`Effective Feedback` – The Triple Marking Fiasco

advertisement

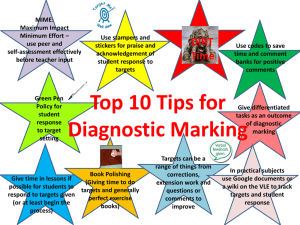

THE HIGH COST OF ‘EFFECTIVE FEEDBACK’ – THE TRIPLE MARKING FIASCO By Jack Marwood, primary teacher and education blogger Teachers are struggling under a new orthodoxy of excessive pupil writing and written feedback. With changes to Ofsted’s Inspection Handbook, inspectors are justifying their judgement on the quality of teaching by both the written work in pupils’ books and the written feedback by teachers and pupils. Senior Management Teams in schools have increased teacher workload through the imposition of extremely onerous marking policies which require teachers to work longer, and less effectively. Whilst Ofsted and the Department of Education (DfE) seem to have realised the extent of this massive workload increase, many teachers are struggling to cope with the heightened expectations currently in place. The current orthodoxy of triple marking I first wrote about this in June 2014, when I said: “It appears that ‘formative assessment’ has mutated, in the eyes of far too many OFSTED inspectors who are desperately trying to justify their subjective opinions, into a ‘preferred marking style’ requiring written feedback. In a remarkably short time we have moved to OFSTED expecting to see children given specific written ‘feedback’ for all their written work, with children responding in writing to the teacher’s writing, and then teachers responding in writing to the children’s writing. “This has imposed huge time demands on children and teachers. The best way of describing this madness I have come across is ‘Triple Marking’, as reported by cherrylkd after she had met with Elizabeth Truss: “One teacher told her about the ridiculous marking she has to do. It seems ridiculous to me anyway. Triple marking I think it was called. Teacher marks, child comments and then teacher comments on the comment. Wow! How much learning could be happening while all that marking is going on?!” As many teachers will no doubt be painfully aware, the situation is becoming much, much worse. It has got to the point where even Ofsted know that there is excessive marking, and their recent Clarifications for schools document made this very clear, stating: “Ofsted does not expect to see unnecessary or extensive written dialogue between teachers and pupils in exercise books and folders. Unnecessary or extensive collections of marked pupils’ work are not required for inspection.” Unfortunately, written Inspection reports and feedback from Inspection teams suggest that this is simply not true. School management teams continue to require extensive written feedback, and teachers are continuing to spend hours writing and responding to pupils’ written work. So where has this mountain of marking come from? As with all things in English education, new orthodoxies appear with astonishing rapidity. Teachers have clearly always marked pupils’ work, and there has been a great deal written about ‘formative assessment’. Triple marking in its current form appears to have originated in 2011, with influential documents from Ofsted and the Sutton Trust. In May 2011, Ofsted published a document called Making marking matter: St Marylebone Church of England School which codified Ofsted’s approval of a marking policy which “set the gold standard for the common features of effective diagnostic marking” and required that, “one piece of assessed work would be diagnostically marked and moderated in each unit”. In practice, this amounted to one piece of work every six weeks, “with pupils’ work marked in “green (positive) and pink (negative)” so that ‘”students had a clear understanding of how they could improve their work.” This has led to the current situation, in which this marking policy is typical: http://www.canonburyprimaryschool.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/EffectiveMarking-and-Feedback-Policy-Ratified-May-2013.pdf It’s worth reading this policy in full, but here is a summary: At least every third piece of work marked in detail. Give children opportunities to reflect on their learning needs. Use an agreed Marking Code to correct errors (which has 18 different codes). Acknowledge verbal comments with a symbol from the Marking Code. Ensure work is marked regularly and promptly after completion, to allow effective and immediate feedback to be given. Use Verbal feedback (with Marking Code symbols), Success Criteria Checklists (differentiated where possible), Peer Marking (using different coloured pencils), ‘Quality Feedback Comments’ which should help children in “closing the gap” which the children must respond to in writing, and effective marking stickers (praise, target, Green Pen questions, Peer assessment and self-assessment stickers. This policy requires teachers to give a minimum of 25 individual pieces of written feedback each week, of which 11 are written comments as follows: What is the evidence on the effectiveness of feedback? At the same time as Ofsted was publishing its Making Marking Matter, the Sutton Trust created a Toolkit of Strategies to Improve Learning. This has evolved into the Sutton Trust-EEF Teaching and Learning Toolkit, which has a section on ‘Feedback’. In common with many others, I question much of the thinking behind the toolkit, which is based on meta-analyses and effect sizes, both of which are extremely problematic. The toolkit is used to justify much of the current feedback overload, however, and it is worth examining what the toolkit has to say about the subject. Firstly, the seven meta-analyses which the toolkit uses to justify its summary of the effectiveness of feedback are surprisingly old. Two meta-analyses are 32 years old, and are summaries of even older research. In fact, four of the seven studies used by the toolkit are from the 1980s and therefore cannot be said to reflect the current situation in schools. The only meta-analysis undertaken in the last 18 years was published in 2011, and accounts for just 42 out of 931 effect sizes used in the toolkit conclusions. This is not evidence based on recent research. Secondly, the Toolkit itself suggests that the evidence it presents is only “moderate”, and is rated three out of a possible five stars. It is neither “extensive” nor “very extensive”, to use the toolkit’s own definitions. I suspect this is because of the age of the research as much as anything, but may reflect other weaknesses in the evidence presented. Thirdly, the