Hegenscheid et al. Potentially relevant incidental findings on

advertisement

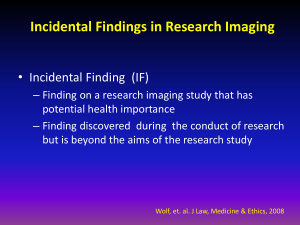

Hegenscheid et al. Potentially relevant incidental findings on research whole-body MRI in the general adult population: frequencies and management. EurRadiol 2012 SUPPLEMENTARY WEB APPENDIX This appendix consists of online material only and includes an own reference list that is independent from the journals’ article reference list. This appendix was provided by the authors to give readers additional information on the decisions made by the advisory board for the follow-up of incidental findings. HEAD BRAIN TUMOUR Heterogeneous group of intra-axial and extra-axial tumours with benign or malignant aspect. Management of incidental findings has been widely discussed for study MRI of the head [1, 2]. Disclosed benign tumours were intraventricular tumours, large arachnoid cysts, large meningiomas, and a vestibular schwannoma. All of these benign tumours were disclosed due to perifocal oedema indicating space-occupying growth or location in a region with high functional priority (e.g., brain stem, eloquent brain region). Disclosed malignant tumours were suspicious for glioma or metastasis. One participant presented with an extracranial soft tissue tumour with invasive intracranial growth. All were disclosed due to their life-threatening nature [3, 4]. PITUITARY MICRO-/ MACROADENOMA Pituitary microadenoma: intrasellar lesion with a maximum diameter < 10 mm. Pituitary macroadenoma: sellar-suprasellar mass without separately identifiable pituitary gland. Pituitary cyst: intrasellar or sellar-suprasellar cystic lesion. All lesions suspicious for microadenoma were communicated due to a possible hormone-producing state. Macroadenomas were disclosed due to possible involvement of the optic chiasm and cavernous sinus, and affected study subjects were recommended to undergo assessment of clinical symptoms as well as ophthalmological/endocrinological evaluation [5]. ACUTE BRAIN INFARCTION Acute cerebral infarction was diagnosed by diffusion-weighted imaging. Infarctions encountered were silent cerebral infarctions (neurologically asymptomatic). Silent cerebral infarction was found to more than double the risk of subsequent stroke in both population- and hospital-based cohort studies, regardless of the presence of cardiovascular risk factors [6-9]. This finding was communicated to allow subjects with twice the normal risk of major stroke to undergo neurological check-up 1 Hegenscheid et al. Potentially relevant incidental findings on research whole-body MRI in the general adult population: frequencies and management. EurRadiol 2012 for identification of potentially treatable risk factors. SUBDURAL HAEMATOMA Crescentic, extra-axial convexity collection, crossing sutures but not dural attachments. One subdural haematoma was disclosed due to its space-occupying size. NORMAL PRESSURE HYDROCEPHALUS (NPH) NPH was suspected according to the evidence-based guidelines for the diagnosis of NPH [10]. Diagnosis of NPH required correlation with clinical symptoms. Suspected NPH was disclosed to allow neurological work-up since timely diagnosis and treatment by ventricular shunting can reverse symptoms, while natural history of NPH leads to chronic impairment [11]. NECK CYSTIC OR SOLID PHARYNGEAL OR LARYNGEAL TUMOUR Handling of cystic or solid oropharyngeal and laryngeal masses was difficult because their diagnosis relied on only two unenhanced MR sequences of the neck. The advisory board decided each case of asymmetry by interdisciplinary consensus. Almost all asymmetries, excepting simple cysts, were disclosed since the incidence and mortality of oropharyngeal and laryngeal cancer is highest in the state in which the SHIP study was conducted compared to the other German states [12]. The relatively low risk of complications associated with panendoscopy of the nasopharyngeal and laryngeal cavities recommended for follow-up justified higher follow-up rates. CYSTIC OR SOLID SALIVARY GLAND TUMOUR Handling of cystic or solid salivary gland masses was difficult because their diagnosis relied on only two unenhanced MR sequences of the neck. The advisory board decided by interdisciplinary consensus which masses should be followed up by assessment of clinical signs and symptoms and ultrasonography. GOITRE WITH TRACHEAL COMPRESSION Diffuse, multinodular enlargement of the thyroid gland with tracheal compression. Goitres were disclosed in case of tracheal compression since significant airway compression indicates need for surgical treatment [13]. THYROID TUMOUR 2 Hegenscheid et al. Potentially relevant incidental findings on research whole-body MRI in the general adult population: frequencies and management. EurRadiol 2012 Thyroid mass suspicious of malignancy: irregular demarcation from surrounding structures, invasion, metastatic cervical lymphadenopathy. Management of incidental thyroid masses on MRI/CT has been discussed controversially [14]. Assessment required risk stratification by history, physical examination, and ancillary tests (serum TSH, ultrasonography) [13, 15]. Since the SHIP study provided thyroid ultrasonography and serum TSH values for each participant in the internal branch of the