GHD Costs and CDM

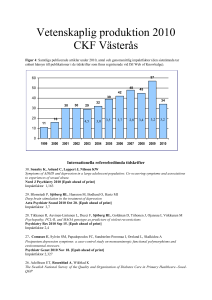

advertisement

A/Prof Terry Hannan The provision of ahistorical understanding of the relationships between clinical decision making, resource utilisation and health costs. Historical review of Clinical Decision making (CDM), resource utilisation, cost s and quality There has been an extensive discussion theme on GHDonline relating to “Costs of Care”. These discussions not uncommonly focus on one or several components of health costs and how they may be alleviated e.g. having systems “alert” clinicians on the actual costs of procedures, etc. to the patient or health reimbursement schemes. What I would like to do in this document is to look retrospectively at some of the recorded knowledge relating to these issues in the hope it may provide a better understanding of the linkages between health care technologies, clinical decision making and health outcomes. Much of what happens to one of these affects the others. In 2000 Shortliffe and Perreault displayed a graph covering the period 1956-1974 which clearly demonstrated the growth in laboratory procedures (millions) relative to the changes in hospital admission and technical personnel (Figure 1.) (1) Figure 3-early demonstration of resource utilisation with new health care technologies In 1975 Johns and Blum were able to quantify the costs of nursing units with resource utilisation and the number of clinical decisions per day which also affected patient care.(2) In numerical terms (1975 values) there was a total of $44mUS spent in the nursing units often on items < $20US each. This resulted from 2.2 million clinical decision/yr., 6,000/d or 6 decisions per patient per day. All of which impacted on patient care, costs which then generated data that iteratively affected future decision making. Based on this knowledge Blum was able to formulate a design of a hospital information system that had as its core, CLINICAL DECISION MAKING (CDM) (Figure 2.) and how this drove the resource utilisation and the generation of more data and information from the ancillary services of health care. Homer Warner of Utah documented in 1995 that the main changes to this model were around the technologies supporting medical care. Figure 2-core design of clinical data and information flow (Blum 1986) Blum also documented that the requirements for the “Business” [Red Box] of health care can be met by the data generation from CDM yet the reverse is not possible. Figure 3- Clinical Decision making models 1998 and 1999. A final confirmation of how all this links together was in a recent publication by Tierney and others (3) where the authors document the conclusion that “information and its management is care”.(4) For the purposes of education and knowledge on this topic it is worthwhile documenting the introduction to the Tierney paper. It states; “Although health care is considered a service profession, most of what clinicians do is manage information. They collect data (take a history, perform a physical examination, read reports, look up laboratory data, read x-rays), record data (write visit notes, operative reports, prescriptions, and diagnostic test results), transmit data (via telephone, paper or electronic charts, and email), process information to arrive at a likely diagnosis (or hierarchy of possible diagnoses), and initiate treatment. This initial chain of information management is then followed by additional cycles of data collection, management, and processing to monitor and adjust care. Thus, information is not a necessary adjunct to care, it is care, and effective patient management requires effective management of patients’ clinical data. According to Gonzalo Vecina Neto, head of the Brazilian National Health Regulatory Agency, “There is no health without management, and there is no management without information”. So a critical factor in the accumulation of this clinical data is to be able to store it as STANDARDISED data that can then be applied to existing KNOWLEDGE RULES and transformed into TIMELY INFORMATION MANAGEMENT [usually seconds] at the point of care. To this end we had systems that were built on Data Dictionaries such as those described in the Regenstrief(5), Beth Israel Deaconess (6) and Brigham and Womens Hospitals (MUMPS based) (7) and the Johns Hopkin System (Oncology Centre Information System)(8). What these systems demonstrated and continue to do so is that technology is not the problem it is the implementation of information management tools that will be used by the end users.