Thesis

Presented to the faculty of Graduate and Professional Studies in Education

California State University, Sacramento

Submitted in partial satisfaction of

the requirements for the degree of

MASTER OF ARTS

in

Education

(Higher Education Leadership)

by

Ashley Rebekah Latimer

SPRING

2013

© 2013

Ashley Rebekah Latimer

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

ii

SECONDARY MILD/MODERATE EDUCATIONAL SPECIALIST INVOLVEMENT

IN TRANSITION PLANNING FOR STUDENTS WITH INDIVIDUAL EDUCATION

PLANS

A Thesis

by

Ashley Rebekah Latimer

Approved by:

__________________________________, Committee Chair

Virginia L. Dixon, Ed.D.

__________________________________, Second Reader

Hazel Mahone, Ed.D.

Date

iii

Student: Ashley Rebekah Latimer

I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University

format manual, and that this thesis is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to

be awarded for the thesis.

, Graduate Coordinator

Geni Cowan, Ph.D.

Date

Graduate and Professional Studies in Education

iv

Abstract

of

SECONDARY MILD/MODERATE EDUCATIONAL SPECIALIST INVOLVEMENT

IN TRANSITION PLANNING FOR STUDENTS WITH INDIVIDUAL EDUCATION

PLANS

by

Ashley Rebekah Latimer

Brief Literature Review

IDEA 2004 mandates a transition plan be part of students with disabilities’

Individual Education Plan (IEP) from the age of 14 through the time they leave their

secondary education [IDEA 2004, §300.320 (b)]. Despite the letter of the law and

transition plans being implemented, the post secondary outcomes for students with mild

to moderate disabilities continue to be dismal in comparison to their general education

peers (National Center for Educational Statistics [NCES], 2003).

Statement of the Problem

Many special education teachers at the secondary level have little to no training in

the complex and critical process of planning and implementing the transition piece of the

IEP (Test, 2009). The purpose of this study was to determine the level of training and

involvement of secondary special education teachers in the Elk Grove Unified School

District in five identified components of the Transition planning process for students with

v

mild to moderate disabilities with an Individual Education Plan. The secondary purpose

of the study was to determine what effect, if any, these teachers’ pre-service and inservice training had on their level of involvement in each category.

Methodology

A 35-item questionnaire regarding Transition Involvement and Competency was

distributed to all members of the target sample. The questionnaire rated secondary

special educators’ levels of involvement in five identified components of a transition plan

and asked respondents questions about their pre-service and in-service training regarding

the five components.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The results of the survey suggested secondary special education teachers are most

involved in the transition planning components in which they have received the most

training and least involved in those who had received little to no training. District Special

Education Administrators should consider creating in-service opportunities for their

secondary special educators based upon the identified components in which pre and/or inservice training was lacking. The in-service should include a handbook/guide in

conjunction with the areas where competency is lacking to be used as a resource and

vi

reference. Future research should be conducted to see if the trends and correlations

shown in this study have further implications with a broader sample population of

secondary special educators and determine if this study’s findings can be generalized.

, Committee Chair

Virginia L. Dixon, Ed.D.

Date

vii

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

It is with immense gratitude that I acknowledge the support and help of my

committee chair, Dr. Virginia Dixon, who has advised me both in matters of thesis and

career path. Without her guidance and push toward scholarly excellence, completing this

thesis might have proved impossible.

I would also like to thank my committee member, Dr. Hazel Mahone, who also

acted as my thesis advisor for the first half of my work. Her faith in me as a writer,

educational leader, and person gave me the motivation I needed to press on in the face of

challenges along the way.

In addition, thank you to the Graduate Coordinator, Dr. Geni Cowan, who first

taught me how to approach my topic with the mind of a true researcher in her Research

Methodology course. Her enthusiasm for and work ethic in matters of research were

nothing short of inspiring to me.

viii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Acknowledgments............................................................................................................ viii

List of Tables ..................................................................................................................... xi

Chapter

1. INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................................1

Background ..............................................................................................................1

Statement of the Problem .........................................................................................2

Definition of Terms..............................................................................................................3

Significance of the Study .........................................................................................4

Organization of the Remainder of the Study ...........................................................5

2. REVIEW OF THE RELATED LITERATURE ............................................................6

Introduction ..............................................................................................................9

Post-secondary Outcomes for Students with Disabilities ........................................9

Evidence-based Components of Transition Planning ............................................13

Special Educators’ Perceived Competencies and Involvement in Transition .......19

The Role of Leadership and Administration in Transition Planning .....................22

Rationale for the Study ..........................................................................................26

Summary ................................................................................................................26

3. METHODOLOGY ......................................................................................................28

Population and Sample ..........................................................................................28

ix

Design of the Study................................................................................................28

4. DATA ANALYSIS ......................................................................................................32

5. SUMMARY, CONCLUSIONS, AND RECOMMENDATIONS...............................46

Appendix. Questionnaire .................................................................................................. 49

References ..........................................................................................................................53

x

LIST OF TABLES

Tables

Page

1.

Secondary Mild/Moderate Educational Specialist Involvement............................33

2.

Secondary Mild/Moderate Educational Specialist Pre-Service Training ..............37

3.

Secondary Mild/Moderate Educational Specialist In-Service Training ................41

4.

Secondary Mild/Moderate Educational Specialist Combined Pre- and

In-Service Training ................................................................................................44

xi

1

Chapter 1

INTRODUCTION

Background

Transition is a required part of an Individual Education Plan for students aged 16

and older, per the reauthorization of IDEA in 2004. The policy was set forth to increase

secondary graduation rates and successful post-school outcomes in the areas of education,

employment, independent living, and participation in the community for students with

mild to moderate disabilities. Although best practices in transition, addressing both

academic and functional achievement, have been researched and promoted over the last

10 years, the percentage of students with disabilities not graduating secondary is still

disproportionate to that of their non-disabled peers (National Center for Educational

Statistics [NCES], 2003). Additionally, these students are still experiencing difficult

transitions into their post-school lives. Multiple factors contribute to the substantial

number of unsuccessful transition outcomes from school to adult life for students with

disabilities (Test, Fowler, White, Richter, & Walker, 2009). Consequently, much

research has been conducted to examine the related areas of policy, outcomes, and

evidence-based practices in transition to improve these outcomes.

A critical component to consider in improving post-secondary outcomes is special

educators’ training background and involvement in the transition process. In addition to

teaching academics, secondary special educators bear increasing responsibilities as the

2

implementers of transition planning, assessment, and coordination with a variety of

agencies and persons (Test et al., 2009). The type and amount of in-service and preservice training individual special educators receive regarding transition vary greatly.

What effect this variance in training/competency has on teacher involvement in the

various components of transition needed to be examined, particularly as these teachers

are increasingly the main agent of the process.