study, the advisory board only disclosed masses with high propability of malignancy, whereas all nondisclosed nodules were automatically evaluated in the normal course of the SHIP study protocol. CHEST LUNG NODULE Lung lesion completely surrounded by lung parenchyma < 3 cm in diameter [16]. Pulmonary nodules were reported according to the guidelines of the Fleischner Society [17, 18]. Subjects with nodules > 4 mm were recommended to undergo initial CT. If CT confirmed the nodule seen on MRI, further follow-up was recommended following the guidelines of the Fleischner Society. PNEUMONIA Segmental/lobar consolidation of the lung due to inflammatory infiltration in asymptomatic/ oligosymptomatic participants (silent infection) [19]. Asymptomatic/oligosymptomatic pneumonia was disclosed since, especially in the elderly, pneumonia can present as silent infection with atypical features (deteriorating general condition, confusion, and lethargy) but is nevertheless a major cause of morbidity and mortality [20]. Poststenotic pneumonias in central lung carcinomas are mostly subclinical infections [21]. Consequently, an underlying carcinoma should be ruled out. PLEURAL EFFUSION Fluid accumulation in the pleural space replacing the pulmonary volume. Pleural effusion was disclosed if effusion was so largeof such a volume that respiratory restriction seemed likely, indicated by pulmonary dystelectasis or atelectasis. LIVER LIVER LESION A benign lesion (cyst, haemangioma, adenoma, focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH)) or 3 Hegenscheid et al. Potentially relevant incidental findings on research whole-body MRI in the general adult population: frequencies and management. EurRadiol 2012 malignant lesion (hepatocellular carcinoma) was assumed when the respective imaging criteria were present. Lesions were classified as unclear if morphology on plain imaging was not definitively benign and criteria for malignancy (destructive or invasive growth) were not fulfilled. (1) FNHs have few complications, and there is no evidence of malignant transformation [22]. Disclosure of FNH was based on their responsiveness to oestrogens with larger, more vascular tumours occurring in women on oral contraceptives. Therefore, FNH was communicated in premenopausal women to allow affected women and their gynaecologists to discuss discontinuation of oral contraceptives [23]. (2) Large cysts were disclosed on the basis of their higher rate of complications such as spontaneous haemorrhage, rupture, infection, or mechanical compression of adjacent structures to allow correlation with clinical symptoms [24]. (3) Most hepatic haemangioma remain stable over time and require no treatment. Treatment or follow-up is not indicated for lesions <5 cm in diameter, whereas lesions >15 cm in diameter may need resection and were therefore disclosed [25]. (4) All adenomas were communicated because of an approx. 10% risk of malignant transformation to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [26]. (5) Unclear liver lesions need further imaging evaluation (MRI with liver-specific contrast medium/ ultrasonography) for reliable characterization. (6) Liver lesions highly suspicious for hepatocellular carcinoma or metastasis were communicated due to their malignant nature. CIRRHOSIS OR HEMOCHROMATOSIS Cirrhosis: chronic liver disease characterized by diffuse parenchymal injury, fatty and fibrotic tissue changes, and formation of abnormal nodules. Haemochromatosis: iron overload disorder with structural and functional impairment of involved organs. Decreased signal intensity of the liver on T1- and T2-weighted images. Haemochromatosis and cirrhosis are severe pathologies shortening life expectancy and lowering quality of life [27, 28]. These conditions were disclosed to allow evaluation of etiology and risk factors as well as to facilitate possible treatment. BILIARY SYSTEM CHOLESTASIS 4 Hegenscheid et al. Potentially relevant incidental findings on research whole-body MRI in the general adult population: frequencies and management. EurRadiol 2012 Dilatation of the choledochal duct > 7mm/10mm or of intrahepatic bile ducts > 3mm in participants without/after cholecystectomy, respectively. Natural history of chronic cholestasis leads to secondary biliary cirrhosis of the liver. Patients with this condition require evaluation of etiology and management of treatable causes. Recommendations included assessment of paraclinical and clinical signs as well as ultrasonographic correlation. CHRONIC CHOLECYSTITIS Chronic cholecystitis: diffuse gall bladder wall thickening and presence of gallstones. Chronic cholecystitis was often seen and was only disclosed in case of acute exacerbation: pericholecystic fluid and adjacent fat signal intensity changes [29]. PANCREAS CHRONIC PANCREATITIS Chronic pancreatitis: pancreatic atrophy, pancreatic duct dilatation and side branch dilatation, irregularity of the pancreatic ducts, calcifications, pseudocysts, and biliary obstruction. Chronic pancreatitis was disclosed due to a natural history with exocrine/endocrine insufficiency and chronic pain syndrome to allow evaluation and enable management of treatable causes [30]. Recommendations included assessment of paraclinical and clinical