Introduction to Corpus Linguistics

advertisement

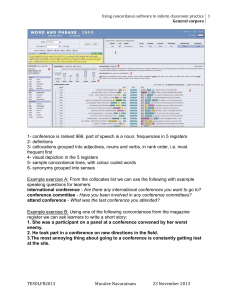

Introduction to Corpus Linguistics 1. What is a corpus? Latin corpus, “body”, plural corpora A body of text - a collection of texts – a large database of texts/linguistic examples Characteristics of a corpus according to McEnery and Wilson (2001) Machine-readable form – saved on and analysed by a computer Usually very large – but of a finite size Representative sample – Corpora are so big so that they can be a “representative sample” of a language o large enough to establish norms about the form of language being studied o large enough to reveal lots of cases of rare or unusual uses of language that we might not get from a smaller sample. o standard reference or ‘benchmark’ Often annotated – extra linguistic information added to the raw data o Annotation also known as TAGGING o e.g. the grammatical class of each word in a text (noun, verb, etc) A corpus could be described as “a finite-sized body of machine-readable text, sampled in order to be maximally representative of the language variety under consideration.” (p.32) 2. Corpus Linguistics Characteristics of corpus linguistics according to Biber, Conrad & Reppen (1998:4) Uses a corpus Uses computers for analysis Empirical – analysing actual patterns of language use Depends on quantitative and qualitative analytical techniques Corpus linguistics is the study of language using corpora The basic idea: by analysing VERY large amounts of textual data, we can find out things about language that we can’t find out any other way Allows us to test theories about language Removes bias Helps us to spot common and rare language phenomena Corpora may contain different sorts of data… Written data – extracts from books, magazines, newspapers, websites… Spoken data – transcripts of meetings, lectures, radio programs, everyday conversations… Some corpora contain a mixture of both (so both sorts of language are represented) 1 3. Empiricism and the history of corpus linguistics Corpus linguistics is an empirical method – it based on real-world data However, at the time when the first very large corpora were being compiled, empirical methods were out of fashion in linguistics. This was due to the Chomskyan revolution in linguistics, in which methods based on introspection and intuition were much more important. Empirical approaches pay less attention to the internal mind of an individual native speaker, and recognise that people’s intuitions about their own language may not be accurate So the only way to see how language is used, is to look at examples of ordinary, everyday language (written or spoken) However, after a period of some years the tide turned and corpora began to be used more widely. Some important milestones include: 1960s The Brown corpus 1 million word sample of American English Compiled by Francis and Kucera, Brown University. Classed as “a waste of time” by some of their contemporaries http://icame.uib.no/brown/bcm.html 1970s The LOB corpus “Lancaster-Oslo/Bergen”. British English match for Brown Compiled by Geoffrey Leech at Lancaster and others http://clu.uni.no/icame/manuals/BROWN/INDEX.HTM 1980 The London-Lund corpus 500K words of spoken British English http://clu.uni.no/icame/manuals/LONDLUND/INDEX.HTM 1986 The Kolhapur Corpus (and other international corpora) 1 million words of Indian English http://clu.uni.no/icame/manuals/KOLHAPUR/INDEX.HTM 1980s 1996: The Helsinki Corpus Texts from 750CE to 1700CE Diachronic corpus (includes text across time). 1.5 million words. http://clu.uni.no/icame/manuals/HC/INDEX.HTM Later corpora have tended to get bigger and bigger: 1990s The British National corpus 100 million words of British English. (produced by a consortium including Lancaster) http://www.natcorp.ox.ac.uk/ The Bank of English 524 million words (and counting) http://www.titania.bham.ac.uk/ 2000s The English Gigaword 1756 million words, released 2003, consists mostly of newswire data http://www.ldc.upenn.edu/Catalog/CatalogEntry.jsp?catalogId=LDC2003T05 However, corpus linguistics also uses smaller, more specialised corpora, for example: Lancaster Newsbooks Corpus (Tony McEnery and Andrew Hardie). 