Statement of the Problem

The purpose of this study was to determine the level of involvement of secondary

special education teachers in a Unified School District in five identified components of

the transition planning process for students with specific learning disabilities (SLD) with

an Individual Education Plan: 1) Assessment and data gathering, 2) Collaboration on goal

setting, 3) Incorporating transition-related curriculum, 4) Coordination and collaboration

with outside agencies, and 5) Job training and supervision for students. The secondary

purpose of the study was to determine what correlation, if any, these teachers’ pre-service

and in-service training had with their level of involvement in each category. To frame

the research and analysis, three questions were considered:

1. What are teachers’ perceived roles and responsibilities in the transition

process for students on their caseload? Which parts of the transition process

are they most involved in?

3

2. Does pre-service training affect how involved teachers are in transition-related

competencies? If so, which components?

3. Does in-service training affect how involved teachers are in transition-related

competencies? If so, which components?

Definition of Terms

Individual Education Plan

For the purposes of this study, the term “Individual Education Plan” (IEP) refers

to the legally mandated plan for educational and other support services in grades

K-12 for a student qualifying with one or more disabilities.

Secondary Special Educator

For the purposes of this study, the term “Secondary Special Educator” refers to a

Secondary (middle or high school) teacher with a Mild/Moderate Educational

Specialist Credential. These teachers are responsible for the planning,

monitoring, and implementation of one or more students’ Individual Education

Plans.

Students with Disabilities

For the purposes of this study, the term “Students with Disabilities” refers to

secondary students who have received Special Education Services through an

Individual Education Plan, which is legally mandated to include a Transition Plan

component. More specifically, these students have one or more Specific Learning

4

Disabilities. According to IDEA (2004), Specific Learning Disability involves a

“disorder in 1 or more of the basic psychological processes involved in

understanding or in using language, spoken or written, which disorder may

manifest itself in the imperfect ability to listen, think, speak, read, write, spell, or

do mathematical calculations” (§300.8(c)(10))

This population may include students with cognitive delays, visual, auditory, or

sensory-motor processing deficits.

Transition Plan

For the purposes of this study, the term “Transition Plan” refers to the part of a

Student’s Individual Education Plan addressing the set of coordinated activities

that lead to successful secondary completion and achievement of goals in the

areas of continuing education, employment, and community living.

Significance of the Study

This study was selected to determine which areas of the transition planning

process special education teachers at the secondary level in a Unified School District are

least involved in and, secondly, whether this correlates with their amount of training in

those areas. This study created new knowledge to be used by this Unified School District

and could also possibly be generalized to other secondary schools in California, and even

nationally. This study reveals which components of transition planning secondary special

educators feel less competent and/or involved in. From that information, educational

5

leaders in the district can design in-service training to potentially increase competency in

areas of transition that currently lack high levels of special educator involvement.

Ideally, the increased competency would lead to increased levels of participation in those

areas of the transition process. Ultimately, the goal of this study was to gather data to

help design effective transition services for students with learning disabilities so they

might reach their highest potential after graduating secondary school.

Organization of the Remainder of the Study

This study is organized into five chapters. Following this section, Chapter 2 is a

review of related literature discussing post-secondary outcomes for students with

disabilities as well as evidence-based components of, special educators’ perceived

competencies and involvement in, and the role of leadership and administration in

Transition Planning. Chapter 3 explains the research methodology, data collection, and

analysis processes. The results of the survey are highlighted in Chapter 4, and Chapter 5

provides a summary of the study along with conclusions, recommendations, and

implications for future research.

6

Chapter 2

REVIEW OF THE RELATED LITERATURE

Introduction

Since the federal definition of learning disabilities was introduced in 1975, it has

represented the largest population of students served with special education services.

According to the U.S. Department of Education (DOE), Office of Special Education

Programs, Data Analysis System (2011), the number of students classified and served

under the category of Specific Learning Disability in the United States between the ages

of 14 and 21 is 1,106,296. Additionally, during the 2002-2003 school year in California,

of the 609,182 students with disabilities served under IDEA, 340,579 of those students

were identified with an SLD. Overall, SLD now constitutes the largest group of students

identified with a disability in public schools (DOE, 2000). This population of students

will, after many years of support services, be expected to graduate secondary and move

into adult life. As students with SLDs prepare for their transition to post-secondary life,

anxiety and feelings of uncertainty about the future arise.

Anxiety happens when such students are not adequately informed about and

prepared for post-secondary education, employment, and independent living (Furney,

Hasazi, & Destefano, 1997). It was formerly believed by educators and legislators that

students with learning disabilities would be able to become successful, productive

members of society without the transitional support provided for students with more

7

severe disabilities (Bassett & Smith, 1996). Fortunately, transition plans for learningdisabled students are now legally required as part of their Individual Education Plan.

Ideally, a well-designed and executed transition plan will prepare students for completion

and graduation from secondary school to enter into a productive post-secondary life.

In 1990, the United States Congress amended Public Law 94-142 to what is now

known as the Individuals with Disabilities Act or IDEA (Public Law 101-476). In June

of 1997, IDEA was reauthorized (Public Law 105-17). One of the major components of

the reauthorization of IDEA was to include transitional services in the Individualized

Education Plan (IEP) for disabled students by the age of 16 or as early as age 14 when

deemed necessary (National Information Center for Children and Youth with Disabilities

[NICHCY], 1993). Transitional services are defined as

those coordinated activities for students with disabilities that are designed within

an outcome-oriented process that promotes movement from school to post-school

activities, including postsecondary education, vocational training, integrated

employment (including supported employment); continuing and adult education;

adult services; independent living; or community participation. Transitional

services must be based on the individual student’s needs and take into account the

student’s preferences and interests. They must include instruction; related

services; community experiences; the development of employment and other

postschool adult living objectives; and, when appropriate, the acquisition of daily

8

living skills and functional vocational evaluation. (Katsiyannis & Zhang, 2001, p.

40)

The National Joint Committee on Learning Disabilities (NJCLD; 1994) stated:

“Comprehensive transition planning needs to address several domains including

education, employment, personal responsibility, relationships, home and family leisure

pursuits, community involvement, and physical and emotional health” (p. 71). The

purpose of including transitional services was to directly address the troubling postsecondary outcomes for students with disabilities. By 1997, 44 states had received

federal special education transition grants and discretionary funding to improve the

availability of, access to, and quality of school-to-work transition services (Katsiyannis &

Zhang, 2001).

The levels of successful transition are difficult to quantify because each student

has different needs, disabilities, and abilities. However, despite these differences, a

successful transition plan will help each student with disabilities toward achieving the

highest potential level of post-secondary life success. Special education teachers must

have knowledge of and participate in the wide array of components involved in a

transition plan. This is so because they are increasingly responsible for the planning,

initiating, and monitoring of these legally mandated plans that will lead their students

with learning disabilities to the aforementioned post-secondary success (Li, Bassett, &

Hutchinson, 2009). This literature review surrounding the topic of the Transition

Planning process for students with Learning Disabilities discusses four subtopics: the

9

current status of post-secondary outcomes for students with mild to moderate disabilities

(emphasis on Specific Learning Disabilities), the evidence-based components of a

successful transition plan for these students, secondary special educators’ perceived

competencies and involvement in the transition planning process, and finally the role of

the administration and leadership in supporting the transition process and secondary

special educators.