(9) (Figure 4.) Figure 4- Information data base for the Regenstrief eHealth system As the demands for even larger clinical data bases has occurred [big data] newer eHealth management systems needed to be designed to support effective clinical decision making. An excellent example of this is the OpenMRS system built by Mamlin and Biondich to meet the information management needs of developing nations -40 million people living with AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa [www.OpenMRS.org ](10) Assessments of unsupported or partially supported CDM Canada 2005: Figure 5 Overuse and inappropriate use of resources in Canada 2015 Canada 1999-2009: Appropriate vs. Inappropriate use? Community Pharmacy Prescriptions-272 million (1999) to 483 million (2009). CT scanners: 198 to 465 MRI scanners: 19 to 266 from federal investments. Number of Scans: 58% increase CT scans 100% increase MRIs. (Compared to 2003) Source: www.healthcouncilcanada.ca Heather Dawson Director, Analysis and Reporting, Health Council of Canada Healthcare Policy Vol.6 No.4, 2011 United Kingdom: 1998/99 (11) 87% Unnecessary out-of-hours tests 80% Diagnostic uncertainty 79% Medico-legal protection * 66% Avoid leaving work for colleagues 71% Prevent criticism from staff (especially Consultants) 76% Lessen anxiety and reduce stress levels North America (USA): Without individualized data, physicians assume that they are performing at tolerable rates. 2000 Project HOPE—People-to-People Health Foundation, Inc. Health Affairs, March/April 2000 Medicare Pharmacy Coverage: Ensuring Safety Before Funding by Lee N. Newcomer Inappropriate use of CT scanning in pulmonary embolism. (12) Benefits of electronically supported CDM (various components of the “medical record”) Summarisation: a more effective communication tool and also in formats e.g. tabulated data, that permit better prediction of clinical outcomes.(13-15) Clinical documentation: For Example OpenNoteshttp://www.rwjf.org/en/grants/grantees/OpenNotes.html o Also Beth Israel Deaconess EHR(6, 16, 17) Compliance with care protocols : (18) Adverse drug event detection and prevention:(19-23) Resource utilisation: Addressing overuse, underuse and inappropriate use (24-27) Complex guidelines and protocols benefits : (28, 29) Clinical data versus administrative data as health care measures:(30) Open Source systems for low and middle income nations (and more recently advanced economies):(31) Figure 6 Outcomes of effective clinical decision support-RMRS and HELP systems Negative consequences of electronically supported CDM: Risks associated with Health Information Technologies (32-34) Scot Silverstein's Good Health IT and Bad Health IT http://www.healthleadersmedia.com/content/tec-288116/Scot-Silversteins-GoodHealth-IT-and-Bad-Health-IT 1. Shortliffe EH, Perreault Le, editors. Medical Informatics: Computer Applications in Health Care and Biomedicine. , 2000. (2nd edition of #4, new publisher and title).2000. 2. Johns RJ, Blum BI. The use of clinical information systems to control cost as well as to improve care. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 1979;90:140-52. Epub 1979/01/01. 3. Tierney WM., Kanter AS., Fraser HSF., C. B. A Toolkit For eHealth Partnerships in Low-Income Nations. Health Affairs. 2010;29(2):268-73. 4. Leao BF. Terms of Reference for Designing the Requirements of the Health Information System of the Maputo Central Hospital and Preparation of the Tender Specifications. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2007. 5. McDonald CJ, Overhage JM, Tierney WM, Dexter PR, Martin DK, Suico JG, et al. The Regenstrief Medical Record System: a quarter century experience. International journal of medical informatics. 1999;54(3):225-53. Epub 1999/07/16. 6. Slack WV, Bleich HL. The CCC system in two teaching hospitals: a progress report. International journal of medical informatics. 1999;54(3):183-96. Epub 1999/07/16. 7. Teich JM, Glaser JP, Beckley RF, Aranow M, Bates DW, Kuperman GJ, et al. The Brigham integrated computing system (BICS): advanced clinical systems in an academic hospital environment. International journal of medical informatics. 1999;54(3):197-208. Epub 1999/07/16. 8. Enterline J.P. LJRE, Blum B.I. A Clinical Information System for Oncology. New York: SpringerVerlag; 1989. 9. Were MC, Emenyonu N, Achieng M, Shen C, Ssali J, Masaba JP, et al. Evaluating a scalable model for implementing electronic health records in resource-limited settings. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association : JAMIA.17(3):237-44. Epub 2010/05/06. 10. Mamlin BW, Biondich PG, Wolfe BA, Fraser H, Jazayeri D, Allen C, et al. Cooking up an open source EMR for developing countries: OpenMRS - a recipe for successful collaboration. AMIA Annual Symposium proceedings / AMIA Symposium AMIA Symposium. 2006:529-33. Epub 2007/01/24. 11. McConnell AA, Bowie P. Unnecessary out-of-hours biochemistry investigations--a subjective view of necessity. Health Bull (Edinb). 