Excerpt - Leigh Graziano

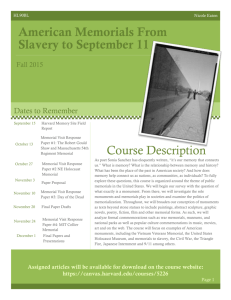

advertisement

Graziano Polyvocality, as the organizing principle, pervades the other five characteristics of living memorials. And, more than that, it is the key difference between national memorials and living memorials. National memorials are univocal and homogeneous. According to Cheryl JorgensenEarp and Lori Lanzilotti, “official expression tends to emphasize an abstract ideal that apparently does not threaten, and in many ways supports, the status quo” (152). These memorials speak a symbolic language, highlighting abstract concepts like patriotism to “promote social unity” (152). The uniform, sanctioned narrative they purport does not invite interpretation. Dwight Pitcaithley, Chief Historian of the National Park Services, adds: “Monuments, memorials, and anniversaries often are designed not to help us understand the past, but to generate support or evoke empathy with our view of the past to the exclusion of often competing views” (51). This is not to say, however, that national memorials do not interface with vernacular culture. The construction of public memory through commemorative events inevitably involves mediating between official agendas and vernacular interests (Bodnar). In fact, Bodnar argues that the Vietnam Veterans Memorial is unique in that it shows how vernacular culture can be more powerful than official interests. Vernacular culture makes use of commemorative symbols that take the form of material contributions to the wall in an effort to speak against an official narrative. Polyvocality, on the other hand, invites ongoing reinterpretation; it is the language of not only the public but official and vernacular expression as well. Roadside memorials, for example, negotiate the vernacular and the official given that most states prohibit the construction of such memorials and offer uniform “drive safely” signs to mark the spot. The result, however, is not an immediate replacement, but rather the interface of the living memorial with the state sanctioned sign, which eventually will be the only part of the memorial remaining (Figures 2 and 3). These memorials have the flexibility to change, selecting and excluding certain “voices,” views, and materials. Figure 3 illustrates that certain rhetorics, like the sign advertising for bunk beds, are 1 Graziano 2 rejected by the community and promptly removed. Living memorials demonstrate that an imposed narrative in a democratic community is highly unlikely, even if the community does intercede to edit out inappropriate contributions. As polyvocal artifacts, living memorials embrace more than the multiple authors contributing to the construction and reception of a memorial. Polyvocality also encompasses the “voices” of the various material rhetorics that compose the memorial. As a result of this complex amalgamation of authors and materials, polyvocality encourages multiple readings and makes no effort towards synthesizing those readings into one message. Gerard Hauser argues that everyday interactions and rhetorics, both official and vernacular, are inherently polyvocal. As he explains: [They reflect] a variety of voices that enter a discourse in which everyday objects, acts, and expression, such as food we eat, markets where we shop, greetings we exchange, clothes we wear, dialects we speak, and idioms we share are symbolic re-presentations of social reality. (30) In terms of living memorials, the polyvocal authorizes not only the people constructing and contributing to the memorial but also the material elements, the ephemera, to operate as rhetoric themselves. In particular, Hauser’s focus on different interpretations highlights the fluidity of polyvocality because the meaning constructed within this discourse is dependent on a changing rhetorical situation, addressing a range of exigencies. The polyvocal creates fragmentary combinations of different voices, materials, and vantage points. Rebecca Jones argues that polyvocal discourse does not create an ideology; rather, it unites “a chorus of unique voices making a purposefully dissonant song” (para. 11). And since polyvocality unites individual voices with other individual voices, it mediates the viewers’ attention between the individual and the project as a whole, thereby changing both individual and communal experiences. Graziano 3 Neither the individual voice nor the collective chorus asserts itself as supreme. Rather, they maintain simultaneously both dissonance and harmony. Polyvocality emphasizes the multimodal, networked nature of living memorials as they choreograph different rhetorics: official, vernacular, visual, material. Living memorials mediate networks of human and nonhumans agents, and as such, present a unique challenge for visitors. Visitors, regardless of which community they belong to, are asked to “read” “multiple actors, multiple compositions, multiple modalities, and multiple infrastructural resources” (Sheridan, Ridolfo, and Michel xxvii). Given rhetoric’s distribution, the rhetoric of living memorials emerges from points of intersection where these factors become proximate to each other. In this way, then, living memorials are networks of activity. The meaning of these memorials does not originate in the individual because the artifacts themselves have agency; rather, it is the collaboration of disparate voices, artifacts of various modes and communities of strangers that make up the meaning of these everyday performances. The combinations of human and nonhuman contributions make up the network of commemoration. The result is that the polyvocal nature of living memorials both organizes and disrupts meaning, all in an effort to advance such a complex rhetoric towards a shared purpose. Polyvocality, then, plays out on multiple levels because of the complexity of living memorials. Polyvocality exists in the hundreds of authors adding ephemera to the overall composition of the memorial; it exists in the way those materials speak to each other and interrupt each other. Thus, polyvocal extends an invitation for self-authorization and that invitation is accepted within the community. On a smaller level, this discursive and non-discursive discourse is dominantly visual. It includes the way the materials work together and resist each other. We must consider the way the memorial interrupts and appropriates the space it occupies, and the way that space becomes a vocal part of the memorial and its rhetoric. Space is one of the multiple modes used for everyday Graziano composing. All of these “voices” are part of the way living memorials construct meaning. In this way, polyvocal permeates the myriad characteristics of living memorials because polyvocal is inherently multimodal. In particular, it is the polyvocal nature of living memorials that results in their instability. 4