Post-secondary Outcomes for Students with Disabilities

The purpose and goal of a Transition Plan is to help students with disabilities

achieve success in finding and keeping good jobs, living independently in their own

homes, obtaining further education, and leading ultimately satisfying post-secondary

lives (Beard, 1991). Unfortunately, the outcomes for many students with disabilities do

not reflect these goals despite their having average to above-average intelligence levels

(National Longitudinal Transition Study-2 [NLTS2], 2003). In light of the discrepancy in

the post-secondary outcomes between students with learning disabilities and their nondisabled peers, it is critical that the Transition Plan within the IEP be thorough and

effective.

Graduating from secondary school and pursuing adult life beyond it is a

significant milestone in an individual’s life. Unfortunately, students with disabilities

have a much lower success rate at this transition than do their non-disabled peers (Test et

al., 2009). Data from a representative national sample indicate the dropout rate for all

10

students was between 4% and 10.3% (NCES, 2003, 2004), while the National

Longitudinal Transition Study-2 (2005) reported students with disabilities did not

complete school at a rate of 28%. Research indicates students who do not graduate have

higher rates of unemployment or underemployment and experience higher rates of

unexpected parenthood drug use (Swaim, Beauvis, Chavez, & Oetting, 1996).

Beyond secondary graduation, Individual Transition Plans set forth a path for

pursuing higher educational goals based on student preferences and interests (Thoma,

Baker, & Saddler, 2002). However, according to the NCES (2004), students with

disabilities are not pursuing or obtaining post-secondary education at the same rate as

their non-disabled peers. Research findings suggest that, despite their average or aboveaverage intelligence, fewer students with learning disabilities attend either two- or fouryear colleges (NJCLD, 1994). The NJCLD stated, “Many learning-disabled students are

not encouraged, assisted, or prepared for post-secondary education” (p. 69). Of those

students with mild to moderate disabilities that do go on to college, studies suggest many

experience difficulty persisting through postsecondary programs to completion. In a

study titled “The Beginning Postsecondary Students Longitudinal Study,” a

representative sample of students, with and without disabilities was followed as they

began college during the 1989-1990 school year. Six years later, it was found that the

overall percentage of students who persisted through to attain their degree or who were

still enrolled was approximately 43% for students with disabilities but approximately

11

64% for their nondisabled peers (DOE, 2000). Students with disabilities who go on to

pursue post-secondary education face unique challenges.

Although they have the capacity to succeed, there are many challenges for

students with disabilities who enroll in college after high school in addition to their

learning deficits (Cummings, Maddux, & Casey, 2000). First, students sometimes

discover their post-secondary educational program does not meet the career goals

considered in their IEP Transition plan (Field, 1996; Levinson, 1998). A second obstacle

is that these students often deny problems with learning and/or do not seek the

accommodations they need to be successful in college (Field, 1996). Students with

learning disabilities may do this in order to distance themselves from the Special

Education label they carried throughout their school years, or because they are illequipped with self-advocacy skills to ask for the necessary accommodations. The latter

point is particularly correlated with larger class sizes and the instructor-to-student ratio

and contact level drastically differing from the secondary school support these students

may have been accustomed to (Lerner, 1997).

Further, the differences between secondary and post-secondary learning

experiences contribute to the lower rate of persistence for students with Learning

Disabilities (Lerner, 1997). While in high school, students are typically given short-term

assignments with frequent grading and feedback. In contrast, college classes and

professors often assign long-term projects and do not give frequent progress evaluation

(Lerner, 1997). Many colleges and institutions provide support services for students with

12

learning disabilities. Services such as tutors, readers, note-takers, class registration

assistance and adaptive equipment and technology are available; however the

identification of students needing these accommodations is largely left up to parent- or

self-referrals prior to admission (DOE, 2000; Gajar, 1992). The combination of lack of

self-advocacy skills needed to ask for appropriate accommodations, infrequent and

limited contact with professors, and the drastic differences in structure between

secondary and post-secondary education contribute to many students with disabilities

dropping out of their post-secondary education experience (Cummings et al., 2000).

In addition to lower high school graduation rates and enrollment and persistence

in college, research findings regarding the post-secondary employment of students with

learning disabilities indicate further discrepancy when compared to their non-learningdisabled counterparts. Research indicates while most of these students hold jobs as adults

at near the same rate as non-learning-disabled peers, most work on a part-time basis, at an

entry-level position, and for minimum wage (Sitlington, Frank, & Carson, 1993). Studies

have also indicated people with specific learning disabilities are less satisfied socially, are

earning at a lower income bracket, and are more dependent on family members

(Rojewski, 1994). Given their less than successful rates of completion for secondary

school and their difficulties in transition to productive, satisfying adult life, there has

been much research conducted to determine the elements of design, implementation, and

monitoring of an effective Transition Plan for students with mild to moderate learning

disabilities.

13

Evidence-based Components of Transition Planning

Although the IDEA requirements for a Transition Plan aim to facilitate movement

from school to post-school activities and education, simply developing a Transition Plan

does not necessarily translate into students gaining long-term employment or pursuing

post-secondary education (Wehman, 1992). The Transition Plan must be structured upon

evidence-based practices in order to be effective. According to research, the potentially

complex Transition Plan can be broken down into several areas of focus. Each of these

components must be addressed to create a comprehensive and effective Transition Plan

for a student with mild to moderate learning disabilities. The National Secondary

Transition Technical Assistance Center (NSTTAC) identified evidence-based transition

practices according to research and experimental studies (Kohler, 1996). From their

research, NSTTAC organized the transition practices into taxonomy with five broad

areas: student-focused planning, student development, interagency collaboration, family

involvement, and program structure. Each of these five categories was broken down

further into subcategories of specific activities as well as descriptions of particular

transition practices that could be utilized by educators working with students with

disabilities. The purpose in identifying these practices and categories was to then create

an online database to collect, document, and share transition practices aligned with these

evidence-based categories as well as provide ideas and tips to other special educators and

service personnel (Kohler, 1996). Each of these five broad areas requires much

involvement from the Special Educator/IEP case manager.

