Canterbury Round Table

advertisement

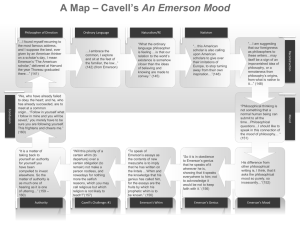

Mysticism as Intellectual Religion: Ralph Waldo Emerson as the End-Point of Origenism? Intro: A few words on Emerson (1803-82), the ‘Sage of Concord’…. We might begin by rephrasing a famous question posed by Tertullian: What has Emerson to do with Origen? Well, as it turns out, more than you would think. Let me try to be precise here: It’s not that Emerson repeatedly refers to Origen; in fact, he only mentions him once, namely in an essay on one of his absolute heroes, Plutarch… Instead of a direct reliance on Origen, what we find in Emerson are clues to the fact that he has been exposed to influence from the broader phenomenon of ‘Origenism’: 1. Emerson, the Platonist, has drunk from the same sources as Origen and his followers: Plato, Plotinus, Plutarch, Epictetus, etc. Fx concepts such as ‘soul’, ‘genius’, and ‘emanation’ and ‘participation’ figure frequently in Emerson’s writings. 2. Parallel to Origen, Emerson may be characterized as a Logos-thinker, but the rich semantic contents of logos has been distributed into a number of interrelated concepts: The ‘Over-Soul’ or God as ‘Universal Mind’; The immutable Moral Law which is incarnated in the moral sentiment; and, finally, the concept of Reason as intuitive insight – as opposed to the Understanding. 3. Probably the most important evidence to the influence of Origenism on Emerson stems from the fact of his being well versed in Cambridge Platonism, in particular the writings of Cudworth, and Cudworth appears several times in Emerson’s published works, as well as in his journals. (On the hand-out I have compiled most of this testimony to Emerson’s gread admiration for Cudworth). 1. Intellectual Religion and the Mysticism-type of Ernst Troeltsch Based on the available sources, my distinguished colleage, Alfons Fürst, has convincingly shown, that 2nd and 3rd century Alexandria provided the fertile context for the development of Christianity as an Intellectual Religon, a kind of merger between philosophy and Christianity (2 quotes). Based on this insight, I want to make the case that in Ernst Troeltsch’s The Social Teachings of the Christian Churches, the ‘Mysticism’ – type of Christianity (as opposed to the ‘Church’ and ‘sect’ type) is intended to include this kind of intellectual religion. Without going into the scholarly debate on the mysticism-type, let’s just look at the criteria put forward by Troeltsch himself in the chapter on ‘Mysticism and Spiritual Idealism’: 1. In the widest sense, says T., “mysticism is simply the insistence upon a direct inward and present religious experience”. It is found in the NT, in particular in John and Paul. This mysticism, he goes on to say, “has expressed itself in a very vital way at all periods of Church history, and particularly at all periods of criticism of tradition, of religious decline, and of new religious developments” (p. 733) 2. It is ‘an independent religious principle’ (734) aiming to restore an immediate union with God. At the same time, it is much more than just ‘experience’; in fact, in a passage that might cause us to think of Origen, Troeltsch explains how mysticism (as he conceives of it) requires ‘a general cosmic theory’: “A theory of this kind must be able to show how it came to pass that, in God, a separation between God and finite spirits could take place, and how this separation can be overcome by the very fact that finite spirits have their being within God. It shows how all that is finite proceeds from God and returns to God” (735; cf also quote on hand-out). 3. Under the heading ‘The Divine Seed’, T talks about how the theory of a universal cosmic process is also “the ultimate underlying truth in the Christian experience of salvation” – it is “the great doctrine of the Divine Seed, of the Divine Spark which lies hidden in every mind and soul, stifled by sin and by the finite, yet capable of being quickened into vitality by the touch of the Divine Spirit working on and in our souls” (738; cf. also longer quote on hand-out). 4. In particular, T. makes no secret of his fondness of Protestant mysticism which he understands as pointing to similar insights as those found in modern philosophy of religion (cf. quote on handout). The importance of this connection is highlighted by the fact that (in a famous foot-note) T reveals that his own, personal theology is of this type: “My own theology is certainly ‘spiritual’, but for that very reason it seeks to make room for the historical element, and for the ritual and sociological factor which is bound up with it” (p. 985). 5. Mysticism is a ‘radical individualism’: “In itself, this kind of spirituality fells no need for sacraments or dogmas, for a ministry or for organization” (744). 6. Tolerance toward other religious traditions (cf. quote on hand-out) 7. “Since all mysticism first arises in opposition to objective dogmas and forms of worship, it assumes in a very aristocratic way that the concrete forms of worship will continue to be the religion of the masses. It is its mission, however, to call the true children of God out of that external worship in order to lift them up into the Kingdom of God which is purely within us” (746 f.) 8. Spiritual religion as a response to the historical criticism of the Bible: “… very often the need for release from historical uncertainty led to the demand for the pure immediacy, present character, and inwardness of the evangelium aeternum, to the expectation of the Third Dispensation in which each individual, out of the depths of his own life, independently and personally, and yet essentially in agreement with others, gains his own knowledge of God” (p. 791). 9. Troeltsch notes how mysticism as spiritual religion is found in the philosophy of religion of Leibniz, Spinoza and German Idealism. And then he continues with a characterization that fits Emerson surprisingly well: “In them spirit becomes genius, and the physical is treated as an external intellectualism which is calculable and tangible. In them faith is treated as a feeling which the Presence of God effects in the soul, in which He alone and all His works can be experienced” (p. 792). Troeltsch sees here the old influence of Neo-Platonism combined with ‘the aesthetic colour of Platonism’. 10. Of particular importance is the Romantic movement and what Troeltsch calls ‘religious Romaniticsm’ which is “the source of that which the modern German Protestant of the educated classes can really assimilate – his understanding of religion in general. This is the secret religion of the educated classes” (p. 794). And, significantly, it is in this narrower context that Troeltsch refers to “the literature of the Emerson group” (p. 795) – by which, presumably, he means New England Transcendentalism. 11. In the ‘Conclusion’ to his Social Teachings Troeltsch once again touches upon the internal connection between mysticism and modernity: “Mysticism has an affinity with the autonomy of science, and it forms a refuge for the religious life of the cultured classes; in sections of the population which are untouched by science it leads to extravagant and emotional forms of piety, but in spite of that if forms a welcome complement to the Church and the Sects” (p. 994). 2. Emerson as a Paradigmatic Case of Troeltsch’s Mysticism-type 3. To What Extent is Emerson Part of the Legacy of Origenism in Western Thought? Emerson and Logos-Christology: Emerson the Unitarian has no Christology, but we do find traces of a ‘pedagogical’ soteriology. Other than that, we may interpret the connection in the following manner: In Emerson, LOGOS is partly the world-soul (God is Intellect or Universal Mind), partly Reason, by which man is able spontaneously/intuitively to grasp the divine will, which is also present in man in the form of the moral sentiment (and conscience). The element of mysticism comes to the fore when Emerson repeatedly states that ‘God is in man’.