Evaluation of Experimental Learning Spaces

2010

Evaluation of Experimental

Learning Spaces, University of

Leicester

Phil Wood

(School of Education)

Paul Warwick

(School of Education)

Derek Cox

(Academic Practice Unit)

10/26/2010

Evaluation Report: Experimental Learning Spaces

2

Contents

Executive Summary

Page No

3

1.0

Introduction

2.0

Higher education learning spaces in transition

3.0

Method

4.0

Results

4.1

Student and lecturer perception of the museum studies learning studio

4.2

Student and lecturer perception of the general seminar

Room

4.3

Student and lecturer perception of the Geography

Seminar Room, School of Education

5.0

Discussion of findings

5.1 Deriving a theoretical framework

6.0

Conclusion

6

7

10

15

16

20

21

23

24

27

References

Appendix 1 – Selected results from baseline questionnaire

28

30

Evaluation Report: Experimental Learning Spaces

3

Executive Summary

This report summarises the findings from an evaluation of the development of three experimental learning spaces within the University of Leicester. These learning spaces were created in 2009 and represent a refurbishment of existing rooms. The main variable separating the three rooms is the cost of their redesign and extent of modifications.

The three innovative learning spaces investigated were:

the Museum Studies learning studio (including a raised floor, a large white-wall for participants to write on, a number of state of the art ICT facilities such as Wi-Fi connectivity, interactive whiteboard, and video conferencing, and new furniture including collapsible tables and new chairs);

a general seminar room (including a plasma screen linked to a multi-media computer hub, a second set of ICT equipment with a digital projector, a glass whiteboard wall, and tip-up tables);

a School of Education seminar room (including tip-up tables, student whiteboards placed around the walls, and ICT equipment linked to a digital projector and interactive whiteboard).

The aim of this research project was focused on capturing a detailed picture of the lived experience of students and teachers using these rooms, and their reflections on working in new learning spaces. In total 54 postgraduate students and five members of staff were consulted through an online questionnaire and interviews (one to one and small group).

These rooms were found to represent, to varying degrees, spaces that were both flexible and adaptable. This flexibility was something that in general both staff and students responded towards favourably and was observed by one lecturer to ultimately result in students becoming more cohesive; acting more as a group rather than as a number of individuals. In terms of equipment, there was a general preference towards small clustered table layouts that facilitate collaborative learning approaches. All groups demonstrated a strong dislike for learning rooms being configured with just chairs and no tables.

The postgraduate students consulted expressed a clear preference for active learning approaches, particularly the use of discussion, problem solving and decision making learning opportunities. Students were extremely positive about the design of these learning spaces affording greater opportunity to adopt collaborative and active approaches towards learning.

Evaluation Report: Experimental Learning Spaces

4

Most students showed a preference for having additional information and exercises provided on a virtual learning environment to supplement their learning beyond sessions in these rooms.

This appears to suggest an expectation to expand study and learning beyond the spatial and temporal limits of a formal physical learning space, and formal face-to-face learning sessions.

In different ways each of these three rooms has changed the way in which both students and lecturers have used ICT. Positive comments were received with regard to the ICT potential of the three rooms although lecturers in their varying degrees of use of ICT in their teaching revealed the important need for adequate training in order to maximise use and to approach the less familiar resources with confidence.

A number of students commented on the positive impact these experimental learning spaces had upon their intrinsic motivation for learning, identifying positive elements to include the sense of being prized and having their ‘voice’ valued, as well as physical aspects such as the light, environmental and spacious feel of the room (particularly with regard to the museum studies learning studio).

In some cases a key factor with regard to both the staff and students’ interaction with the learning spaces seemed to be a personal sense of belonging and assumed ownership of the physical space. Where this existed, students seemed to maximise their use of what the room had to offer.

The students’ feedback provides an important insight into the complexity of their understanding of what constitutes an educational space, commenting not only on environmental and physical aspects, but also social and personal dimensions. This we would argue requires a shift in the way university lecturers commonly think about the process of learning and teaching, and their central place within it.

These provisionally positive findings for all three learning spaces make an important contribution to the current debate with regard to the apt design and sustainable function of new learning spaces in Higher Education and their impact upon student learning. This study has encountered students and staff describing their new learning spaces as ‘brilliant, enjoyable, and uplifting’ and ‘providing the opportunity to think differently’; this is something very much to be commended.

From this study we propose an innovative model for the creation of future learning spaces at the University. The DEEP learning spaces model both captures the key characteristics of a 21 st

Evaluation Report: Experimental Learning Spaces

5 century learning space and also highlights an apt design process. The DEEP learning spaces model consists of 4 elements:

Dynamic – learning spaces that have the flexibility to change in both space and time. A design process that is ongoing allowing for a flow of modification and personalisation.

Engaging – learning spaces that afford diverse and inclusive use being able to accommodate a variety of pedagogical approaches and different learning styles. A design process that takes into account flexible use and baseline environmental factors such as light, temperature ICT and spaciousness. As such, learning spaces should allow pedagogic design and use of learning resources that open the way for deeper student learning.

Ecological – a learning space that gives attention to environmental aspects. A design process that in its systems thinking approach gives attention to aspects such as sustainable procurement and ecological architectural design

Participatory – a learning space that is continually negotiated by the lecturers and students. A design process that is consultative allowing for a sense of ownership and a tailoring to the needs of both staff and students.

Recent presentation of this model to an International educational conference has led to some very positive interest and it is our aspiration that the University of Leicester will continue to find fresh avenues for applying and refining the DEEP learning space model in order to continue to offer an original and pioneering contribution in this field.

Evaluation Report: Experimental Learning Spaces

6

1.0 Introduction

With the advent of an increasingly ‘fluid’ approach to learning in higher education, represented by the development of advances such as e-learning and blended learning, the belief in the predominance of a basic, teacher centred, transmissive classroom based learning experience is no longer sustainable. There is also a developing interest in the link between learning theory and learning environments (e.g. Oblinger, 2006) which is leading to a fundamental reevaluation of approaches to learning, and the physical environments in which such interactions exist, especially within the English-speaking world. In addition, space is increasingly at a premium in a massified and resource poor sector, with a need for more inventive and efficient use of space. Similar concerns in the school sector have already led to a keen interest in the study of learning environments (Jonassen & Land, 2000; Fisher & Khine, 2006), and a fusion of the fields of physical learning space development (growing out of architecture, e.g. Dudek,

2000; Taylor, 2009), and active, constructivist learning (from educational and neurosciences research, e.g. Jarvis, 2009; Cigman & Davis, 2009), coalescing in research into ‘learning spaces’.