14

The first area in the taxonomy of evidence-based transition practices, studentfocused planning, involves the subcomponent of collaborating with the student on goal

setting (Kohler, 1996). As mentioned in the outcomes portion of this review of related

literature, lack of skills in self-advocacy is one of the primary reasons for students with

learning disabilities’ failure to persist through post-secondary education. However,

research has shown when students are involved in the planning of their own transitions

and are engaged in self-advocacy activities early on in secondary school, they take more

active responsibility for their post-secondary school lives (Levine, Marder, & Wagner,

2004). Primary examples of the skills and knowledge students stand to gain from being

participants in developing their Transition Plan and goals are, “1) The ability to assess

themselves, including their skills and abilities, and needs associated with their disability;

2) Awareness of the accommodations they need; 3) Knowledge of their legal rights to

these accommodations; and 4) Self-advocacy skills necessary to express their needs in

educational, work, and community settings” (Martin, Huber Marshall, & Depry, 2001;

Wandry & Repetto, 1993). Student involvement in his or her own Transition Planning

and goal setting is a legal component to an IEP, and also critical to the plan’s

effectiveness.

Another component of student-focused planning is using and incorporating

assessment data as part of the Transition Plan process. The regulations of IDEA state that

when a student chooses not to attend the IEP meeting, the school must “take other steps

to ensure that the student’s preferences and interests are considered” in regard to their

15

long-range goals for education, involvement in their community, employment, and other

post school opportunities [34 CFR 300.344 (c)(2)] (IDEA, 2004). The responsibility to

provide evidence that a student’s preferences and interests were considered in the

planning process could be fulfilled with a standardized transition assessment procedure

(Clark, 1996). According to Clark (1996), transition goals and objectives for a student

“should come directly from transition-referenced assessment” and not just the typical

academic-based assessments given in preparation for an IEP meeting (p. 82). Clark also

posited transition-related assessments are unique in that they call student and parent

attention to real-life issues and ideas that an academic assessment cannot.

Students and parents who tend to approach life without any hope of changing

what is happening to them (now or in the future) will see the school and the

educational process in a very different way when they are included in the

assessment, planning, and implementation of an IEP based on a transition/

outcomes approach. (Clark, 1996, p. 84)

Knowledge of a student’s needs, preferences, and interests for their future should

come out of an assessment and assessment process that focuses on aspects of a student’s

post-secondary life required by IDEA (Clark, 1996). Transition-related assessments can

include paper or online surveys and checklists regarding student interests used by the

classroom teacher or Special Educator. These data could then be incorporated into the

IEP and transition goals. Clark (1996) also claimed if the assessment process of an IEP

does not include elements of transition going beyond school progress and academic

16

achievement, a student will be less likely to internalize the plan. In addition, the

transition assessment data gathered serve to document two legal components of an IEP:

student participation in the process, and present levels of performance (Clark, 1996).

Using assessment to drive the Transition Plan and IEP is critical to maintaining a studentfocused and effective plan.

Related to student-focused planning is the second component of an evidencebased Transition Plan, student development. IDEA emphasizes student involvement and

progress in the general education curriculum (IDEA, 2004). This emphasis necessitates

aligning academic curriculum with individual post-secondary school goals in the

Transition Plan. Student development requires the special educator to embed transitionrelated curriculum into his or her own lessons, or to collaborate with the general

education teacher to do the same (Kohler, 1996). The curriculum content should ideally

work in conjunction with the student’s transition goals (Kohler, 1996). Bassett and

Kochhar-Bryan (2002) identified the necessary components of a blended program of

transition-focused yet standards-based curriculum: “continuous, systematic planning,

coordination, and decision making to define and achieve postsecondary goals; curriculum

options or pathways; academic, career-technical, and community-based learning; multiple

outcome domains and measures; and appropriate aids and supports (opportunities)”

(§300.320(b)). As of 2002, 28 states were using academic as well as career and

vocational standards to assist students in generalizing the skills they learn in school to the

real world they will encounter beyond it (Williams, 2002). Incorporating vocational

17

curriculum into the core content and thus making connections between school and the

world beyond it promotes students’ chances at a successful transition from secondary to

post-secondary life.

The next broad area of effective transition practice is interagency collaboration.

This area requires the Special Educator to work with professionals from outside agencies

and other district service providers to set transition goals and give students job experience

moving them toward those goals (Kohler, 1996). IDEA 1997 stated an IEP must include,

“a statement of needed transition services for the child, including, when appropriate, a

statement of the interagency responsibilities or any needed linkages” (Katsiyannis &

Zhang, 2001, p. 39). Although the 2004 reauthorization does not include this statement,

interagency collaboration on student transition goals is still an expectation: as stated in

IDEA 2004, the IEP will include the “projected date for the beginning of services and

modifications, the anticipated frequency, location and duration of those services”

[(D)(1)(A)(VII). “If a participating agency fails to provide the transition services

described in the IEP, the local educational agency shall reconvene the IEP team to

identify strategies to meet the transition objectives for the child set out in the IEP”

(IDEA, 2004, §300.324 (c)(1))

The Special Education teacher and case manager is the primary liaison between these

outside agencies, such as higher education programs, job placements, and the student’s

transition goals (Bassett & Kochhar-Bryant, 2006).

18

At times, the special educator also acts as liaison between a student’s parent(s)

and outside agencies or other service providers. Together with other forms of parental

involvement, this is the fourth component critical to an evidence-based, effective

Transition Plan (Kohler, 1996). IDEA states parents will receive notification when

transition planning will be part of an IEP meeting (IDEA, 2004). However, ideally the

student and parent will be involved in transition services and planning in a more

collaborative manner. The parents, guardians,

and advocates are needed to provide their perspective on the student’s needs,

preferences, and interests. It may also be important to know the parents’,

guardians’, or advocates’ own views of what they prefer for the student,

especially when there is a discrepancy between their views and the student’s or

school’s views. (Clark, 1996, p. 87)

Lastly, the overall IEP program structure and transition planning greatly hinders

or enhances the success of the plan (Kohler, 1996). NJCLD (1990) included in its list of

troubles related to preparing students with learning disabilities for future endeavors the

following statement: “Coordinated planning is lacking for students with learning

disabilities as they make transitions from home to school to work, across levels of

schooling, and among educational settings” (p. 100). The NJCLD (1990) also proposes

the establishment of “a system-wide plan for helping students with learning disabilities to

make transitions from home to school to work and life in the community” (p. 100). The

NJCLD's position makes clear that providing thoroughly designed, systematic Transition

19

Plans and services is critical in aiding students with mild to moderate disabilities to

prepare for post-secondary life. It is necessary for the Special Educator acting as

transition planner to maintain a comprehensible system to manage the Transition Plan:

from goal setting on the IEP in collaboration with the student, parent and outside

agencies, to implementing transition curriculum into a student’s educational experience,

to monitoring the success and/or need for revision of the plan.

Special Educators’ Perceived Competencies and Involvement in Transition

According to the research of Blackorby and Wagner (1996), even with support

systems such as a Transition Plan, students with disabilities tend to realize fewer positive

post-secondary outcomes: they experience high dropout rates (Blackorby & Wagner,

1996), have lower participation in postsecondary education, lower employment rates,

lower earning power, and lower satisfaction with their adult lives than students in the

general population (Blackorby & Wagner, 1996). Benz, Lindstrom, and Yovanoff (2000)

found career-related work experience and the completion of student-identified transition

goals were highly associated with improved graduation and employment outcomes.