signs as well as ultrasonographic correlation. PANCREATIC TUMOUR Unclear pancreatic lesions disclosed were suspicious for malignancy but could also be tumour-simulating benign lesions such as inflammatory pseudotumours or complex pseudocysts. Since unenhanced imaging with a single modality does not differentiate cancer and focal pancreatitis, disclosure allowed correlation with additional imaging findings (contrast-enhanced CT and ERCP with biopsy) [31, 32]. The follow-up regimen was based on the White Paper of the ACR incidental findings committee [33]. SPLEEN & LYMPHATIC SYSTEM SPLENOMEGALY Splenomegaly: craniocaudal length of the spleen exceeding 12 cm. Splenomegaly was disclosed if suggestive of systemic diseases of the lymphatic system (e.g., generalized lymphadenopathy with concomitant splenomegaly), metastasis (e.g., abdominal lymphadenopathy in conjunction with suspicious 5 Hegenscheid et al. Potentially relevant incidental findings on research whole-body MRI in the general adult population: frequencies and management. EurRadiol 2012 intestinal, hepatic, or pancreatic mass), or reactive lymphadenopathy with concomitant inflammation suggested by severe tissue oedema. All of these cases were presented to the advisory board with disclosure being decided on a case-bycase basis. SPLENIC TUMOUR Splenic lesions were classified as lesions with a distinct MRI appearance (cyst/hemangioma, calcification, infarction) and unclear lesions. Unclear lesions could not be reliably characterized on the basis of the available plain MR sequences. Correlation with other imaging modalities was suggested to rule out inflammatory and infectious disease, hematologic disorders, and solid malignancies [34]. INTESTINE GASTROINTESTINAL TUMOR Solid soft tissue mass of the intestinal wall, which reproduced in at least two different sequences to exclude peristalsis as cause of intestinal wall thickening. Available MR images were limited, not least because no contrast agent was used. Cases in question were presented to the advisory board with disclosure being decided on a case-by-case basis. LARGE HERNIATION Opening or weakness in the muscular structure of the abdominal wall with protrusion of an organ or part of an organ out of the abdominal cavity. Large herniations with protrusion of organs were disclosed due the risk of incarceration [35]. KIDNEY RENAL CYST OR TUMOUR We adopted the Bosniak classification system to grade cystic renal lesions [36,37]. The differential diagnosis of renal masses includes angiomyolipoma and renal cell carcinoma. Category I cysts were disclosed > 8 cm in diameter due to the increased risk of hemorrhage especially in individuals undergoing anticoagulation therapy [38, 39]. Simple category II cysts are benign, but cyst category IIF (a cystic lesion with multiple thin septa, or septa thicker than hairline, or a thick calcification) are not invariably benign [40, 41]. Disclosure was implemented for cysts category ≥ IIF with follow-up 6 Hegenscheid et al. Potentially relevant incidental findings on research whole-body MRI in the general adult population: frequencies and management. EurRadiol 2012 according to the recommendations of the White Paper of the ACR incidental findings committee [33]. Although benign, renal angiomyolipomas were always disclosed since angiomyolipoma was found to be the most frequent misdiagnosis for renal cell carcinoma [42]. Renal angiomyolipomas were also disclosed because they are associated with an increased risk of tumoural haemorrhage when their size exceeds 4 cm [43]. Kidney masses with an invasive and/or destructive growth pattern are highly suspicious for renal cell carcinoma and were disclosed due to their probably malignant nature. ADRENAL TUMOUR Adrenal lesion ≥ 1 cm. All adrenal masses ≥ 1 cm were disclosed. Follow-up was recommended according to the White Paper of the ACR incidental findings committee to allow correlation with prior imaging and/or follow-up by MRI or CT [33]. CHRONIC URINARY OBSTRUCTION We differentiated chronic urinary retention with dilatation of the calicopelvic system with concomitant atrophy of renal parenchyma from acute urinary retention with dilatation of the calicopelvic system and normal renal parenchyma. Chronic and acute urinary retention was always disclosed since both will lead to chronic kidney disease if untreated and persisting [44, 45]. URINARY BLADDER MASS Localized circumscribed urinary bladder masses were differentiated from global thickening of the urinary bladder wall. The first is suspicious for urinary bladder malignancy, the second is a sign of chronic bladder damage. Since the acquired MR sequences are limited regarding evaluation of the urinary bladder, among others because evaluation depends on bladder filling at the time of imaging, circumscribed or diffuse wall thickening was always disclosed to enable further diagnostic work-up (ultrasonography, cystoscopy) and correlation with possible clinical symptoms. MALE GENITAL SYSTEM PROSTATIC HYPERPLASIA OR TUMOUR Probably benign enlargement of the prostate due to nodular hyperplasia causing progressive urinary obstruction was distinguished from enlargement of the prostate (asymmetric enlargement, probably malignant invasive growth, 7 Hegenscheid