As part of a growing interest in the role of learning spaces, a number of studies already exist which consider the characteristics of the physical learning environment and their potential impact upon student learning both at the higher education level (e.g. Van Note Chism &

Bickford, 2002) and at school level (e.g. Woolner, 2010) as well as considering innovative and diverse designs for flexible learning contexts. This report aims to add to these debates by evaluating the development of three different learning spaces which have all been created over the past year here at the University of Leicester, U.K., and which are all refurbishments of already existing learning spaces. The main variable which separates them is the level of resources included during refitting, including addition of technology and new furniture, resulting in different amounts of money being spent on each space in an attempt to update and diversify their use. However, pedagogic aims have remained central in each case to the blend and level of refitting.

Evaluation Report: Experimental Learning Spaces

7

2.0 Higher education learning spaces in transition

Universities are currently experiencing radical and continued changes concerning beliefs about learning, trends towards a more diverse student population, and greater workload pressure on academics. However, the formal learning spaces of universities in which academics work have essentially remained static over centuries. Jamieson (2003) reflects that;

‘This institutional architecture has provided an optimum environment for prevailing teacher-centred practices - lecture supplemented by tutorial - concerned primarily with the one-way delivery of information to students.' (p. 119)

Vredevoogd and Grummon (2009) argue that as a result of a growing interest in creating learning spaces that encourage more collaborative and active approaches to learning within

American universities, there is a growing belief in the need for spaces which are both flexible and adaptable. This growing interest has come from both changes in beliefs about learning

(Long and Ehrmann, 2005), but also as a result of changing student expectations. Similar beliefs underpin major reviews within the UK and Australia. The Scottish Funding Council (2006) argues for new learning environments developed within both new buildings, and through the refurbishment of spaces which already exist. As with Vredevoogd and Grummon (2009), this belief is based on both an increasing diversity of student populations and on changing beliefs about learning processes and approaches. A number of ‘spatial types’ are proposed, giving planned flexibility in relation to learning spaces. Examples range from group teaching/learning spaces such as lecture rooms and classrooms where there is less of a focus on one point in the room and where furniture can be stacked to allow greater mobility, to peer-to-peer and social learning spaces, often informal in nature such as cyber-cafes and group rooms in libraries.

Technology is seen as central to the development of new learning spaces. Brown and Lippincott

(2003) suggest that the development of new approaches to teaching and learning linked to the rapid increase in technology across society inevitably leads to the need for conscious planning to integrate Information Communication Technology (ICT) within learning spaces. This includes the near ubiquitous appearance of wireless networking which allows for mobile computing, and an increasing movement towards students continuing their work outside of class in such social spaces as libraries, cafes and halls of residence. Punie (2007) led a workshop of 20 experts on the future of learning the role of ICT, and found that with the increasing use of a number of ICT based technologies such as virtual learning environments, blogs, wikis and podcasting, future learning spaces must take a number of different forms which not only exist as physical spaces on campus but which extend to virtual learning spaces and other physical spaces, both personal and social beyond the university campus. This suggests an increasingly complex definition and understanding of the notion of a learning space, something which would require a shift in the

Evaluation Report: Experimental Learning Spaces

8 way that university lecturers think about the process of learning and teaching, and their place within it, an issue which Punie (2007) highlights as being important;

‘ as boundaries between private, public, working and learning life become blurred, learning spaces need to be flexible enough to incorporate these shifts. Flexibility in learning styles and forms will depend on the teaching staff’s ability to incorporate such requirements into the learning curriculum, hence the importance of teacher training.' (p. 193)

With the increasing interest in providing new, innovative and flexible learning spaces within higher education which take account of rapid developments in technology, and new ideas about learning, there are a number of studies which set out factors deemed to be important in designing useful and positive learning spaces (see table 2.1)

JISC 2006

flexible

future proofed

bold

creative

supportive

enterprising

Jamieson et al 2000 Oblinger 2006

multiple use

flexibility

use of the vertical

integration of functions

maximize teacher and student control

maximise alignment of different curricula activities

maximise student access, use and ownership

design around people

support multiple types of activities

enable connections

accommodate ICT

designed for comfort, safety and functionality

reflecting institutional values

Johnson and Lomas

(2005)

building life-cycle

understanding of learning

the changing nature of technology

Net Generation

Table 2.1 Examples of design principles for learning spaces

Whilst some differences exist between the design principles advocated by different studies, there is a large degree of consistency in seeing flexibility, the inclusion of ICT, the ability to enable a number of different approaches to learning, and students as active individuals, as core design features. These central features are apparent in a number of experimental learning spaces developed in a number of countries. Radcliffe et al (2009) have created a framework for designing and evaluating learning spaces by highlighting the interplay between space, technology and pedagogy. Based on this framework, they have produced a number of questions which are used to aid in the generation of learning spaces, and once built, their

Evaluation Report: Experimental Learning Spaces

9 evaluation. Oblinger (2006) provides a number of case studies from universities across the USA and beyond, to show innovative design principles in relation to learning spaces with an emphasis on the integration of technology many of which emphasise informal and independent small group learning. The Learning Landscapes project, based in the U.K., and led by the

University of Lincoln, is another project which has aimed to consider the development of learning spaces across a number of universities in a holistic way, seeing the campus as an integrated whole, and putting pedagogy at the core, driving design . As with Oblinger’s work, a number of case studies and exemplars are presented to demonstrate the embodiment of these principles in design.

