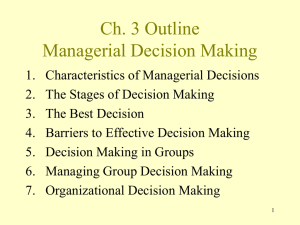

Group Size and Vigilance in North American

advertisement

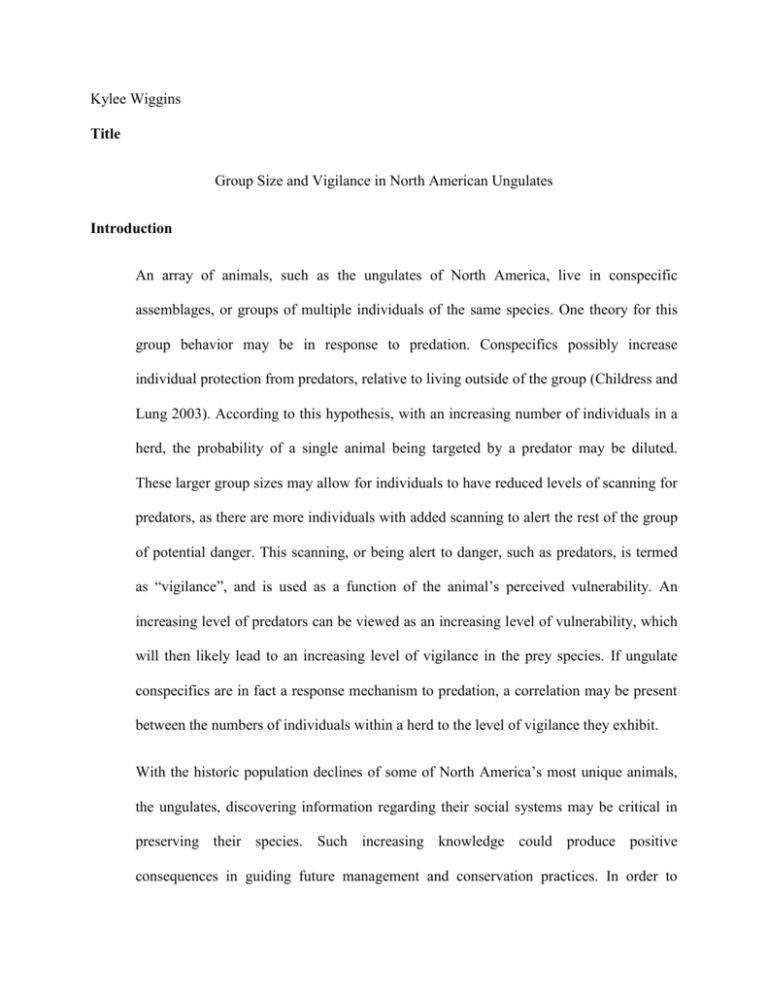

Kylee Wiggins Title Group Size and Vigilance in North American Ungulates Introduction An array of animals, such as the ungulates of North America, live in conspecific assemblages, or groups of multiple individuals of the same species. One theory for this group behavior may be in response to predation. Conspecifics possibly increase individual protection from predators, relative to living outside of the group (Childress and Lung 2003). According to this hypothesis, with an increasing number of individuals in a herd, the probability of a single animal being targeted by a predator may be diluted. These larger group sizes may allow for individuals to have reduced levels of scanning for predators, as there are more individuals with added scanning to alert the rest of the group of potential danger. This scanning, or being alert to danger, such as predators, is termed as “vigilance”, and is used as a function of the animal’s perceived vulnerability. An increasing level of predators can be viewed as an increasing level of vulnerability, which will then likely lead to an increasing level of vigilance in the prey species. If ungulate conspecifics are in fact a response mechanism to predation, a correlation may be present between the numbers of individuals within a herd to the level of vigilance they exhibit. With the historic population declines of some of North America’s most unique animals, the ungulates, discovering information regarding their social systems may be critical in preserving their species. Such increasing knowledge could produce positive consequences in guiding future management and conservation practices. In order to investigate this topic further, a study was performed at Montana’s Bison Range National Refuge by observing the behaviors of elk, Cervus canadensis; mule deer, Odocoileus hemionus; bison, Bison bison; pronghorn, Antilocarpa americana; whitetail deer, Odocoileus virginianus; and bighorn sheep, Ovis canadensis. I hypothesized that in comparing each species’ vigilance rate to their group size, there will be a decreasing proportion of vigilant to non-vigilant behavior as group size increase. This hypothesis is predicted to be explained by a group exhibiting a larger number of individuals, which will lead to an increased total level of scanning performed by the entire group, thus relieving each specific animal of an increasing fraction of essential scanning. This decreasing need for vigilance through larger herd sizes is beneficial to the animal, allowing for more time for other essential activities, such as foraging for food. Study Area The data recorded to test our ungulate hypothesis about group number and vigilance was collected at the Bison Range National Wildlife Refuge in western Montana (Figure 1). It is managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and consists of 18,500 acres, protected primarily for a bison herd of around 300 individuals. In addition to the ungulates, mammals such as mountain cottontail, Sylvilagus nuttalli; yellow pine chipmunk, Tamias amoenus; Columbian ground squirrel, Urocitellus columbianus; badger, Taxidea taxus; and muskrat, Ondatra zibethica; as well as over 220 bird species also inhabit the refuge (fws.gov). Common predators include coyotes, Canis latrans; grizzly bears, Ursus arctos; and grey wolves, Canis lupus (Childress and Lung 2003). The refuge habitat consists of prairie hills and mountains, with relatively more minor areas consisting of pine forests and wetlands. Methods During the weekend of September 20-22, 2013, students from the University of Idaho conducted scan-sampling