800,000 words of text from newspapers published in the first half of 1654. Used to study the origins of English journalism http://www.lancs.ac.uk/fass/projects/newsbooks/ Note that the lists above are just a sample of a few of the very many corpora that have been collected in a huge range of languages and dialects. See URLs below for a few more examples: http://clu.uni.no/icame/manuals/ http://ucrel.lancs.ac.uk/corpora.html 2 4. The British National Corpus (BNC) Currently, one of the best contemporary UK English corpora 100 million words from the early 1990s represents a wide range of both spoken and written modern British English Written data o 90 million words o Includes extracts from newspapers, academic books, popular fiction, letters and university essays Spoken data o 10 million words o Includes demographic data and context governed data The demographic part · transcripts of about 900 everyday unscripted spoken conversations The context-governed part · spoken language collected in public contexts – e.g. radio phone-ins, government meetings, classroom interactions 5. Exploiting a corpus 5.1 Wordlists (also known as frequency lists) All of the words in a corpus presented in alphabetical order or sorted according to their frequency. Basic word counts: how often does each word occur in the corpus? frequency lists compiled by computer This can give us more useful information than you might suspect… … but the frequency statistics still needs interpreting 5.2 Concordances A computerised search for all the examples of a word or a phrase in a corpus. Concordance lines show the results of the search and include the search term plus some of the surrounding context for each example. Usually shown in a sort of table with the search term highlighted in some way This informs us about the ways in which a word is usually used in actual sentences 5.3 Collocation Collocation is the relationship between words that tend to occur together Words which occur more frequently in the vicinity of word X than they do elsewhere in the corpus are called the collocates of X. Based on frequency (how frequent separate vs. how frequent together) Some computer tools can discover non-obvious collocates using statistics. Collocation forms part of a word’s meaning o “You shall know a word by the company it keeps” (Firth 1957:11) o The company a word keeps: implicit associations or assumptions o Near-synonyms often differ in terms of their collocations… 3 5.4 Statistical significance Sometimes just looking at frequency in a text can be a bit useless… We are really interested in words or other linguistic features that are unusually prominent … that is, more frequent in the text than in the language as a whole These are often the features that have most importance for a text But how do we know what counts as “unusually prominent”? We can use mathematical procedures called significance tests We can work out whether a difference in the statistics is significant or not A test often used in humanities is called the Chi-square test, but in corpus linguistics we often use one called log-likelihood 5.5 Keywords A keyword is a word that is unusually frequent in a text or corpus Based on comparison with a benchmark or reference corpus The difference must be statistically significant Keywords are often important to the meaning or theme(s) of the text They can be a good guide to what would be interesting to investigate further 6. Corpus annotation Annotation = extra information added to the text ( also known as TAGGING) EG: the grammatical class of each word in a text (noun, verb, etc) (POS tagging – see below) 6.1 Part-of-speech (POS) tagging POS tagging is the most basic type of grammatical analysis of a corpus. An example tagset: the C7 tagset (devised at Lancaster). See: http://ucrel.lancs.ac.uk/claws7tags.html For example – verbs o V = all verbs o VV, VB, VH, VD = lexical and auxiliary verbs o VV0 = root form “go”, “see” o VVZ = -es form “goes”, “sees” o VVG = -ing form “going”, “seeing” o VVD = past tense “went”, “saw” Tags are useful for improved corpus searches For instance, can o can as Verb – ‘He can do it’ o can as Noun – ‘That’s opened a can of worms!’ So, we can use tags to narrow the search Tagging is usually done not by hand but by a specialised computer program. An example POS tagger program: the CLAWS system (developed at Lancaster). See: http://ucrel.lancs.ac.uk/claws/trial.html 4 6.2 How do taggers work? Some words are looked up in a computerised dictionary or lexicon o Other words can have multiple tags: e.g. “dogs” – plural noun (NN2) or third person singular verb (VVZ)? o Words like this are worked out based on the surrounding tags by 1 of 2 methods: Rule-based – the computer is given rules about what tags can and can’t possibly follow one another and uses these to work out the correct tag Probabilistic (or stochastic) – the computer uses information about how frequently tags follow one another to work out what the tag is likely to be Tagger programs make mistakes: they are not 100% accurate (CLAWS 96-97% accurate) Note that, particularly in probabilistic tagging, the computer extracts information from a corpus and uses that information to help it understand / analyse / process other examples of language. 