Given the extensive literature on the vision for learning spaces and the design and pedagogic principles which underlie them, there is very little evidence that changes in learning spaces impact on learning outcomes. In a review covering the learning spaces literature in higher education, Temple (2008) cites two studies which link learning spaces with performance. The

Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment (2005) state that there is an improved student performance related to new learning spaces attributed to increased student motivation, facilitation of inspiration among students, and the provision of key facilities critical to course content. However, Temple argues that the empirical evidence for these claims is uncertain. In addition, Thomas and Galambos (2004, cited in Temple 2008) state that students give a low priority to spaces use, and that lecturer preparedness is far more important to students with respect to quality of learning. Apart from the use of large-scale surveys, very little of the literature appears to focus upon the detailed, lived experience of students and lecturers and their reflections of working in new learning spaces. As a consequence, the opportunity afforded the present researchers to evaluate three small, flexible learning spaces containing different levels of innovative technology and material infrastructure was deemed to have a clear utility in extending the depth, if not the breadth, of the critical evaluation of exemplars of new learning spaces.

Evaluation Report: Experimental Learning Spaces

10

3.0 Method

In the summer of 2009, we were commissioned by one of the pro-Vice Chancellor’s at

University of Leicester with responsibility for students to evaluate a new, innovative learning space which had been designed for use from autumn 2009. This evaluation was rapidly expanded to include two further teaching rooms which had undergone varying levels of refurbishment to include innovative facilities to enable and engage with changing pedagogies.

Details of the three rooms are given below

Museum Studies Learning Studio (MSLS)

This learning space incorporates a number of innovative features, and is identified as an experimental learning space within the university. There are a number of technological inclusions, including WiFi connectivity, interactive whiteboard (controlled from a computer console at one end of the room which also incorporates DVD and audio), repeater plasma screens located around the room, a fixed camera for video conferencing facility, a suspended floor which houses a number of electrical and connection points allowing students to use laptops, and interact digitally through the plasma screens and the digital projector. These facilities can be managed from a single portable control panel which allows users to switch between, and share ideas and presentations between each other's computers.

The furniture has been chosen to allow tables to be collapsed thereby making the physical space more flexible, and the room has plenty of natural light with a neutral, crisp white colour scheme. The windows have blinds to allow control of direct light levels. Finally, one wall has been painted with a special covering which allows it to be used as a large ‘white-wall’.

Due to the need for a suspended floor, and the level of technology used, this room was expensive to refurbish, and is therefore identified as a ‘top end’ learning space.

General seminar room

Evaluation Report: Experimental Learning Spaces

11

Located in a 10970s building, this learning space incorporates a smaller number of innovations and refurbishments. When the room was fitted out in 2003/4, a suite of IT equipment (PC, data projector, VCR, CD/DVD player) was installed at one end of the room, and the furniture set out in rank format facing the data projection screen (see left-hand photo above). The upgrade of the room for the work reported here entailed a second suite of IT equipment (installed at the opposite end of the room), with a 52” plasma screen, rather than data projector. These together allowed the teaching space to be turned through 90⁰, and the plasma screen can be used as a repeater screen for the IT equipment installed at the other end of the room See righthand photo above), a glass ‘whiteboard wall’ (approx 3mx4m), and flip-top wheeled tables

(with a smaller work-top area than those originally installed), so that changing furniture layout would be easier and quicker.

The room has restricted natural light and limited outside views due to the presence of high, narrow windows.

Due to the smaller amount of technology in the room ti was not as expensive to refurbish as the

MSLS, and s therefore identified as a ‘middle range’ learning space.

Evaluation Report: Experimental Learning Spaces

12

Geography Seminar Room, School of Education

Located in a 1900s building, this learning space incorporates a small number of innovative features. Once again, there are a number of technological inclusions, including WiFi connectivity, interactive whiteboard, and a portable trolley with 15 net-books, shared with an adjacent seminar room. The interactive whiteboard is controlled from a computer console at one end of the room which also incorporates DVD and audio.

As with the other two rooms, the furniture has been chosen to allow tables to be collapsed thereby making the physical space more flexible. Natural light is good, and blinds over the windows allow for the light level to be controlled. Finally, four small whiteboards are located around the room to facilitate brainstorming and independent group work.

Due to the very low cost of refurbishing this room, it is identified as a ‘bottom end’ learning space.

The evaluation of these three learning spaces was undertaking between January and May, 2010 and included the use of surveys and interviews. A number of representative groups were included in the evaluation sample, the composition of which is given in table 3.1.

Evaluation Report: Experimental Learning Spaces

13

Museum Studies Learning

Studio

Students

MA in International

Education (School of

Education), n = 25

MA Applied Linguistics,

TESOL (School of Education), n = 18

MA in Museum Studies

(Department of Museum studies), n = 70

Lecturers

two lecturers from the

School of education, one each from the programmes identified above

two lecturers from the

Department of Museum

Studies

Students

-

General Seminar Room

PG Cert in Academic

Practice in Higher Education , all serving academics within the university n = 18

Lecturers

one lecturer from the

Academic Practice Unit

-

Geography Seminar Room

Students

PGCE geography trainee teachers (School of

Education), n= 14

Lecturers none, as lecturer is a member of the evaluation team

Table 3.1 Sample characteristics for the evaluation of the three learning spaces

Two main methods were used to gain information concerning the initial experiences and perceptions of the users of the three learning spaces:

1) Questionnaire: an online questionnaire was created to gain baseline data from the groups of students who used the learning spaces involved. This questionnaire was completed early within the evaluation cycle, and focused on background preferences and perceptions at a general level, rather than as an evaluation of the spaces themselves, and was in the form of a series of statements with responses given at a point along a five stage Likert scale. The questionnaire focused on a number of issues relating to learning and learning environments. Personal preferences relating to learning approaches were sought, such as lectures, simulations and problem solving as well as attempting to understand the importance of different learning outcomes such as passing exams, developing learning and understanding or feelings of being challenged. A number of questions were asked concerning preferences relating to physical learning

Evaluation Report: Experimental Learning Spaces

14 environments, including the layout of desks, light levels, and the flexibility of furniture.

Finally a small number of questions were asked concerning students preferences in relation to technology and learning including their use of Virtual learning environments and Web 2.0 applications.