Secondary special educators currently have the additional responsibility of creating,

implementing, and monitoring the Transition Plan mandated by IDEA 2004, which may

improve the post-secondary outcomes of their students with learning disabilities. With

these new responsibilities come the questions of what type of competencies do secondary

special educators require to meet the new responsibilities of becoming transition

20

planners, as well as how teacher preparation programs and those in charge of ongoing

professional development have responded to these mandates.

To implement each component of an effective and comprehensive Transition Plan

for a student, special educators must receive training before or during their tenure. A

study by Conderman and Katsiyannis (2002) revealed secondary special education

teachers are largely responsible for providing a wide variety of transition services,

including vocational instruction, transition-related activities in the classroom,

coordination of work experiences, and maintenance of community contacts with other

who support transition outcomes. The unique responsibilities required of secondary

special educators as related to transition planning would require unique pre-service and

ongoing in-service training in order to meet these additional job demands (Conderman &

Katsiyannis, 2002). However, in a nationwide study of special education teacher

preparation programs, McKenzie (1995) found little more than 20% of the programs

required separate training for secondary special educators versus elementary special

educators. Research by Wasburn-Moses (2006) regarding high school special education

teachers’ assessment of their involvement in transition planning and effectiveness of their

teacher preparation programs resulted in similar findings. Of teachers surveyed in this

research, nearly half reported they were working on improving services in transition

planning and needed more training for themselves and their staff, as well as more time

(Wasburn-Moses, 2006).

21

With the myriad additional roles and responsibilities they hold as transition

planner and servicer, teachers should expect to receive training in their teacher education

programs or through targeted in-service trainings. However, special educators often fail

to participate in many aspects of transition because they have not received adequate

education in delivering transition services in their teacher training programs. Findings

from a national survey of 573 special education teacher preparation programs showed

less than half these programs addressed transition standards (Anderson et al., 2003).

Additionally, only 45% of these programs offered a course devoted solely to transition.

The instructors of the programs reported transition competencies were embedded within

other content, but research has shown embedded content does not allow for adequate

focus or coverage of the content (Anderson et al., 2003). Teachers’ perceived lack of

competency in some areas of transition negatively correlates with their involvement in

those areas of the Transition Plan process. Research shows special education teachers

consider the competencies they have received the most training in the most important, yet

teachers do not always receive adequate training in all components of an effective

Transition Plan (Blanchett, 2001). In conclusion, if teachers are not adequately prepared

and do not perceive themselves as knowledgeable in a particular area of service delivery,

they are less likely to be involved.

22

The Role of Leadership and Administration in Transition Planning

Administrators are influential in ensuring achievement for all students, including

those with disabilities. Their instructional leadership, support, and guidance help general

and special education teachers and staff ensure all students meet established outcomes

(Katsiyannis & Zhang, 2001). The Individual Education Plan, which includes the

Transition Plan from age 16, is an integral part of meeting the needs of students with

disabilities and a process school administrators must be aware of and take part in (Wright

& Wright, 1999). The IEP is the topic of communication between the special education

teacher, general education teacher, parent, student, and school administrator regarding

how a school plans to meet the legal requirements of IDEA 2004 for a particular student.

Principals or the representative designee signing the IEP must know what the plan

contains to ensure it is both legally sound and implemented with integrity in order to

promote success for this population of students on their campus (Armenta & Beckers,

2006).

The intersection between leadership and the Transition Plan component of a

student’s IEP is critical. School principals and district special education administrators

are a very important part of the IEP team, and ultimately responsible for ensuring

students are receiving an Individualized Education Program that is meaningful and

effective (Yell, Katsiyannis, & Bradley, 2003). The members of an IEP team must

include the parent/s (biological, guardians, or surrogate), the student’s special education

teacher, the student’s regular education teacher, the student, and a representative of the

23

Local Educational Agency (LEP) (Yell et al., 2003). IDEA 2004 requires the

Representative of the LEP be qualified to provide or supervise the provision of special

education services and to ensure that the services put forth in the IEP are provided

appropriately (IDEA, 2004). This individual must also be able to commit school

resources (Yell et al., 2003). The principal of a school is often the staff member onsite

who qualifies to serve in this role. It stands to reason that the oversight of a principal

knowledgeable in Individual Education Plans could enhance the efficacy of the

Transition Plan component by providing support and financial backing, as well as

ensuring all components of an effective plan are included in the planning process.

School administrators can promote many of the critical components of a

Transition Plan through their leadership: transition planning, student active participation,

family involvement, and interagency collaboration. Katsiyannis and Zhang (2001) list

five critical recommendations for administrators to encourage an IEP team to do in order

to promote successful transition planning for students with disabilities: design transition

services according to student needs and interests and ensure that their family input is

incorporated, utilize individualized transition assessment to identify student strengths and

weaknesses and plan according to the strengths, identify and document specific transition

outcomes that reflect the student’s strengths and preferences, determine the supports

needed for the student to reach the identified goals, and lastly, never discount student and

parent input as unrealistic; the student will lose interest if the plan is not based around

their needs and interests (Katsiyannis & Zhang, 2001).

24

Not only is it required by law, but a student’s active participation and input

toward a Transition Plan is paramount to success, and they should therefore be at the

center of the transition process (Armenta & Beckers, 2006). To promote student

participation in the process, a school administrator should first of all enforce the

requirement for student attendance at the IEP meeting (Katsiyannis & Zhang, 2001).

Teachers should be prompted by their principal to prepare the student in advance

particularly in regard to the Transition Plan component and to take a leadership role at

their own meeting (Katsiyannis & Zhang, 2001). A principal can also promote a

student’s family involvement by encouraging the IEP team to invite participation and

listen to them and their unique concerns, expectations and desires for their child at the

IEP meeting (Katsiyannis & Zhang, 2001). Parent or guardian involvement is one of the

best predictors of postsecondary success for young adults with mild to moderate

disabilities (Clark, 1996); therefore, administrators should encourage the IEP team to

make them integral participants.

Effective Transition Plans require strong interagency collaboration, which

eliminates gaps in service and offers more seamless and holistic planning and service

delivery (Kohler 1996). A school leader can promote better interagency collaboration by

providing time for special education teachers to meet with the district’s transition

specialist to allow for time to discuss available resources and to identify the

representatives who will be needed for a particular student’s Transition Plan and IEP

meeting (Katsiyannis & Zhang, 2001). Special education teachers must clearly

25

understand the different roles and responsibilities of agencies with whom they may work

in collaboration as part of a student’s Transition Plan to determine whom to contact and

invite to the IEP meeting (Basset & Kochhar-Bryant, 2006). The administrator of a

school should encourage more seamless collaboration with other agencies by providing

time to meet with the district’s expert in transition who can assist secondary special

educators with identifying the critical outside agencies and representatives (Katsiyannis

& Zhang, 2001).