et al. Potentially relevant incidental findings on research whole-body MRI in the general adult population: frequencies and management. EurRadiol 2012 lymphadenopathy) suggestive of prostatic cancer. Volumetry of the prostate was performed in all men ([transverse diameter in cm]3 x /6) [46]. Prostatic enlargement 60 ml was disclosed to allow urological risk stratification for urinary obstruction and prostate cancer (transabdominal/ transurethral ultrasound and biopsy, correlation with clinical symptoms and paraclinical parameters) [47]. INGUINAL TESTIS Incomplete testicular descent into the scrotum with testis in the inguinal canal. An inguinal testis has an increased risk of malignant transformation and infertility and was disclosed depending on the participant’s age [48-50]. TESTICULAR AND EPIDIDYMAL MASS Cystic or solid testicular or epididymal mass with benign or malignant aspect. Simple scrotal cysts (epididymal/ testicular/ tunica albuginea cyst, spermatocele] are benign and were not disclosed. Solid scrotal masses were generously disclosed with recommendation for urological clarification. For scrotal masses there are multiple differential diagnoses, and differentiation requires correlation with clinical signs and symptoms, paraclinical parameters and alternate imaging modalities, espescially ultrasonography, and ultimativley inguinal exploration [51-53]. SEMINAL VESICLE MASS Generalized enlargement of the seminal vesicles was distinguished from focal lesions. Diffuse enlargement was not disclosed since underlying conditions are benign (inflammation, radiotherapy-induced changes, amyloidosis). Focal lesions suggesting tumor invasion (cancer of the prostate, bladder or rectum) were disclosed [54]. FEMALE GENITAL SYSTEM UTERINE OR CERVICAL TUMOUR Benign masses of the uterus and cervix (leiomyoma, adenomyoma/ adenomyosis, endometrial hyperplasia, polyp, Nabothian cysts) and probably malignant masses (endometrial or cervical carcinoma, endometrial sarcoma) were differentiated. None of the definitely benign uterine lesions listed above were disclosed. For unclear uterine and cervical masses, the interdisciplinary advisory board decided on a caseby-case basis which masses to follow up. The relatively low risk of complications of colposcopy and ultrasonography recommended for follow-up justified higher follow- 8 Hegenscheid et al. Potentially relevant incidental findings on research whole-body MRI in the general adult population: frequencies and management. EurRadiol 2012 up rates [55, 56]. COMPLEX OVARIAN CYST OR TUMOUR Ovarian masses were differentiated into benign (functional cysts, haemorrhagic cysts), unclear, and probably malignant (solid tumours or mixed solid and cystic tumours, size > 8 cm, local invasion, peritoneal fluid, and adenopathy). In premenopausal women, complex cysts with suspected haemorrhage and cystic tumours were disclosed, while simple cystic lesions (functional cysts) were not. In postmenopausal women, cysts were disclosed if diameter exceeded 2 cm due to the increased risk of ovarian cancer to allow correlation with ultrasound and paraclinical parameters (Ca-125) [57, 58]. All unclear ovarian masses and those with signs of malignancy (solid tumour or mixed solid and cystic tumour, size > 8 cm, local invasion, peritoneal fluid, adenopathy) were disclosed [59-61]. BREAST LESION (≥ BI-RADS 3) Breast lesions in women who underwent the contrast-enhanced MR mammography module were classified according to the Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS). Breast lesions classified BI-RADS 3 were disclosed. For category 3 lesions, close follow-up was recommended [62, 63] as well as ultrasonographic correlation [64]. For category 4 or 5 lesions, biopsy was recommended. SPINE AND MUSCULOSKELETAL SYSTEM ABSOLUTE SPINAL CANAL STENOSIS WITH MYELOPATHY Acquired stenosis of the cervical/lumbar spinal canal secondary to degenerative changes with intramedullary T2-hyperintensity representing myelomalacia, demyelination, or oedema. Natural history of cervical/lumbar spinal canal stenosis is progressive and dynamic with mainly irreversible damage to the spinal cord/cauda equina. Disclosure allowed diagnostic and therapeutic interruption of the progressive disabling process [65, 66]. INTRASPINAL TUMOUR Intraspinal lesions were classified into intramedullary lesions, intradural extramedullary lesions, and extradural lesions. There are many differential diagnoses depending on many features including lesion site, signal intensities, and clinical and paraclinical parameters [67, 68]. 