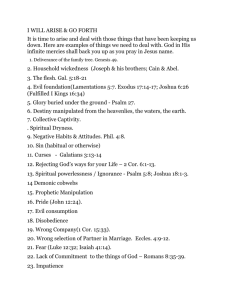

Table of Contents

advertisement