My thoughts re rehab programme pilot

advertisement

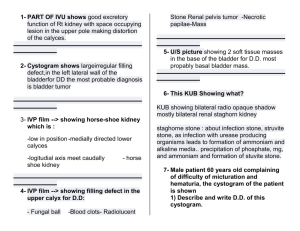

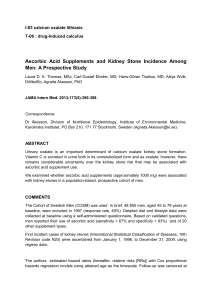

P73 MODIFICATION OF DIET IN RENAL STONE DISEASE: REVIEW OF THE EVIDENCE AND SERVICE PROVIDED AT THE ROYAL FREE CENTRE FOR NEPHROLOGY Newman, J¹, Moochhala, S² ¹Department of Nutrition and Dietetics, ²UCL Centre for Nephrology, Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust INTRODUCTION: Kidney stone disease is a relatively common condition with an estimated prevalence of five per cent in the general population with men being twice as likely as women to develop kidney stones. Historically in this Trust, dietetic referrals for kidney stone patients were ad hoc and advice primarily focused on increasing fluid intake and reducing salt intake. Following an increased number of referrals since December 2011, the current service provision was reviewed. It became apparent that our patient literature on kidney stones was out-of-date and often inconsistent with that provided by other health care professionals in the Metabolic Stone Clinic. The aim of this project was to review the current evidence base for dietary intervention, the level of input required for patients with recurrent stone disease and the expected outcome after appropriate dietary advice. METHODS: A literature search was carried out using the following sources: NHS Evidence, Cochrane Library, Medline, Embase, Cinahl, Amed using the terms below: Patient/Population/Problem Intervention Comparison Outcome Kidney stones Diet therapy None Reduction Kidney calculi Nutrition Therapy Metabolic stones Nephrolithiasis We contacted 5 renal units to ascertain what dietary advice/ service they were providing for patients with stones. We also looked at the number of referrals to the dietitian in our renal team for renal stone related advice between January 2011 to May 2012, RESULTS: Limited number of clinical trials have been conducted which evaluate the effects of various dietary treatment regimens in individuals with a history of kidney stones. Many of the recommendations are based on clinical studies of urinary measures in healthy subjects or large population studies, which correlate food intake by questionnaire to kidney stone development. Our audit of referrals in the Trust showed out of the 5 patients identified, the primary stone type was calcium oxalate in 2 patients, uric acid in 2 patients and unconfirmed in the remaining patient. The dietary advice provided was consistent with these current recommendations, which includes increasing fluid intake, reducing BMI (if clinically indicated) and reducing salt. Oxalate restriction is not always necessary (e.g. in the case of confirmed non-oxalate stones), and the degree of restriction is unclear as oxalate absorption varies with other dietary components and enteric factors. No clear or consistent guidance on the level and frequency of dietetic input required for stone patients was identified in the literature. The key clinical outcomes that should be measured as response to dietary intervention remain unclear. CONCLUSION: This descriptive project has shown that the dietary advice recommendations for kidney stone patients have not changed significantly since our last review period 6 years ago. Research has suggested some additional advice such as drawing attention to foods and fluids which may positively influence the pH, highlighting the need for regular review. In view of the current evidence, no specific additional clinical dietetic advice is indicated for our recurrent calcium-stone forming patients. Initial management is via a dietary information leaflet consistent with the published literature. Resources are best concentrated on those requiring specialist dietetic input e.g. uric acid stones, where there is a confirmed biochemical abnormality despite ‘optimised’ medical management with persisting stone recurrence. These patients are identified and managed in collaboration with the Metabolic Stone Clinic in the Trust. Even in this group, further evidence is needed to define appropriate clinical outcomes.