9 Hegenscheid et al. Potentially relevant incidental findings on research whole-body MRI in the general adult population: frequencies and management. EurRadiol 2012 Without contrast-enhanced MR images, differentiation of benign and malignant lesions was not possible. Therefore all intraspinal lesions were disclosed to allow further diagnostic steps. BONE LESION Bone lesions encountered were bone cysts, chondrogenic bone tumors (with benign aspect], and unclear bone lesions not classifiable on the basis of plain MR images. Bone cysts were disclosed if size and location suggested risk of fracture (e.g., femoral neck, case-by-case decision by the advisory board]. Most chondrogenic bone tumours were assumed to be enchondromas, which are primary benign tumours with little potential of malignant transformation. The risk of secondary malignant transformation is increased for endochondromas located in the axial skeleton and > 5 cm in diameter [69]. Enchondroma cannot reliably be differentiated from low-grade chondrosarcoma by MRI alone [70, 71]. Chondrogenic bone tumours were disclosed if located in the axial skeleton and diameter > 5cm for short-time follow-up and correlation with clinical signs and other imaging modalities. SEVERE BONE EDEMA Differential diagnoses for bone marrow oedema vary widely depending on localization, age, clinical symptoms, and radiographic appearance (osteoarthritis, osteonecrosis, traumatic bone bruise, bone infarction, insufficiency/stress fracture, metastasis, transient bone marrow oedema syndrome, septic joint, osteomyelitis, leukaemia, and lymphoma) [72]. Bone oedema was not disclosed if it was most likely due to osteoarthritis, traumatic bone bruise, bone infarction, or early osteonecrosis. Bone oedema was communicated when it was assumed to be associated with fracture, osteomyelitis, osteonecrosis with destruction of the joint surface, and possible malignancy. HEART AND VESSELS HEART FAILURE Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was obtained for participants who underwent the cardiac MR module. If LVEF was < 35% heart failure was diagnosed. Community-dwelling elderly persons with impaired LVEF have a substantial risk of death from congestive heart failure [73]. Therefore LVEF < 35% was disclosed. MYOCARDIAL TUMOUR One participant presented with a cardiac mass most likely originating from the 10 Hegenscheid et al. Potentially relevant incidental findings on research whole-body MRI in the general adult population: frequencies and management. EurRadiol 2012 myocardium. The advisory board agreed upon disclosure since cardiac tumours are rare entities requiring special expertise and further diagnostic steps. PERICARDIAL EFFUSION One participant presented with pericardial effusion impairing diastolic ventricular filling. The advisory board agreed upon disclosure since further increase in intrapericardial fluid volume was expected to cause decompensation. VASCULAR STENOSIS Arterial stenosis of the (1) renal artery and (2) aortic isthmus was identified. (1) Renal artery stenosis causes hypertension and progressive renal failure. The need for revascularization and its benefits have been discussed controversly [74,75]. Disclosure allowed individual assessment of the need for treatment. (2) One participant presented with aortic coarctation. The advisory board agreed upon disclosure due to the severely reduced life expectancy in untreated aortic coarctation [76]. VASCULAR ANEURYSM Arterial aneurysms of the (1) splenic artery, (2) renal artery, (3) abdominal aorta (AAA), and (4) thoracic aorta were identified. (1) No consensus has been reached regarding intervention in asymptomatic patients with splenic artery aneurysm. The smallest aneurysm that ruptured over a 4-year observation period at the Mayo Clinic was 2 cm [77]. It has been recommended to treat asymptomatic aneurysms greater than 2 cm in patients with a reasonable operative risk and life expectancy greater than 2 years [77, 78]. Therefore all splenic aneurysms were disclosed. (2)While the majority of renal artery aneurysms are asymptomatic, they are associated with hypertension in up to 73% of cases. A diameter greater than 1.5 cm requires repair. Aneurysm repair cures hypertension in 20-50% of cases [79]. Therefore, the single case encountered was disclosed. (3)An AAA is a focal dilation of the abdominal aorta ≥ 1.5 times its normal diameter, by convention infrarenal aorta ≥ 3 cm [80]. The risk of rupture correlates with diameter of the aneurysm: 5-5.9 cm: 11% per year and ≥ 6 cm: 25% per year [81]. All AAAs were disclosed with recommendations: 3-4 cm: yearly ultrasound 11 Hegenscheid et al. Potentially relevant incidental findings on research whole-body MRI in the general adult population: frequencies and management. EurRadiol 2012 examination, 4-4.5 cm: ultrasound examination every 6 months, ≥ 4.5 cm: referral to a vascular specialist [82]. (4)An aneurysm of the thoracic aorta is considered if diameter exceeds > 4.5 cm. All aneurysms need follow-up with regular imaging to monitor growth [83]. With regard to aneurysm size and risk of rupture or dissection, an annual rate of 2% for aneurysms < 5 cm, 3% for aneurysms 5 to 5.9 cm, and 7% for aneurysms > 6 cm was found [84]. Surgery is indicated for a diameter of > 5.5 cm or 6 cm in patients with an increased operative risk [83]. INTRACRANIAL ANEURYSM Intracranial aneurysm: saccular or fusiform dilatation of an intracranial artery. Whether incidental aneurysms should be treated preventively has been discussed controversially [85-87]. All findings were disclosed after neurosurgical/neuroradiological assessment by the advisory board with individualized recommendations for diagnosis, follow-up, and treatment. CAVERNOUS MALFORMATION Cavernous malformations (CMs) are benign vascular hamartomas with intralesional haemorrhages of different ages. CMs can cause seizures or intracranial haemorrhage, yet 40% of cases are asymptomatic. Asymptomatic persons need not be treated. Therefore all CMs were discussed in the advisory board. Disclosure was decided on a case-by-case basis taking into account age, localization, and size of the malformation (region with high functional priority, e.g., brain stem, eloquent brain regions). INTERNAL CAROTID ARTERY STENOSIS Internal carotid artery (ICA) stenosis was classified according to the NASCET method: % stenosis = (normal lumen - minimal residual lumen) / (normal lumen x 100) [88]. ICA stenosis 50% was disclosed to allow further individual assessment since in asymptomatic patients younger than 75 with carotid diameter reduction ≥ 70% carotid, endarterectomy was shown to halve the 5-year stroke risk [89]. Note–. Gray-shaded cells indicate precedents. 