2) Interviews: interviews were carried out at a point when students and lecturers had had opportunity to make sustained use of the learning spaces. For each room, all of the lecturers identified in the sample, plus a small number of students (typically 2 to 4) were interviewed. The lecturers were interviewed individually, and the students in small focus groups, the interviews being recorded and later transcribed. The sample was such that the lecturers interviewed had been responsible for teaching the groups of students included within the sample so that perceptions concerning the rooms could be compared. The lecturer interviews focused on reflecting on general experiences, the impact of new facilities (in particular the inclusion of increased ICT provision), the degree to which (if any) lecturers had altered their pedagogical approach, and further alterations they felt would make the learning spaces better. The student focus groups reflected on their general experiences, the degree to which they believeed their learning had been impacted by the rooms, how the rooms compared to other learning spaces they were familiar with and the further alterations they felt would make the learning spaces better.

The two methods outlined above allowed for an assessment of the lived experience of those using the new learning spaces and are the basis for the following analysis.

Evaluation Report: Experimental Learning Spaces

15

4.0 Results

The baseline questionnaire regarding learning and learning environment preferences returned a high proportion of responses from the two groups of students who had experienced learning in the generic seminar room and the geography seminar room located in the School of

Education. However, the return rates for the two groups of students who had experienced learning in the Museum Studies Learning Studio were much lower, and this has to be remembered when considering the results gained. A representative sample of results from selected questions are given in Appendix 1, and show several general patterns across all groups.

With regards to learning approaches there is clear evidence that the post-graduate students prefer active learning approaches. For example, those identifying a like for lectures and notetaking show few students from only two programmes (MAIE and TESOL) strongly agreeing with this statement, and in all cases only a minority of students signified this learning approach at agree level or above. Particularly interesting is the PG cert Academic Practice in Higher

Education group which is made up of serving academic lecturers, where only 6.2% (one person) agreed with this statement. However, approaches focusing on discussion, and problemsolving/decision-making were both far more popular with most groups, one exception being that the Museum Studies students demonstrated the same spread of opinions concerning problem-solving/decision-making as they had with lectures and note-taking. However, as with the other groups they clearly preferred learning through discussion.

The preferences for learning approaches are reflected in those concerning the outcomes of the courses followed. It is important to note that all of the groups present in the data set are postgraduates, but across all groups there was a strong belief that the most important outcome of a course was the development of learning and understanding, together with a feeling that they had been challenged. This strongly suggests that there is a link between preferences for active learning and active outcomes.

In relation to preferences concerning the physical layout of learning environments, there is again a general trend towards preferences for table layouts which facilitate active learning approaches. Most student groups show a stronger preference for rooms where tables are sorted into groups of 4-6 seats, with the possible exception of the Museum Studies students where an almost equally strong preference is shown for desks being located in rows facing in a single direction. All groups demonstrated a strong dislike for the notion of having a room with chairs but no tables, instead all students in all groups agreeing that they liked rooms where furniture could be moved around to allow different activities.

Evaluation Report: Experimental Learning Spaces

16

Finally, most students across the groups show a preference for having information and exercises provided on a virtual learning environment to supplement their learning beyond lessons. This appears to suggest an expectation to expand study and learning beyond the spatial and temporal limits of a formal physical learning space, and formal face-to-face learning sessions.

All of these baseline results are strongly indicative of a range of post-graduate student groups who prefer, and indeed have an expectation of, active learning environments and experiences, and as a consequence show preferences for physical learning environments which will support such approaches. Having gained an initial understanding of these students’ perceptions, interviews were then used to gain a deeper understanding of the initial experiences of both students and lecturers within the three refurbished learning spaces.

4.1 Student and lecturer perceptions of the Museum Atudies learning studio

The interviews carried out with academic staff who have taught within the MSLS raised a number of consistent issues were highlighted by the interviewees. All agreed about the positive impact that the physical characteristics of the refurbished space had both upon themselves and students. For example

‘It is a smart room, it’s got comfortable chairs and good tables in it, it's got a lot of light…. it's a lovely size for a group of about 18 to 25 probably, absolutely ideal. I felt my students enjoyed being there, I think they were aware of its newness, you know, attractiveness and I think it was uplifting.'

(TESOL lecturer, School of Education)

This affective element in the impact of the refurbished room was commented on by a lecturer from the MA International Education course, who commented;

‘I do think spaces have that sort of impact [affective], both positively and negatively and my feeling is always going up into the room ‘Oh I'm going to work in that room’ and the realisation that I might not be working in that room has left me on occasion totally depressed…… it's also something about familiarity because I've actually been in there quite a lot and it's a nice big light space and that is good.’

Technology is also seen as a big element of the room, and this is where some of the views of the lecturers begin to diverge. For those who are confident about their use of technology it is clear that the room affords a great deal of opportunity. One Museum Studies lecturer (who also played a major role in developing the specification for the learning space) was responsible for

Evaluation Report: Experimental Learning Spaces

17 teaching a media-orientated unit in the room with five students, and is very pleased with the high level of interactivity that the learning space allows. This includes a near ubiquitous use of

WiFi for learning activities with laptops allowing minute by minute use of the Internet to support discussion. The same lecturer has also used video conferencing as a way of augmenting learning opportunities for students. As such, this lecturer feels that within this particular course the atmosphere has almost been one of a professional meeting rather than a teaching session.

Two lecturers from education-based courses were both willing to use some of the basic technology within the room, particularly the digital projector and computer for use with

PowerPoint, and also the use of audio for specific work on language dialects. However in both cases, the lecturers felt conscious that they were using only a small amount of the technology available, although neither suggested that this made them particularly uncomfortable.

However, one of the lecturers felt that there might be an implicit redirection in pedagogies through the enforced absence of certain, more traditional facilities, for example

‘I notice that there wasn't a flip chart, which didn't exist there at the very beginning.

It was as if there was a diktat from upon high saying whatever you do don't bring in anything all-fashioned into this room and we were funnily enough told that an OHP

[overhead projector] would never find its way into the room.'

These feelings led both lecturers and students to suggest some form of training to help them understand the use and utility of the various technological elements of the room so that they could feel more confident in their use. This is obviously one aim for the Museum Studies lecturer who helped design the room, who commented;

‘ I wanted it to be kind of this flexible white room and you just don't notice the technology is there….. I want the room to be seamless, I want the room to be a bit dull, I want the room to just seem like a white room and I think the more the technology can disappear and the easier it is to use for colleagues the better.’