Not only can they provide necessary oversight and support for the IEP team, but

additionally an administrator knowledgeable in special education laws and involved in

the implementation and monitoring of IEPs can save their school district from costly

litigation (Yell et al., 2003). IDEA mandates the special education process include

referral, evaluation, qualification, development of the IEP, and annual review of the IEP.

Through each part of the process, if strict adherence to procedural requirements is not

upheld, errors may be made that render the plan ruled inappropriate in due process

hearing (Bateman & Linden, 1998). Research shows most hearings school districts lose

are the result of such procedural mistakes in the IEP process (Yell, 1998). In conclusion,

by becoming involved in the IEP process, a school leader can not only ensure the team

develops legally sound and educationally appropriate IEPs to promote success in

secondary school and beyond, but also save the school district from expensive due

process hearings (Yell, 1998). Administrators play a vital role in ensuring all students,

including those with disabilities, succeed (Katsiyannis & Zhang, 2001).

26

Rationale for the Study

Students with learning disabilities continue to have less than successful postsecondary outcomes (high school graduation, college, employment, etc…) as compared

to their general education peers (Test et al., 2009). These students need guidance

throughout their middle and high school years to put them on a trajectory toward

increased chance of success. The secondary special education teachers who guide these

youth through school and into their futures must have adequate training in the

components that research has shown to be essential for a successful, effective and legally

sound Transition Plan. To coordinate and provide tailored in-service trainings to

compensate for any gaps in teachers’ pre-service training experience, School Leaders

must first know which components show the least Secondary Special Educator

preparedness and participation.

Summary

Students with disabilities do not graduate from secondary, attain post-secondary

education, or earn salaries at the same rate/level as their non-disabled peers, despite their

average to above-average intelligence (Sitlington et al., 1993). For a student with a

specific learning disability to experience optimal success in their future, an effective

Transition Plan must be designed, implemented, and monitored, more often than not, by

the special educator who manages their case. According to IDEA (Public Law 101-476),

this Transition Plan is a legally mandated part of an Individualized Education Plan for a

27

student with a disability. For a Transition plan to be effective, it must have the following

five components: assessment and data gathering, collaboration on goal setting,

incorporating transition related curriculum, coordination, and collaboration with outside

agencies, and job training and supervision for students. The effectiveness of a Transition

Plan is further increased by perceived teacher competency and preparation in each of the

five components. The competency and preparedness leads to greater participation in the

transition planning process.

The implication of this literature review on the study is four-fold. First, there is a

need to bridge the graduation and post-secondary achievement gap between students with

specific learning disabilities and their non-disabled peers. Second, an effectively

designed and implemented Transition Plan can lead to optimal achievement. Third,

special education teachers must be adequately prepared in each of the components of the

transition planning process if they are to be expected to be effective agents in enacting

and seeing the plans through. Finally, school administrators can promote better postsecondary outcomes for their students with Learning Disabilities by being knowledgeable

and active IEP team participants and overseers of the special education process. This will

help ensure the student with Learning Disabilities receives appropriate services and the

Transition Plan developed by the team is legally sound and effectively implemented.

28

Chapter 3

METHODOLOGY

Population and Sample

Participants of this study were chosen by cluster sampling to be representative of

secondary special education teachers in an unnamed Unified School District. There were

nine middle schools and nine high schools in this population. Survey questionnaires were

distributed only to secondary special education teachers within this population,

specifically from one middle school. At this school site, five special educators have

students on their caseload designated with mild to moderate disabilities, an Individual

Education Plan, and thus an Individual Transition Plan.

Design of the Study

Data Collection

Data collection was begun by sending the Transition Involvement and

Competency Questionnaire to all members of the target sample, secondary special

education teachers at a particular middle school (see Appendix). Five teachers in total

were given the questionnaires; all were returned. The questionnaires were sent to the

teachers through the district email server along with a note providing the respondents

with a brief explanation of the purpose of the study and an assurance their participation

was voluntary and the results would be confidential and available for their review if

29

requested. Email addresses were obtained by searching the database for each name on

the list of five teachers who provide services to students with Specific Learning

Disabilities. A hard copy of the survey was also placed in their mailboxes at the school

site. Participants were informed the survey would take approximately 15-20 minutes to

complete. The researcher reviewed all questionnaires submitted via email or hard copy.

Four were returned in hard copy format and one electronically. The submitted

questionnaires were kept anonymous.

Instrumentation

The questionnaire contained 35 total items. The first part asked secondary special

educators to rate their levels of involvement in five identified components of a Transition

Plan: assessment and data gathering, collaboration on goal setting, incorporating

transition-related curriculum, coordination and collaboration with outside agencies, and

job training and supervision for students. Each component had two to three correlating

questions. The frequency continuum was Never, Hardly Ever, Occasionally, With Some

Frequency, With Very High Frequency. These were given values of 0-5, respectively, for

purposes of analyzing the data collected.

The second portion of the questionnaire asked secondary special educators

questions about their pre-service and in-service training regarding transition. There were

two to three questions correlating to teacher competency in each of the five identified

components of a Transition Plan. The quantitative continuum was None, Very Little,

30

Some, Adequate, A Lot. These were given values of 0-5, respectively, for purposes of

analyzing the data collected.

Data Analysis Procedures

All five questionnaires were returned from teachers, giving a 100% return rate.

Frequencies and descriptive statistics were taken based on the data collected from the

questionnaires. Statistically relevant correlations regarding involvement in the five

identified components of transition and the amount of pre-service/in-service training

teachers received were considered. Trends were identified based on the data regarding

secondary special educators’ level of preparedness and involvement in the five

components of transition.

Limitation of Study

The research had some limitations. First, the research study focused on secondary

special education teachers currently working at one middle school in a particular school

district. The results of this study may not be reflective of the training, involvement and

preparedness in Transition Planning of all secondary special education teachers in the

district or those working in other districts.

Second, the secondary special educators surveyed did not include high school

level teachers. High school level teachers may receive more in-service training regarding

Transition Planning as the vast majority of their caseload students are at or above the age

at which a Transition Plan is legally required as part of the I.E.P. (16). Had high school

31

special education teachers of students with learning disabilities been surveyed, the inservice training portion of the questionnaire may have yielded different results.

Lastly, distributing the questionnaire to a sample population from the school site

at which the researcher also works and has daily contact with may have led to selfreporting bias. Self-reporting bias occurs because the “research participants want to

respond in a way that makes them look as good as possible. Thus they tend to underreport behaviors deemed inappropriate by researchers or other observers, and they tend to

over-report behaviors viewed as appropriate” (Donaldson & Grant-Vallone, 2002, p.246).

Although the participants were assured that the results would be kept confidential, the

thought that the researcher may review could have led to this bias. Distributing the

questionnaire to a sample from another school site may have lessened the possibility for it

to occur.