at 5-minute intervals to document vigilance behavior of the ungulate species at the Bison Range. Students were divided into groups of 3-4, and each group observed an ungulate herd for at least 20 minutes. Herd size and the number of individuals per herd performing vigilant behavior was recorded for each scan. Vigilance was defined as the individual showing alertness to danger, and not performing other tasks, such as lying down, feeding, or walking. Observations were performed using binoculars and spotting scopes to allow scanning from a far distance, so as not to disturb the animals (which could possibly skew data, causing extra vigilant time to be recorded from the herds). In order to test the hypothesis for group size and vigilance correlation, each ungulate species’ data was analyzed separately. For each group size per ungulate species, the number of vigilant observations was divided by the number of observations of the animal performing any other behavior, which provided the vigilance rate (expressed as a percentage). Results The results consisted of vigilance rates for pronghorn, bison, elk, whitetail deer, mule deer, and bighorn sheep. In order to perform accurate comparisons between each species of ungulate, only group sizes between 1 and 37 were analyzed. The vigilance rate results were compared using a stacked line graph (Figure 2). When analyzing the line graph, there is no distinct slope for any of the species’ line graphs, concluding that there appears to be no significant correlation between vigilance and group size according to this analysis. Discussion The hypothesis that in comparing each species’ vigilance rate to their group sizes, there will be a decreasing proportion of vigilant to non-vigilant behavior as group size increases would require each species slope on the line graphs to have a distinct negative slope. Since they did not, we must reject the hypothesis. This may be due to the use of multiple groups of students recording ungulate behavior differently. Interpretations of different behaviors will have different effects on the type of data recorded, skewing data reliability. Equally important may have been due to the random levels of data per group size analyzed. For some group sizes, dozens of groups were recorded, allowing for a more accurate group size sample. On the other hand, some group sizes were only recorded a single time. If each group size were recorded and analyzed at the same rate, this might have provided a more accurate analysis. Other varying factors for group size and vigilance may include season, presence of juveniles, and breeding stage of each animal. Although this data may not have provided accurate results, increasing knowledge of these ungulates will be important for future conservation of these species. Literature Cited Childress, M.J., & Lung, M.A. 2003. Predation risk, gender and the group size effect: does elk vigilance depend upon the behavior of conspecifics? Animal Behaviour 66:389-398. U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service National Bison Range. 10 Nov 2013. <http://www.fws.gov/refuge/National_Bison_Range/wildlife_and_habitat/index.html> Figure 1. Map of the area of the National Bison Range in Montana, also displaying surrounding roads. <http://www.fws.gov/refuge/National_Bison_Range/map.html>. Accessed 10 Nov 2013. 120 Vigilance Rates of Pronghorn, Bison, Elk, Whitetail Deer, Mule Deer, and Bighorn Sheep 100 80 Pronghorn Bison Vigilance Rate (%) Elk 60 Whitetail Deer Mule Deer 40 Bighorn Sheep 20 0 1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 19 21 23 25 27 29 31 33 35 37 Group Size Figure 2. Results of pronghorn, bison, elk, whitetail deer, mule deer, and bighorn sheep vigilance rates.