12 Hegenscheid et al. Potentially relevant incidental findings on research whole-body MRI in the general adult population: frequencies and management. EurRadiol 2012 REFERENCES 1. Illes J, Kirschen MP, Karetsky K et al (2004 Discovery and disclosure of incidental findings in neuroimaging research. J Magn Reson Imaging 20:743-747 2. Illes J, Rosen AC, Huang L et al (2004) Ethical consideration of incidental findings on adult brain MRI in research. Neurology 62:888-890 3. Katzman GL, Dagher AP, Patronas NJ (1999) Incidental findings on brain magnetic resonance imaging from 1000 asymptomatic volunteers. JAMA 282(1):36-9 4. Kim BS, Illes J, Kaplan RT, Reiss A, Atlas SW (2002) Incidental findings on pediatric MR images of the brain. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 23:1674-1677 5. Sonksen P, Sonksen C. (2008) Pituitary incidentaloma. Clinical Endocrinology 69:180 6. Bernick C, Kuller L, Dulberg C, et al (2001) Silent MRI infarcts and the risk of future stroke: the cardiovascular health study. Neurology 57:1222-1229 7. Bokura H, Kobayashi S, Yamaguchi S et al (2006) Silent brain infarction and subcortical white matter lesions increase the risk of stroke and mortality: a prospective cohort study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 15:57-63 8. Kobayashi S, Okada K, Koide H, Bokura H, Yamaguchi S (1997) Subcortical silent brain infarction as a risk factor for clinical stroke. Stroke 28:1932-1939. 9. Vermeer SE, Den Heijer T, Koudstaal PJ, Oudkerk M, Hofman A, Breteler MM (2003) Incidence and risk factors of silent brain infarcts in the population-based Rotterdam Scan Study. Stroke 34:392-396 10. Relkin N, Marmarou A, Klinge P, Bergsneider M, Black PM (2005) Diagnosing idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus. Neurosurgery 57:4-16 11. Shprecher D, Schwalb J, Kurlan R (2008) Normal pressure hydrocephalus: diagnosis and treatment. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 8:371-376 12. Katalinic A. (2010) GEKID-Atlas: Inzidenz und Mortalität von Krebserkrankungen in den Bundesländern. www.ekr.med.uni-erlangen.de/GEKID; Available via www.ekr.med.uni-erlangen.de/GEKID 13. Lansford CD, Teknos TN (2006) Evaluation of the thyroid nodule. Cancer Control 13:89-98 14. Yousem DM, Huang T, Loevner LA, Langlotz CP (1997) Clinical and economic impact of incidental thyroid lesions found with CT and MR. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 18:1423-1428 13 Hegenscheid et al. Potentially relevant incidental findings on research whole-body MRI in the general adult population: frequencies and management. EurRadiol 2012 15. Weber AL, Randolph G, Aksoy FG (2000) The thyroid and parathyroid glands. CT and MR imaging and correlation with pathology and clinical findings. Radiol Clin North Am 38:1105-1129 16. Austin JH, Muller NL, Friedman PJ et al (1996) Glossary of terms for CT of the lungs: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee of the Fleischner Society. Radiology 200:327-331 17. MacMahon H, Austin JH, Gamsu G, et al (2005) Guidelines for management of small pulmonary nodules detected on CT scans: a statement from the Fleischner Society. Radiology 237:395-400 18. MacMahon H (2010) Compliance with Fleischner Society guidelines for management of lung nodules: lessons and opportunities. Radiology 255:14-15 19. Hansell DM, Bankier AA, MacMahon H, McLoud TC, Müller NL, Remy J (2008) Fleischner Society: Glossary of Terms for Thoracic Imaging. Radiology 246:697-722 20. Feldman C (2001) Pneumonia in the elderly. Med Clin North Am 85:1441-1459 21. Casey KR (1995) Neoplastic mimics of pneumonia. Semin Respir Infect 10:131-142 22. Nguyen BN, Flejou JF, Terris B, Belghiti J, Degott C (1999) Focal nodular hyperplasia of the liver: a comprehensive pathologic study of 305 lesions and recognition of new histologic forms. Am J Surg Pathol 23:1441-1454 23. Nime F, Pickren JW, Vana J, Aronoff BL, Baker HW, Murphy GP (1979) The histology of liver tumors in oral contraceptive users observed during a national survey by the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer. Cancer 44:1481-1489 24. Benhamou JP (1994) Non-parasitic cystic diseases of the liver and intrahepatic biliary tree. In: Blumgart LH (1994) Surgery of the Liver and Biliary Tract, 2nd edn, Churchill Livingstone, New York 25. Farges O, Daradkeh S, Bismuth H. (1995) Cavernous hemangiomas of the liver: are there any indications for resection? World J Surg 19:19-24 26. Foster JH, Berman MM (1994) The malignant