32

Chapter 4

DATA ANALYSIS

The first portion of the Involvement and Training in Transition questionnaire

contained questions 1-11, aimed at determining the frequency with which secondary

mild/moderate educational specialists participated in the five identified components of an

effective Transition Plan: assessment and data gathering, collaboration on goal setting,

incorporating transition-related curriculum, coordination and collaboration with outside

agencies, and job training and supervision for students. The frequency continuum was

Never, Hardly Ever, Occasionally, With Some Frequency, With Very High Frequency.

These descriptors were given values of 0-5, respectively. For data analysis purposes, two

to three questions from this section were grouped together under the umbrella for each of

the five categories of an effective Transition Plan. This data analysis is shown in Table

A, which indicates responses to the questions with regards to frequency of involvement.

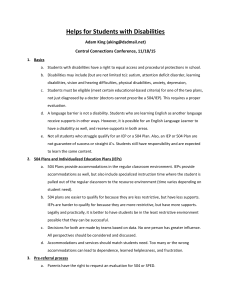

Questions 1 and 2 were categorized together in the data analysis (see Table 1) as a

subsection to mild/moderate educational specialist involvement in transition planning

titled “Frequency of Gathering Assessment Data.” Question 1 asked: How often do you

collect data which add to one of your student’s Transition Plans? Question 2 asked: How

often do you use assessment tools to gather data toward a student’s Transition Plan? As

shown in Table 1, 30% of responses indicated respondents never being involved in

gathering assessment data and or using assessment tools, 20% indicated hardly ever or

33

occasionally, 10% occasionally, 30% responded with some frequency and 10% reported

with very high frequency. These data reveal a divide among respondents; several of the

educators surveyed (40% of responses) are frequently involved in gathering assessment

data to add to a Transition Plan, while half the responses indicated rare involvement in

using assessment tools to gather data for a Transition Plan. Forty percent reported some

to high frequency, which indicates “assessment data” is one of the two greatest areas of

teacher involvement of the five categories of transition planning.

Table 1

Secondary Mild/Moderate Educational Specialist Involvement

Questions 3-5 were categorized together in the data analysis shown in Table 1 as

teacher “frequency of collaborating on goal setting.” Question 3 asked: How often do

34

you collaborate with parents in goal setting for individual Transition Plans? Question 4

asked: How often do you collaborate with students in goal setting for individual

Transition Plans? Question 4 asked: How often do you collaborate with other service

providers or agencies in goal setting for individual Transition Plans? As shown in Table

1, over 50% of the responses indicated never or hardly ever with regards to collaborating

on goal setting. Thirteen and three-tenths percent of the responses indicated occasional

collaborating on goal setting. Twenty percent of responses indicated with some

frequency and 13% with very high frequency for involvement in gathering assessment

data and/or using assessment tools. Over 50% of responses indicate occasional to high

frequency involvement in goal setting; however the other half of the responses indicated

lack of involvement. These data reveal the respondents’ frequency of involvement in

collaborating with parents, students, and outside service providers and agencies in goal

setting ranges across the spectrum from never to very frequently.

Questions 6 and 7 were grouped together in the data analysis shown in Table 1 as

teacher “frequency of incorporating transition curriculum” as part of the Transition

Planning and implementation process. Question 6 asked: How often do you incorporate

transition-related curriculum into your classroom instruction? Question 7 asked: How

often do you select curriculum content in conjunction with post-secondary goals (i.e.

higher education, employment, etc.)? The data in Table 1 show 30% of responses never

being involved in this component, 10% hardly ever, 30% occasionally, none with some

frequency, and 30% with very high frequency. In summary, 60% of responses indicate

35

occasional to high frequency of involvement in this component, which is the greatest

involvement rate of all surveyed categories. At the same time, at 30%, this category also

has the highest percentage of responses indicating respondents never involved in the

component.

Questions 8 and 9 were grouped together in the data analysis shown in Table 1 as

teacher “frequency of working with outside agencies” as part of the transition planning

and implementation process. Question 8 asked: How often do you work with

professionals from outside agencies? Question 9 asked: How often do you serve as a

liaison between parents and other agencies? Twenty percent of responses indicated this

was never done in the respondent’s practice, 30% hardly ever, 30% occasionally, 20%

with some frequency, and 0% with very high frequency. Responses regarding

involvement in working with outside agencies in the transition planning process are

spread on a spectrum of never to with some frequency.

Questions 10 and 11 were grouped together in the data analysis shown in Table 1

as teacher “frequency of employment training” as part of the transition planning and

implementation process. Question 10 asked: How often do you supervise students on the

job? Question 11 asked: How often do you incorporate curriculum or content related to

post-secondary employment? Sixty percent, the greatest single descriptor response,

responded never with regard to involvement in employment training. Zero percent

reported hardly ever, occasionally, or with some frequency. Forty percent of responses

indicated involvement at high frequency, indicating that “employment training” is one of

36

the two greatest areas of teacher involvement in transition planning, while simultaneously

being the category with the most responses indicating never being involved. The data

indicate a sharp divide between educators involved and uninvolved in employment

training.

Based on the data and combined responses for the never and hardly ever

descriptors, the five identified components of an effective Transition Plan can be ranked

in order from least to most Mild/Moderate Educational Specialist involvement as follows:

1) job training and supervision for students (60% of responses indicated never to hardly

ever involved), 2) collaboration on goal setting (53.4% of responses indicated never to

hardly ever involved), both 3) assessment and data gathering and 4) collaboration with

outside agencies (50% of responses indicated never to hardly ever involved), and 5)

incorporating transition-related curriculum (40% of responses indicated never to hardly

ever involved).

The second portion of the Involvement and Training in Transition questionnaire

contained questions 12-23, aimed at determining the amount of pre-service training

secondary mild/moderate educational specialists received in the five identified

components of an effective Transition Plan. Two to three questions correlating to

teacher-perceived competency and preparedness in each of the five identified components

were categorized together for data analysis (see Table 2). The quantitative continuum

was None, Very Little, Some, Adequate, A lot. These were given values of 0-5,

respectively, for purposes of analyzing the data collected. This data analysis is shown in

37

Table 2, which indicates responses to the questions regarding amount of pre-service

training.

Table 2

Secondary Mild/Moderate Educational Specialist Pre-Service Training

Questions 12 and 13 were grouped together in the data analysis shown in Table 2

as “amount of pre-service training: assessment,” which has to do with teachers’

preparedness to utilize assessments and resulting data in transition planning. Question 12

asked: How much pre-service training were you provided in identifying assessments that

could be used in transition planning? Question 13 asked: How much pre-service training

were you provided in incorporating assessment data into Transition Plans? Responses

were 40% none, 40% very little, 20% some, and 0% adequate or a lot. These responses

38

indicate many teachers had little to no pre-service training in utilizing assessments and

assessment data as part of the transition planning process.

Questions 14-17 were categorized together in the data analysis shown in Table 2

as “amount of pre-service training: planning,” which includes collaborating with students

and their parents and outside agencies as part of transition planning. Question 14 asked:

How much pre-service training were you provided in the transition planning process?