toolkit suggests that feedback will have an average impact of “eight months progress” based on a claimed effect size of 0.62. This is a somewhat surprising claim, making large assumptions and sweeping generalisations, but it is used as an example in the toolkit’s explanation of average impact: “This means that pupils in a class where high quality feedback is provided will make on average eight months more progress over the course of a year compared to another class of pupils who were performing at the same level at the start of the year. At the end of the year the average pupil in a class of 25 pupils in the feedback group would now be equivalent to the 6th best pupil in the control class having made 20 months progress over the year, compared to an average of 12 months in the other class.” To put this claim in context, if a child were to make “20 months progress” each year during Key Stage 2, they would have advanced from (in old money) L2C in Year 2 to L5B in Year 6, or from L3 in Year 2 to L7 in Year 6. According to the government’s own figures, only 7 per cent of children who are graded L2C in maths in Year 2 managed to get to L5, and no child graded L3 has ever been graded L7 because 11 year olds are simply so much younger than a typical child capable of Level 7 maths. The claim of eight months’ progress is therefore simply not borne out by the evidence from schools. My summary of the Sutton Trust/EEF’s evidence on feedback is: Weak, out of date evidence with over stated claims of effectiveness. Triple marking costs a lot more than money There are many, many more arguments one could have about the assumptions and generalisations made about all of this. But the key issue which I want to raise is that of cost, and the hidden cost behind the Feedback frenzy with which teachers are currently dealing. According to the Toolkit, “the costs of providing more effective feedback are not high.” In fact, the Toolkit suggests that costs for feedback are “low: £2,001 to £5,000 per year per class of 25 pupils, or up to about £170 per pupil per year.” This might be a reasonable estimate of the cost to schools, but the costs to teachers are much, much higher. Teacher hours and effectiveness Teachers work extraordinarily long hours during term time. The latest Workload Survey indicates that primary school teachers work an average of 59.3 hours a week, and secondary teachers work 55.7 hours a week. This is at least eight hours a day, seven days a week. Since most teachers try to take at least one day off a week, this is almost ten hours a day for primary teachers and over nine hours a day, six days a week for those in secondary. For those who don’t teach, it’s worth knowing that most schools open from around 7am and close at 6pm. Outside of those hours, we have to work at home. And for those parents with families and other commitments outside of work, that means a lot of work late into the evening, as teachers try to manage the excessive workload which has become the norm. Of course, according to Parkinson’s Law, work expands to fit the time available. In the case of many teachers, however, the work simply has to be done. A particularly vicious version of the tragedy of the commons means that, since some teachers are able to mark every book, every week, all teachers are now expected to do so. When triple marking first became fashionable in schools, for example, I tried it out. It took hours, but it looked good. I wrote lots of feedback, and children - under clear and close supervision from me - responded. My head teacher liked what I did and used my marking as an example of what was possible, sharing it with other teachers in my school. As happened across the country, what was once a time-consuming experiment rapidly became an expectation. The problem with triple marking all the books, all the time, of course, is that it takes a very long time. One evening off, one day when you are under the weather, and the backlog mounts up incredibly quickly. Teachers then rush marking, because the expectation is that every book will have ‘diagnostic marking’, and the quality of feedback naturally drops. Very soon, written feedback becomes another bit of administration done not to help children, but to tick boxes during the next (half termly) work scrutiny. And of course, these extra hours which teachers work are not factored into the “cost of feedback”, as calculated by the Sutton Trust-EEF Teaching and Learning Toolkit. But there are many additional costs, in many different ways: In teachers’ ability to educate children in their care; in teachers’ commitment to their profession; in lost expertise as experienced teachers leave the profession; in long term teacher development as young teachers decide to get out after a few years (and don’t forget that 50 per cent of teachers are not teaching five years after training); in the loss of trust senior management teams have in their frontline staff (read this blog post to see how little teachers are currently trusted in schools). Add to this the cost to education: Children have to be taught to read and respond to ‘marking codes’; time has to be allocated to ‘Directed Improvement and Reflection Time’; and children have to be drilled to respond in the approved style for the next time an Ofsted Inspector asks them what their ‘targets’ are and how their teachers “let them know what to do next”. We’re all in this together To use a much used current phrase, we are all in this together. Teachers, unwittingly and in all likelihood with the best of intentions, have ended up adding massively to their workload. Senior Management, similarly, have added hugely to the problem. Ofsted and the DfE, as so often, appear to be at the root of it all. And we all need to recognise the folly for what it is. Marking should be something which works for a child and a teacher. It should be negotiated between teams of professionals within a school, not mandated from outside. Provided children are learning, and teachers are helping them to learn, there should be no set expectation as to what, how, the frequency, or in what colour pen feedback is given. A crisis has to be managed with brave, decisive action. Ofsted should remove all mention of marking from its handbook for a time so that teachers, schools and children can focus on learning, not administration. Jack Marwood is a primary school teacher in the north of England. He blogs about education at: http://icingonthecakeblog.weebly.com/