Northwestern-Miles-Vellayappan-Aff-Dartmouth

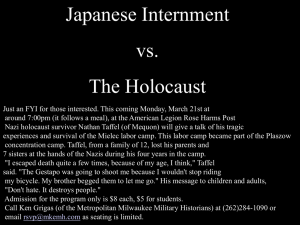

advertisement