2002;60(1):40-3. Epub 2003/04/01. 12. Crichlow A, Cuker A, Mills AM. Overuse of computed tomography pulmonary angiography in the evaluation of patients with suspected pulmonary embolism in the emergency department. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2012;19(11):1219-26. Epub 2012/11/22. 13. Fries JF. Alternatives in medical record formats. Med Care. 1974;12(10):871-81. Epub 1974/10/01. 14. Whiting-O'Keefe QE, Simborg DW, Epstein WV, Warger A. A computerized summary medical record system can provide more information than the standard medical record. JAMA. 1985;254(9):1185-92. Epub 1985/09/06. 15. Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831-41. Epub 2007/03/01. 16. Safran C, Porter D, Lightfoot J, Rury CD, Underhill LH, Bleich HL, et al. ClinQuery: a system for online searching of data in a teaching hospital. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111(9):751-6. Epub 1989/11/01. 17. Safran C, Rind D, Citroen M, Bakker AR, Slack WV, Bleich HL. Protection of confidentiality in the computer-based patient record. MD Comput. 1995;12(3):189-92. Epub 1995/05/01. 18. Litzelman DK, Dittus RS, Miller ME, Tierney WM. Requiring physicians to respond to computerized reminders improves their compliance with preventive care protocols. Journal of general internal medicine. 1993;8(6):311-7. Epub 1993/06/01. 19. Bates DW, Evans RS, Murff H, Stetson PD, Pizziferri L, Hripcsak G. Detecting adverse events using information technology. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association : JAMIA. 2003;10(2):115-28. Epub 2003/02/22. 20. Bates DW, Teich JM, Lee J, Seger D, Kuperman GJ, Ma'Luf N, et al. The impact of computerized physician order entry on medication error prevention. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association : JAMIA. 1999;6(4):313-21. Epub 1999/07/31. 21. Cullen DJ, Sweitzer BJ, Bates DW, Burdick E, Edmondson A, Leape LL. Preventable adverse drug events in hospitalized patients: a comparative study of intensive care and general care units. Crit Care Med. 1997;25(8):1289-97. Epub 1997/08/01. 22. Gandhi TK, Weingart SN, Seger AC, Borus J, Burdick E, Poon EG, et al. Outpatient prescribing errors and the impact of computerized prescribing. Journal of general internal medicine. 2005;20(9):837-41. Epub 2005/08/25. 23. Westbrook JI, Gospodarevskaya E, Li L, Richardson KL, Roffe D, Heywood M, et al. Costeffectiveness analysis of a hospital electronic medication management system. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015. Epub 2015/02/12. 24. Tierney WM, Fitzgerald JF, Miller ME, James MK, McDonald CJ. Predicting inpatient costs with admitting clinical data. Med Care. 1995;33(1):1-14. Epub 1995/01/01. 25. Tierney WM, McDonald CJ, Martin DK, Rogers MP. Computerized display of past test results. Effect on outpatient testing. Ann Intern Med. 1987;107(4):569-74. Epub 1987/10/01. 26. Tierney WM, Miller ME, McDonald CJ. The effect on test ordering of informing physicians of the charges for outpatient diagnostic tests. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(21):1499-504. Epub 1990/05/24. 27. Tierney WM, Miller ME, Overhage JM, McDonald CJ. Physician inpatient order writing on microcomputer workstations. Effects on resource utilization. JAMA. 1993;269(3):379-83. Epub 1993/01/20. 28. Evans RS, Pestotnik SL, Classen DC, Bass SB, Burke JP. Prevention of adverse drug events through computerized surveillance. Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care. 1992:437-41. Epub 1992/01/01. 29. Pestotnik SL, Classen DC, Evans RS, Burke JP. Implementing antibiotic practice guidelines through computer-assisted decision support: clinical and financial outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124(10):884-90. Epub 1996/05/15. 30. Evans RS, Pestotnik SL, Classen DC, Clemmer TP, Weaver LK, Orme JF, Jr., et al. A computerassisted management program for antibiotics and other antiinfective agents. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(4):232-8. Epub 1998/01/22. 31. Braitstein P, Einterz RM, Sidle JE, Kimaiyo S, Tierney W. "Talkin' about a revolution": How electronic health records can facilitate the scale-up of HIV care and treatment and catalyze primary care in resource-constrained settings. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52 Suppl 1:S54-7. Epub 2009/11/05. 32. Lee J. More technology, more risks: top hazards linked to maturing health IT market. Modern healthcare. 2012;42(45):16-7. Epub 2012/12/04. 33. Coiera E. Why e-health is so hard. The Medical journal of Australia. 2013;198(4):178-9. Epub 2013/03/05. 34. Coiera E, Aarts J, Kulikowski C. The dangerous decade. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association : JAMIA. Epub 2011/11/26.