One feature of the room that does appear to have been very well received is the large whitewall. Both Museum Studies lecturers are explicit about the central importance of this element of the room in helping to generate a creative and interactive environment, to the extent that one of the lecturers suggested that;

‘…even if there wasn't WiFi, even if there weren't boxes in the floor, even if there wasn't a movable tablet, even if there wasn't a video camera and a digitiser and so on and so on, just having a wall that is 15 foot long and 8 foot high that you can write on is brilliant.’

Evaluation Report: Experimental Learning Spaces

18

Whilst one of the education lecturers has made use of the wall, both education lecturers had felt uncertain about writing on the it, concerned that they might not be using the correct pens.

This had acted as a barrier to pursuing greater use of this resource.

All lecturers identified the MSLS as being extremely positive for pursuing and developing group work, to the extent that for much of the work by Museum Studies students this appears to have been the main pedagogical approach. Also, it was agreed that the various elements of the new room sent an important message to the students who were using it;

‘ it's a pleasant environment, it says the university cares about the experience you are about to have. It's about light and it's about temperature and it's about furnishings and then it's about I think tools, you know learning technology.’

(Museum Studies lecturer)

Therefore, the overall experiences of the lecturers who have used the MSLS have been positive, whilst also suggesting particular issues such as training needs to be addressed. The students reflected these perceptions closely. Students from the MA in International Education highlighted the high level of technological inclusion, the very spacious nature of the room, and were very appreciative of the active learning approaches which the room appeared to afford.

One example of this was the capture of ideas in group discussion using the interactive whiteboard. This allowed students to be involved in the discussion, and to think about and consider the issues of interest, rather than needing to take notes, a very different experience for some. As one student commented;

‘In my country it is very traditional classrooms without a TV, without the interactive whiteboard. What you can do is write down the notes because you are afraid that it is gone, but you can't be thinking, because the teacher is talking all the time.

Because you just want to keep notes and the teachers may be teaching to quickly or too slow whatever. I think it is different, very different for me.’

These sentiments were also reiterated by the MA Applied Linguistics TESOL group, who also highlighted the nature and extensive degree of technology, and who also commented upon the quality of the furniture and the brightness of the room. Individuals in both groups commented positively about the trees and vegetation which grew directly outside of the room and which could be easily seen from inside. Finally, both of these groups commented on the utility of the plasma screens which in the case of the education sessions had been used as repeaters for the main PowerPoint presentations shown through the digital projector. In both cases, the repeated information was seen as invaluable given that for the majority of students English is a second language and having a screen close by made reading information far easier.

Evaluation Report: Experimental Learning Spaces

19

The Museum Studies students again reiterated many of the ideas and sentiments expressed above. However, an important additional component of their reflections was the use of the

MSLS outside of formal learning sessions. All of the students had experience of working on group projects which needed to be developed outside of lectures. Over a period of time, groups met informally and often connected their own laptops directly to a plasma screen to help with group discussion. There was a clear sense of ownership voiced by the students who came to prefer using this space to others available in the university, for example the library. As one

Museum Studies student commented;

‘I think it has definitely been helpful for the group project, because half the time in the library the screens don't work and if it's a busy exam period its fall and you do have to do the group work one way or another, and my group had for instance two people who commuted every day so it's really helpful if there is a central space where you can come and work together.'

The Museum Studies students also used the MSLS as a base for some exercises during formal teaching sessions. In these cases students worked in groups and used the room as a central point whilst moving out across the department to collect information and develop solutions to problems. This shows the use of the learning space as flexible and complex and shows how some elements of learning are framed as clearly extending beyond the bounds of this single room.

The above perceptions of students together with responses from lecturers, suggests an unintended, but perhaps important issue when designing new learning spaces. The MSLS is a generic learning space within the university, meaning that it is not ‘owned’ by any particular department. However, because of its physical location within the Museum Studies Department there is some evidence of assumed ownership, especially by students, which may mean that the learning dynamic is different for groups from this department when compared to others who have to enter a social space which they identify as belonging to ‘the other’. It is interesting that one Museum Studies student commented when asked if they felt that with the room being where it was it was more their space that;

‘Yes, because it's in our department, and other departments don't come here so we use it when we are here, especially after they allowed us to book it outside of class time.'

The interviews concerning the MSLS show that all concerned have generally found the room to be an extremely positive learning space with ample opportunity to aline learning activities with expressed student preferences, supported by a wide range of technology which, together with

Evaluation Report: Experimental Learning Spaces

20 the physical attributes of the room, provide for a large degree of flexibility. There is some suggestion, especially amongst some of the lecturers interviewed, that there will be a continued development and negotiation between them and as they become more confident in its use. However, the newness, the light, the furniture and technology are all suggestive of a message to students that the university is interested in the quality of their learning and their development academically.

4.2 Student and lecturer perceptions of the General Seminar Room

The General Seminar Room is used by academic staff from the Academic Practice Unit to undertake the PG Cert in Academic Practice in Higher Education which must be completed by all new lecturers, focusing on their practice as teachers. An interview with one of the lecturers from the Unit clearly demonstrates that the reorientation and refurbishment of the seminar room has had a fundamental impact on both her teaching and on the learning of students who complete the course. By having more than one focus in the room, through the introduction of a glass writing panel and plasma screen, the tables are often re-orientated to foster group work when compared to the traditional use of the room which tended to lead to tables in rows. As a result the lecturer believes that students act more as a group rather than a number of individuals. The tables are also collapsible and allow a greater number of configurations to be used for different activities, something that was more difficult before refurbishment. As the lecturer commented;

‘…..so one of the benefits of that room bizarrely is that it gives you the chance to be very different in terms of configurations so that people can see two very different learning spaces within that same room.’