Question 15 asked: How much pre-service training were you provided in collaborating

with students as part of the transition planning process? Question 16 asked: How much

pre-service training were you provided in collaborating with parents as part of the

transition planning process? Question 17 asked: How much pre-service training were

you provided in collaborating with outside agencies as part of the transition planning

process? Sixty percent of responses indicated the amount of pre-service training received

on collaborating in transition planning was none, 15% very little, 25% some, and 0%

adequate or a lot. With 75% of responses at very little to none in regards to involvement,

it seems the majority of educators surveyed did not receive adequate training in

collaborative transition planning.

Questions 18 and 19 were grouped together in the data analysis shown in Table 2

as “amount of pre-service training: curriculum” and centered on teacher training in

delivering transition-related curriculum content as part of the transition process.

Question 18 asked: How much pre-service training were you provided in curriculum

content in conjunction with post-secondary goals (i.e., higher education, employment,

39

etc.)? Question 19 asked: How much pre-service training were you provided in

delivering transition related curriculum? The majority of responses (60%) indicated no

pre-service training in this category, 30% very little, 10% some, and 0% adequate to a

lot. With 90% of responses showing very little to no pre-service training, this category is

one of the two that teachers were least prepared in prior to entering the field as special

educators.

Questions 20 and 21 were grouped together in the data analysis shown in Table 2

as “amount of pre-service training: outside agency” and centered on teacher training in

collaborating with outside agencies as part of transition planning and implementation.

Question 20 asked: How much pre-service training were you provided in working with

professionals from outside agencies to add to a student’s Transition Plan? Question 21

asked: How much pre-service training were you provided in being a collaborative liaison

between parents of your students and outside agencies as part of transition? Similar to

the latter categories of assessment and planning, 50% of responses indicated none with

regards to pre-service training in collaborating with outside agencies in transition

planning, 20% very little, 40% some, and 0% adequate to a lot. This category had the

greatest amount of response indicating some pre-service training.

The final two questions of the second portion of the questionnaire, 22 and 23,

were categorized together under the data analysis category of “amount of pre-service

training: employment training” as listed in Table 2. Question 22 asked: How much preservice training were you provided in developing jobs and job training for students’

40

Transition Plans? Question 23 asked: How much pre-service training were you provided

in supervising students on the job? This category had the highest amount of responses

indicating very little to no pre-service training at 70% none and 20% very little. Only

10% of the responses indicated some pre-service training, and 0% adequate to a lot. No

responses indicated adequate to a lot of pre-service training for any of the five identified

categories comprising an effective Transition Plan.

The third and final portion of the Involvement and Training in Transition

questionnaire contained questions 24-35 aimed at determining the amount of in-service

training secondary mild/moderate educational specialists received in the five identified

components of an effective Transition Plan since entering the field. Two to three

questions correlating to teachers’ in-service training in each of the five identified

components were categorized together for data analysis (see Table 3). The quantitative

continuum was None, Very Little, Some, Adequate, A lot. These were given values of 05, respectively, for purposes of analyzing the data collected. This data analysis is shown

in Table 3, which indicates responses to the questions with regards to amount of inservice training respondents had received.

Questions 24 and 25 were grouped together in the data analysis shown in Table 3

as “amount of in-service training: assessment.” Question 24 asked: How much in-service

training were you provided in identifying assessments that could be used in transition

planning? Question 25 asked: How much in-service training were you provided in

incorporating assessment data into Transition Plans? Thirty percent of responses

41

indicated none in regards to in-service training on utilizing assessment, 0% very little or

some, 50% adequate and 20% a lot. The respondents had the most in-service training in

regard to assessment as compared with the other four categories.

Table 3

Secondary Mild/Moderate Educational Specialist In-Service Training

Questions 26-29 were categorized together in the data analysis shown in Table 3

as “amount of in-service training: planning.” Question 26 asked: How much in-service

training were you provided in the transition planning process? Question 27 asked: How

much in-service training were you provided in collaborating with students as part of the

transition planning process? Question 28 asked: How much in-service training were you

provided in collaborating with parents as part of the transition planning process?

Question 29 asked: How much in-service training were you provided in collaborating

42

with outside agencies as part of the transition planning process? Forty percent of

responses indicated none in regards to in-service training on collaborating transition

planning, 0% very little, 10% some, 25% adequate as well as a lot. This category yielded

the second most responses of adequate to a lot of in-service training, at 50% total. At the

same time, 40% of responses indicated no training in parts of collaborative planning. The

data suggest some of the surveyed educators received in-service training in this area,

while others did not.

Questions 30 and 31 were grouped together in the data analysis shown in Table 3

as “amount of in-service training: curriculum.” Question 30 asked: How much in-service

training were you provided in curriculum content in conjunction with post-secondary

goals (i.e., higher education, employment, etc.)? Question 31 asked: How much inservice training were you provided in delivering transition-related curriculum?

Responses were spread through the continuum: 20% none, 20% very little, 40% some,

0% adequate and 20% a lot of training. This category yielded the most responses of

some training. Data suggest educators have varied experiences with in-service training in

regards to transition-related curriculum design and implementation.

Questions 32 and 33 were grouped together in the data analysis shown in Table 3

as “amount of in-service training: outside agency.” Question 32 asked: How much inservice training were you provided in working with professionals from outside agencies

to add to a student’s Transition Plan? Question 33 asked: How much in-service training

were you provided in being a collaborative liaison between parents of your students and

43

outside agencies as part of transition? Seventy percent of the responses indicated no

training in this component. Thirty percent indicated very little. There were zero

responses for some, adequate, or a lot of in-service training. Data strongly suggest

educational specialists surveyed have not received in-service training in collaborating

with outside agencies as a part of transition planning and implementation.

The final two questions of the third portion of the questionnaire, 34 and 35, were

categorized together under the data analysis category of “amount of in-service training:

employment training” as listed in Table 3. Question 34 asked: How much in-service

training were you provided in developing jobs and job training for students’ Transition

Plans? Question 35 asked: How much in-service training were you provided in

supervising students on the job? Along with the outside agency collaboration

component, employment training had 100% of responses indicating very little to no preservice training at 70% none and 30% very little. There were no responses indicating

some, adequate, or a lot of pre-service training for employment training. The data

suggest the Mild/Moderate Educational Specialists surveyed have not received adequate

in-service training in this category since entering the field.

When analyzing the combined responses for in-service and pre-service training of

Secondary Mild/Moderate Educational Specialists for each of the five identified

transition components, as shown in Table 4, they can be ranked in order of least to most

overall teacher training and preparedness as follows: 1) job training and supervision for

students (95% of responses indicated none to very little overall training), 2) coordination

44

and collaboration with outside agencies (85% of responses indicated none to very little

overall training), 3) incorporating transition-related curriculum (65% of responses

indicated none to very little overall training), 4) collaboration on goal setting and