transformation of liver cell adenomas. Arch Surg 129:712-717 27. Achord JL (1989) Cirrhosis of the liver: new concepts. Compr Ther 15:11-16 28. Powell LW, George DK, McDonnell SM, Kowdley KV (1998) Diagnosis of hemochromatosis. Ann Intern Med 129:925-931 14 Hegenscheid et al. Potentially relevant incidental findings on research whole-body MRI in the general adult population: frequencies and management. EurRadiol 2012 29. Altun E, Semelka RC, Elias J et al (2007) Acute cholecystitis: MR findings and differentiation from chronic cholecystitis. Radiology 244:174-183 30. Ammann RW (2006) Diagnosis and management of chronic pancreatitis: current knowledge. Swiss Med Wkly 136:166-174 31. Schima W (2006) MRI of the pancreas: tumours and tumour-simulating processes. Cancer Imaging 6:199-203 32. Vanbeckevoort D (2007) Solid pancreatic masses: benign or malignant. JBR- BTR 90:487-489 33. Berland LL, Silverman SG, Gore RM et al (2010) Managing incidental findings on abdominal CT: white paper of the ACR incidental findings committee. J Am Coll Radiol 7:754-773 34. Elsayes KM, Narra VR, Mukundan G, Lewis JS, Jr., Menias CO, Heiken JP (2005) MR imaging of the spleen: spectrum of abnormalities. Radiographics 25:967982 35. Aguirre DA, Santosa AC, Casola G, Sirlin CB (2005) Abdominal wall hernias: imaging features, complications, and diagnostic pitfalls at multi-detector row CT. Radiographics 25:1501-1520 36. Bosniak MA (1986) The current radiological approach to renal cysts. Radiology 158:1-10 37. Bosniak MA (1991) Difficulties in classifying cystic lesions of the kidney. Urol Radiol 13:91-93 38. Capitanini A, Tavolaro A, Rosellini M, Rossi A (2009) Wunderlich syndrome during antiplatelet drug therapy. Clin Nephrol 71:342-344 39. Spires SM, Gaede JT, Glenn JF (1980) Death from renal cyst. Urology 16:606- 607 40. Aronson S, Frazier HA, Baluch JD, Hartman DS, Christenson PJ (1991) Cystic renal masses: usefulness of the Bosniak classification. Urol Radiol 13:83-90 41. Bosniak MA (1994) How does one deal with a renal cyst that appears to be Bosniak class II on a CT scan but that has sonographic features suggestive of malignancy (e.g., nodularity of wall or a nodular, irregular septum)? AJR Am J Roentgenol 163:216 42. Silverman SG, Lee BY, Seltzer SE, Bloom DA, Corless CL, Adams DF (1994) Small (< or = 3 cm) renal masses: correlation of spiral CT features and pathologic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol 163:597-605 15 Hegenscheid et al. Potentially relevant incidental findings on research whole-body MRI in the general adult population: frequencies and management. EurRadiol 2012 43. Yamakado K, Tanaka N, Nakagawa T, Kobayashi S, Yanagawa M, Takeda K (2202) Renal angiomyolipoma: relationships between tumor size, aneurysm formation, and rupture. Radiology 25:78-82 44. de Zeeuw D, Hillege HL, de Jong PE (2005) The kidney, a cardiovascular risk marker, and a new target for therapy. Kidney Int Suppl 98:25-29 45. U.S. Renal Data System (2005) Annual data report: Atlas of end-stage renal disease in the United States. Bethesda, Available via http://www.usrds.org/atlas.htm. 46. Singer EA, Golijanin DJ, Davis RS, Dogra V (2006) What's new in urologic ultrasound? Urol Clin North Am 33:279-286 47. Roehrborn CG (2011) Male lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). Med Clin North Am 95:87-100 48. Ritzen EM (2008) Undescended testes: a consensus on management. Eur J Endocrinol 159:87-90 49. Ulbright T, Amin M, Young R (1999) Miscellaneous primary tumors of the testis, adnexa, and spermatic cord. Atlas of Tumor Pathology, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington, DC:235-366 50. Wood HM, Elder JS (2009) Cryptorchidism and testicular cancer: separating fact from fiction. J Urol 181:452-461 51. Hussain A, Hosking DH (2003) The unsuspected nonpalpable testicular mass detected by ultrasound: a management problem. Can J Urol 10:1764-1766 52. Powell TM, Tarter TH (2006) Management of nonpalpable incidental testicular masses. J Urol 176:96-98 53. Woodward PJ, Sohaey R, O'Donoghue MJ, Green DE (2002) From the archives of the AFIP: tumors and tumorlike lesions of the testis: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics 22:189-216 54. Kim B, Kawashima A, Ryu JA, Takahashi N, Hartman RP, King BF (2009) Imaging of the seminal vesicle and vas deferens. Radiographics 29:1105-1121 55. Kido A, Togashi K, Koyama T, Yamaoka T, Fujiwara T, Fujii S (2003) Diffusely enlarged uterus: evaluation with MR imaging. Radiographics 23:1423-1439 56. Okamoto Y, Tanaka YO, Nishida M, Tsunoda H, Yoshikawa H, Itai Y (2003) MR imaging of the uterine cervix: imaging-pathologic correlation. Radiographics 23:425-445 57. McDonald JM, Modesitt SC (2006) The incidental postmenopausal adnexal mass. Clin Obstet Gynecol 49:506-516 16 Hegenscheid et al. Potentially relevant incidental findings on research whole-body MRI in the general adult population: frequencies and management. EurRadiol 2012 58. Perez-Lopez FR, Chedraui P, Troyano-Luque JM (2010) Peri- and post- menopausal incidental adnexal masses and the risk of sporadic ovarian malignancy: new insights and clinical management. Gynecol Endocrinol 26:631-43 59. Jeong YY, Outwater EK, Kang HK (2000) Imaging evaluation of ovarian masses. Radiographics 20:1445-1470 60. Stany MP, Hamilton CA (2008) Benign disorders of the ovary. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 35:271-284 61. Stany MP, Maxwell GL, Rose GS (2010) Clinical decision making using ovarian cancer risk assessment. AJR Am J Roentgenol 194:337-342 62. Hauth E, Umutlu L, Kummel S, Kimmig R, Forsting M (2010) Follow-up of probably benign lesions (BI-RADS 3 category) in breast MR imaging. Breast J 16:297-304 63. Sadowski EA, Kelcz F (2005) Frequency of malignancy in lesions classified as probably benign after dynamic contrast-enhanced breast MRI examination. J Magn Reson Imaging 21:556-564 64. Carbognin G, Girardi V, Calciolari C et al (2010) Utility of second-look ultrasound in the management of incidental enhancing lesions detected by breast MR imaging. Radiol Med 115:1234-1245 65. Emery SE (2001) Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy: Diagnosis and Treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 9:376-388 66. Hilibrand A, Rand N (1999) Degenerative lumbar stenosis: diagnosis and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 7:239-249 67. Gebauer GP, Farjoodi P, Sciubba DM et al (2008) Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Spine Tumors: Classification, Differential Diagnosis, and Spectrum of Disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am 90:146-162 68. Khanna AJ, Shindle MK, Wasserman BA et al (2005) Use of magnetic resonance imaging in differentiating compartmental location of spinal tumors. Am J Orthop 34:472-476 69. Geirnaerdt MJ, Hermans J, Bloem JL et al (1997) Usefulness of radiography in differentiating enchondroma from central grade 1 chondrosarcoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol 169:1097-1104 70. Flemming DJ, Murphey MD (2000) Enchondroma and chondrosarcoma. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol 4:59-71 17 Hegenscheid et al. Potentially relevant incidental findings on research whole-body MRI in the general adult population: frequencies and management. EurRadiol 2012 71. Murphey MD, Flemming DJ, Boyea SR, Bojescul JA, Sweet DE, Temple HT (1998) Enchondroma versus chondrosarcoma in the appendicular skeleton: differentiating features. Radiographics 18:1213-1237 72. Starr AM, Wessely MA, Albastaki U, Pierre-Jerome C, Kettner NW (2008) Bone marrow edema: pathophysiology, differential diagnosis, and imaging. Acta Radiol 49:771-786 73. Gottdiener JS, McClelland RL, Marshall R et al (2002) Outcome of congestive heart failure in elderly persons: influence of left ventricular systolic function. The Cardiovascular Health Study. Ann Intern Med 137:631-639 74. Chrysochou C, Kalra PA (2010) Current Management of Atherosclerotic Renovascular Disease - What Have We Learned from ASTRAL? Nephron Clinical Practice 115:73-81 75. Plouin PF, Rossignol P, Bobrie G (2001) Atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis: to treat conservatively, to dilate, to stent, or to operate? J Am Soc Nephrol 12:21902196 76. Campbell M (1970) Natural history of coarctation of the aorta. British Heart Journal. 32:633-640 77. Abbas MA, Stone WM, Fowl RJ et al (2002) Splenic artery aneurysms: two decades experience at Mayo clinic. Ann Vasc Surg 16:442-449 78. Trastek VF, Pairolero PC, Joyce JW, Hollier LH, Bernatz PE (1982) Splenic artery aneurysms. Surgery 91:694-699 79. Henke PK, Cardneau JD, Welling TH et al (2001) Renal artery aneurysms: a 35-year clinical experience with 252 aneurysms in 168 patients. Ann Surg 234:454462 80. Lederle FA, Johnson GR, Wilson SE et al (1997) Relationship of age, gender, race, and body size to infrarenal aortic diameter. The Aneurysm Detection and Management (ADAM) Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Investigators. J Vasc Surg 26:595-601 81. Brown PM, Zelt DT, Sobolev B (2003) The risk of rupture in untreated aneurysms: the impact of size, gender, and expansion rate. J Vasc Surg 37(2):280284 82. Kent KC, Zwolak RM, Jaff MR et al (2004) Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: a consensus statement. J Vasc Surg 39:267-269 18 Hegenscheid et al. Potentially relevant incidental findings on research whole-body MRI in the general adult population: frequencies and management. EurRadiol 2012 83. Isselbacher EM (2005) Thoracic and Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms. Circulation 111:816-828 84. Davies RR, Goldstein LJ, Coady MA et al (2002) Yearly rupture or dissection rates for thoracic aortic aneurysms: simple prediction based on size. Ann Thorac Surg 73:17-28 85. Burns J, Brown R (2009) Treatment of unruptured intracranial aneurysms: Surgery, coiling, or nothing? Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 9:6-12 86. White PM, Wardlaw J (2003) Unruptured intracranial aneurysms: prospective data have arrived. The Lancet 362:90-91 87. Wiebers DO (2003) Unruptured intracranial aneurysms: natural history, clinical outcome, and risks of surgical and endovascular treatment. The Lancet 362:103-110 88. Fox AJ (1993) How to measure carotid stenosis. Radiology 186:316-318 89. Halliday A, Mansfield A, Marro J et al (2004) Prevention of disabling and fatal strokes by successful carotid endarterectomy in patients without recent neurological symptoms: randomised controlled trial. The Lancet 363:1491-1502 19