Given the nature of the course focusing on professional practice in lecturing, the refurbishment of the room and the extra flexibility that it affords has also become a learning opportunity in its own right as there are explicit discussions concerning the configuration of space and its relation to different forms of activity. There was far less consideration during the interview about technology, as there is far less present than in the MSLS. However the glass writing wall was considered at length and has obviously made a large difference. When groups feed back ideas, the lecturer identified the opportunity for several people to note ideas at any one time, thereby making feedback far more efficient, and leading to more time for discussion rather than note taking.

One student, a university lecturer who is currently on the PG Cert course, was extremely positive about the nature of the new room. The glass white board was seen as motivating students’ learning in a number of ways leading to a number of creative opportunities. In

Evaluation Report: Experimental Learning Spaces

21 addition, the student identified an emotional benefit saying that the room now feels as if some care has been given to it, leading to a much greater feeling of being treated as a professional;

‘It seems ridiculous, but it is part of that whole climate of feeling more professional, in part to do with the PG cert because you are trying to fit it in around everything else, because the room was really a bit grubby it really needed to be painted. It feels more just as if the university values the fact that you are fitting it in, because there is quite a ground swell of resentment against the PG cert, mostly because it needs a bit of care. So the room has an impact.'

One element which is criticised by the student is the size of the tables which are now in the room. They argued that the tables are too big and as a result some of the new fluidity of the space is lost although, the tables present have recently been replaced and are already smaller than standard sized tables. With smaller tables, the space would become more flexible and would also allow for a greater number of different activities to be undertaken at any one time.

However, even given this particular problem the student believes that people are now working more closely together as there is a greater focus on collaboration which makes the learning experience more positive. Again, the student commented that;

‘…..it feels more collaborative. That's a lot to do with the fact that you’re brought together, and I've missed lots because I've been teaching lots. The times I've been this term with the room altered seems to me that it has been more purposeful, more cohesive in terms of how people are interacting with each other. Before you were taught in the corridor bit and the coffee was at the back so you were pushing past people all the time where as now it feels slightly more spacious and the coffee goes in the middle. I know it sounds stupid but it creates more of a circle feeling, so you feel as if you are part of a circle rather than being isolated.’

The evidence from both the lecturer and student suggest that whilst technology is not at the forefront of their thinking in relation to the refurbishment of this space, unlike the MSLS, the introduction of movable furniture, and a glass writing wall have created the opportunity for a much more flexible and group orientated learning space. As with the MSLS, the other major impact seems to be that the process of refurbishment in its own right has led to a clear cultural message that the university values the learning of students by creating a modern, flexible learning space in which they can work.

4.3 Student and lecturer perceptions of the Geography Seminar Room, School of Education

This learning space was refurbished during the summer of 2009, being devised by one of the authors of the current paper in an attempt to facilitate a coherent blended learning approach

Evaluation Report: Experimental Learning Spaces

22

(Wood, 2010), part of which was the development of a more active learning orientated face-toface element to the course. Use was made of an interactive whiteboard to build group generated notes which were then saved and made available on the course virtual learning environment for later use and review by students. Folding tables were also introduced to the room, and at the beginning of major activities the students were asked to configure the room in whatever way they felt appropriate. Because the room is small, and due to restrictions in funding, it was not possible to introduce a writing wall as exists in both the MSLS and the

Generic Seminar Room. Instead, small white boards were positioned at four points around the room which could then act as foci for group work. In the author’s opinion the resultant learning space whilst very cheap to create was very flexible and allows for a number of activities to occur which had not previously been attempted.

The students were generally very positive about the opportunities available to them in the room. One student commented;

'I think the whole room is brilliant…… I don't know if it is relevant but the white boards in the corners I have thought of using when I start teaching, because it is such a good idea, it is such a simple idea that to have them all around the walls if you are asking kids to do group work, then they can show you their ideas and that kind of thing. So it has given me ideas about the classroom environment that I can follow up.’

Another student commented;

‘The white boards, such a simple idea but you don't really have that, I never had that in university or in sixth form, or at school and that is a real bonus. It is something simple, quick, easy, easy to manage, easy to use and can be used for multiple reasons.’

The tables are also seen as a great benefit in making the room more flexible and allowing a number of activities to occur with relatively easy reorientation of the room. The use of the interactive whiteboard to make group generated notes has also had a positive impact for some who feel that they can focus on listening and thinking as opposed to writing. The major advantage of the space is seen as being its flexibility and the fact that many of the positive developments in other, more expensive rooms, are essentially present but in a simplified state.

The only negative comments concerning the room was that it is sometimes too hot, the unfortunate result of a central heating system which is approximately 70 years old.

Evaluation Report: Experimental Learning Spaces

23

5.0 Discussion of findings

The results from all three rooms show a clear link between post-graduate student preferences for active and interactive learning spaces and experiences, and the rooms which have been created. Technology is an important element in these rooms, but is clearly seen as being an aid rather than an end in itself. The one facility which is additional to the rooms as previously constituted and which has had the greatest impact for both students and lecturers is the addition of writing walls or white boards. These appear to be seen as creative opportunities for group discussion and group activity work and together with foldable or collapsible tables appear to be central to the change in orientation of the learning spaces analysed.

Two potential issues need to be considered to ensure that the learning spaces are used to their full potential. Firstly, it is clear that in some cases lecturers may feel alienated if new technologies are introduced with little or no consideration of the media which they are replacing. For some lecturers this may cause pedagogical issues which need to be considered and rectified. The second issue which appears to occur from the results of the study is that the wider physical location of a learning space may impact upon how different groups use that space. It is clear in the case of the MSLS that its physical location within the Museum Studies

Department has led to a heightened feeling of ownership, particularly amongst the student body. It is unclear from interview evidence whether the reverse is true of other students, such as those entering from the School of Education, but if such cultural norms begin to develop it may inhibit some of the flexibility which the room is capable of offering for some groups.

However, it is clear from the results that in all three cases the refurbishment and use of the new learning spaces has been predominantly positive.

