full paper - Conference of the Regulating for Decent Work Network

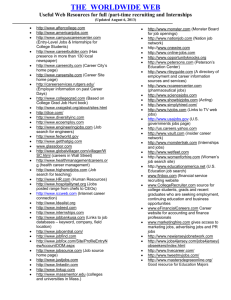

advertisement