6.3 Semantic tagging Computers can, to some extent, understand the meaning of words in the same way they understand grammar Each word is given a label to say what type of meaning that word has As with POS tagging, semantic tags can be added to text by a computer program At Lancaster we use 21 basic semantic categories. See: http://ucrel.lancs.ac.uk/usas/ These have more detailed subcategories. See http://ucrel.lancs.ac.uk/usas/semtags.txt 6.4 Why annotate? Training the computer to process language better Helping searches in corpora Allowing us to search for / count up patterns of grammar or meaning, rather than just the words There can be an “upward spiral” effect: a machine-tagged corpus can be checked, improved, then fed back in again to produce an even better tagging program! 7. Applications of Corpora and Corpus Linguistics 7.1 Corpora in lexicography Early lexicography: the lexicographer’s brain – Samuel Johnson’s dictionary Later lexicography: readers’ observations – The Oxford English Dictionary (1st ed.) Modern lexicography is based largely on corpora 7.2 Other applications The study of grammar Variation studies Historical studies Comparing different languages Stylistics research And there are “real-world” applications EG: machine translation requires both Dictionary lookup (corpus-based lexicon) and Grammar analysis for good translation 5 8. Conclusion Corpus linguistics is an empirical methodology It relies on scanning large computerised bodies of text Corpus methods were frowned upon during the “Chomskyan revolution” in the 1960s… … but in the 70s, 80s and 90s they have come into their own There are different ways to get information from a corpus: frequency lists, concordances, etc. Corpora can be used in, for example, lexicography, the study of grammar, etc. Computers can be programmed to process language to some degree – often by absorbing linguistic knowledge from annotated corpora The computer can’t do it all for us – we still have to analyse the results and ask “but what does all this mean??” References Biber, D. Conrad, S. & Reppen, R. (1998) Corpus Linguistics: Investigating Language Structure and Use. Cambridge University Press. Firth, J.R. (1957) A synopsis of linguistic theory, 1930–1955. Studies in Linguistic Analysis (pp. 1–32). Special Volume, Philological Society. McEnery, T. & Wilson, A. (2001) Corpus Linguistics (2nd Ed.). Edinburgh University Press. Further Reading Aijmer, K. (1991) English Corpus Linguistics. London: Longman. Archer, D (2007) Computer-assisted literary stylistics: the state of the field. In Lambrou, M and Stockwell, P (eds.) Contemporary Stylistics. London: Continuum. Pages 244-256. Baker, P, Hardie A and McEnery, A (2006) A glossary of Corpus Linguistics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. Hunston, S (2002) Corpora in applied linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Kennedy, G. (1998) An Introduction to Corpus Linguistics. London: Longman. Mahlberg, M. (2007) ‘A corpus stylistic perspective on Dickens's Great Expectactions’. In M. Lambrou and P. Stockwell (eds) Contemporary Stylistics. Routledge, pp. 19-31. McEnery, A., Z. Xiao & Y. Tono (2005) Corpus-based language studies : An advanced resource book . London : Routledge. Meyer, C. (2002) English Corpus Linguistics. Cambridge University Press. Semino, E and Short, M (2004) Corpus stylistics : speech, writing and thought presentation in a corpus of English writing. London: Routledge. Tribble, C. (2000) Genres, keywords, teaching: towards a pedagogic account of the language of project proposals. In Burnard, L. and McEnery, T. (eds) Rethinking language pedagogy from a corpus perspective. Berlin: Peter Lang, pp 74-90 Some Internet Resources Short course on corpus linguistics on the Lancaster University website The research centre for Lancaster University BNC Frequencies BNC query tool Log Likelihood information/calculator http://www.lancs.ac.uk/fss/courses/ling/corpus/ http://ucrel.lancs.ac.uk/ http://ucrel.lancs.ac.uk/bncfreq/ http://corpus.byu.edu/bnc http://ucrel.lancs.ac.uk/llwizard.html 6