The growing literature focusing on changing approaches to pedagogy within higher education, and the need for resultant changes in learning spaces, emphasises the need for flexibility, creativity, the accommodation of ICT and an underlying understanding of learning as a process

(for example Vredevoogd and Grummon, 2009; Jamieson, 2003; Jamieson et al, 2000). The results from the present study suggest that the spaces which have been created meet all of these criteria. This is particularly interesting given that they were all developed with widely varying availability of funding. Some technological features might be seen as being almost a

‘base-level’ degree of provision, including the presence of WiFi connectivity, digital projector and interactive white board provision, and DVD and audio players. However, in the present work both lecturers and students found the presence of mobile furniture and opportunities to develop written ideas in a collaborative medium just as, if not more, important. The results also strongly suggest that the provision of flexible learning spaces have greatest utility when the discussion leading to their creation is focused on pedagogy and a deep understanding of how

Evaluation Report: Experimental Learning Spaces

24 lecturers and students together navigate the learning experience. It is certainly not the case that large budgets used to create technologically rich learning spaces will, by definition, create positive and constructive learning experiences.

One additional issue which arises from the interviews undertaken for this research can be emphasised by the degree to which students and lecturers could or could not discuss the rationales behind the changes made, and how those rationales worked together as a coherent system. One lecturer from the Museum Studies Department could discuss in depth the changes made to the learning space in that department. He gave clear reasons for the inclusion of new ideas and facilities and his use of those new facilities. The same can be said for one of those involved in the current research who was responsible for developing the Geography Seminar

Room in the School of Education. If greater understanding and critical development of learning spaces is to be made, these observations suggest that design and innovation should be more democratic with both students and lecturers being more widely consulted and included in the development of learning space specifications and design.

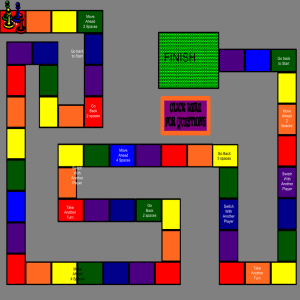

5.1 Deriving a theoretical framework

The differing experiences of both lecturers and students suggest that within any given learning space there is a constant negotiation concerning pedagogy and media. These will differ between lecturers, but will also change and evolve over time for any given group and lecturer.

Therefore, learning spaces need to be seen as dynamic not only spatially but also temporally.

Radcliffe et al (2009) offer a design and evaluation framework based around the interaction of pedagogy, space and technology. These three variables are seen to interact and determine the nature of the resultant learning spaces. Given the present evaluation of students and lecturer experiences, we tentatively suggest an alternative model for considering the design, but more importantly the evolving relationships and pedagogies within new learning spaces, what we refer to as DEEP learning spaces (see Figure 5.1).

Learning spaces need to be seen as extremely dynamic in nature. This means that they should be seen as constantly changing in both space and time. Massey (2005) makes the case for seeing space as being socially constructed and therefore constantly changing. However, this can only happen if considered in relation to time and therefore we must see learning spaces as inherently flexible and dynamic as the relationships, activities and personal histories of both students and lecturers change and evolve. In designing learning spaces and in assessing their long-term development these issues need to be taken into account.

•In space

•In time

Evaluation Report: Experimental Learning Spaces

25

•environment

•pedagogy

•multiple learning approaches

Dynamic Engaging

Participatory Ecological

•co-constructivist

•consultative

•systems approach

•sustainable

Figure 5.1 Outline schematic of elements of DEEP learning spaces

Learning spaces also need to be engaging. This includes the environments in which learning takes place, and there is clear evidence from the present research that a well considered, modern and clean environment with suitable light, temperature and furniture becomes central in engaging students in their learning. The environment must also be considered in relation to the pedagogies which are used by lecturers, themselves dynamic due to changes over time as the result of changing experiences. By developing engaging pedagogies through multiple learning approaches within engaging environments the learning space becomes more learning orientated. Again, evidence from the current research suggests that where both environments and pedagogy are engaging the learning experience of students is more positive.

Ecological learning spaces should be sustainable at a practical level. This means that the inclusion of technology needs to be carefully considered, as well as making sure that choices in furniture and other basic elements of a learning space such as paint, lighting etc have been considered for their sustainability and longevity. Ecological learning spaces should also be considered through a systems approach which means that not only all elements of the space itself, including the physical, technological and human elements need to be considered, but also the relative positioning of the learning space in relation to other available physical spaces (both formal and informal) and virtual spaces such as virtual learning environments and Web 2.0

Evaluation Report: Experimental Learning Spaces

26 applications. Again, the results from the current research suggests that where these various elements have been explicitly linked the flexibility and enrichment of learning is deeper.

Participatory learning spaces are those where the environment, learning and relationships are continually negotiated, both formally and informally, by the lecturers and students. This closely aligns participatory learning spaces with the notion of dynamism in time and space. In their creation both staff and students need to be consulted in order to facilitate a sense of ownership and belonging. Participatory learning spaces, in being co-constructivist must also take account of the needs and development of lecturers, ensuring that they have the opportunity and time to consider and discuss the development of their own practice.

We suggest that it is by considering these elements of the learning experience and the environments in which they occur that not only critical design of learning spaces can develop, but continued discussion and debate can take place which ensure that the learning spaces continue to evolve and regenerate long after initial physical refurbishment.

Evaluation Report: Experimental Learning Spaces

27

6.0 Conclusion

In conclusion, the literature on higher education learning spaces in recent years has made a strong case for flexible and creative physical learning spaces. The research here suggests that this change need not be expensive and related to large allocation of resource. With a small number of physical changes, and a clear rationale concerning pedagogy, new learning spaces can make a large difference in the experiences of both lecturers and students. However, we would go further by suggesting, through our tentative DEEP learning model, that a more complex systems approach which continues to consider the pedagogical and spatial changes in spaces once refurbished can continue to evolve new and dynamic learning opportunities.

Practical Implications

The following points are the main practical implications for the design, development and evaluation of learning spaces which emerge from the current research:

pedagogy must be central to the design, development and use of learning spaces;

spaces need to be flexible to allow for different pedagogical approaches to be aided by their design. This means that more ‘traditional’ approaches to teaching and learning should be equally applicable as more innovative pedagogies;

diff levels of ICT and infrastructure input have been strongly vindicated – successful learning spaces do not always require a wide spectrum of technological inputs;

white walls are a central element of learning space design where possible;

technology must be implemented in a way that is enabling for lecturers and learners;

in the design phase of learning space development, stakeholders need to be consulted to ensure that the resultant space provides a positive experience for both lecturers and students;

careful planning and use of new furniture and decoration can play a central role in making a learning space more flexible;

the design of learning spaces should take the level of environmental sustainability into account.

Evaluation Report: Experimental Learning Spaces

28

References

Brown, M.B. & Lippincott, J.K. (2003) ‘Learning Spaces: More tan Meets the Eye’ EDUCAUSE

Quarterly, 1, pp.14-16

Cigman, R. and Davis A. (eds.) (2009) New Philosophies of Learning Chichester, Wiley-

Blackwell

Dudek, M. (2000) Architecture of Schools: The New Learning Environments London,

Architectural Press

Fisher, D. and Khine, M.S. (2006) Contemporary Approaches to Research on Learning

Environments New Jersey, World Scientific

Jamieson, P.J.; Fisher, K.; Gildng, T.; Taylor, P.G. & Trevitt, A.C.F. (2000) ‘ place and space in the design of new learning environments’ higher education research and development, 19 (2), pp.221-237

Jamieson, P. (2003) ‘Designing More Effective On-campus Teaching and Learning Spaces: A Role for Academic Developers’ International Journal for Academic Development, 8 (1/2), pp. 119-133

Jarvis, P. (2009) Learning to be a Person in Society, London, Routledge

JISC (2006) Designing spaces for effective learning: a guide to 21st-century learning space

design , Bristol, HEFCE

Johnson, C. & Lomas, C. (2005) ‘Design of the Learning Space: Learning and Design Principles’

Educause Review, July/August. pp. 16-28

Jonassen, D.H. and Land, S.M. (eds.) (2000) Theoretical Foundations of Learning

Environments New Jersey, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

Long, P.D. & Ehrmann, S. C. (2005) ‘Future of the Learning Space: Breaking Out of the Box’

Educause Review, July/August. pp. 42-58

Massey, D. (2005) For Space , London, Sage.

Oblinger, D.G. (2006) Learning Spaces, Washington D.C., Educause,

Punie, Y. (2007) ‘ Learning Spaces: an ICT-enabled model of future learning in the knowledgebased society’ European Journal of education, 42(2), pp.185-199

Evaluation Report: Experimental Learning Spaces

29

Radcliffe, Wilson, Powell, and Tibbetts (2009) Learning spaces in higher education-positive

outcomes by design University of Queensland

Scottish funding Council (2006) spaces for learning: a review of learning spaces in further and

higher education

Taylor, A. (2009) Linking Architecture and Education: Sustainable Design of Learning

Environments, Albuquerque University of New Mexico Press

Temple, P. (2008) ‘ learning spaces in higher education: an under-researched topic’ London

review of education, 6 (3), pp. 229-241

Van Note Chism, N. & Bickford, D.J. (2002) ‘The importance of physical space in creating supportive learning environments’ New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 92 (Winter)

Vredevoogd, J. & Grummon, P. (2009) ‘ survey of learning space design higher education’ presented at the 44th annual, International conference of the Society for college and university planning, July 19-22, 2009, Portland, Oregon

Woolner P. (2010) The Design of Learning Spaces. London, Continuum

Evaluation Report: Experimental Learning Spaces

30

Appendix 1 – Selected results from baseline questionnaire

I like teaching approaches which focus on discussion

I like teaching approaches which focus on lectures and note-taking

I like teaching approaches which focus on problemsolving and decision-making.

The most important outcome of a course is passing an exam or other assessment well

The most important outcome of a course is the development of learning and understanding

The most important outcome of a course is feeling that I have been challenged

Strongly agree

Agree

Neither agree or disagree

Disagree

Strongly disagree

Strongly agree

Agree

Neither agree or disagree

Disagree

Strongly disagree

Strongly agree

Agree

Neither agree or disagree

Disagree

Strongly disagree

Strongly agree

Agree

Neither agree or disagree

Disagree

Strongly disagree

Strongly agree

Agree

Neither agree or disagree

Disagree

Strongly disagree

Strongly agree

Agree

Neither agree or disagree

Disagree

Strongly disagree

0

0

3

4

0

0

0

4

2

2

3

3

1

1

2

3

1

1

2

5

0

1

0

1

0.0%

0.0%

50.0%

25.0%

25.0%

0.0%

37.5%

50.0%

0.0%

0.0%

MAIE & TESOL

MSLS

25.0%

62.5%

0.0%

12.5%

0.0%

12.5%

25.0%

37.5%

12.5%

12.5%

37.5%

37.5%

12.5%

12.5%

12.5%

37.5%

25.0%

12.5%

25.0%

0.0%

1

3

2

1

2

0

0.0%

0.0%

42.9%

14.3%

42.9%

0.0%

28.6%

71.4%

0.0%

0.0%

Museum Studies

MSLS

14.3%

57.1%

1

4

28.6%

0.0%

0.0%

0.0%

2

0

0

0

42.9%

42.9%

14.3%

0.0%

0.0%

42.9%

42.9%

14.3%

0

3

3

1

3

3

1

0

0

0

2

5

0

0

0

3

1

3

0.0%

14.3%

85.7%

0.0%

0.0%

0.0%

0

1

6

0

0

0

0.0%

0.0%

37.5%

12.5%

50.0%

0.0%

75.0%

25.0%

0.0%

0.0%

Geography PGCE

D107

25.0%

62.5%

2

5

12.5%

0.0%

0.0%

1

0

0

0.0% 0

37.5%

25.0%

12.5%

25.0%

37.5%

62.5%

0.0%

0.0%

3

5

0

0

3

2

1

2

0

0

6

2

0

0

0

3

1

4

0.0%

37.5%

62.5%

0.0%

0.0%

0.0%

0

3

5

0

0

0

0.0%

0.0%

6.2%

43.8%

37.5%

12.5%

43.8%

56.2%

0.0%

0.0%

PGCert

SB001

18.8%

75.0%

6.2%

0.0%

0.0%

0.0%

6.2%

43.8%

37.5%

12.5%

18.8%

75.0%

0.0%

6.2%

0.0%

18.8%

62.5%

18.8%

0.0%

0.0%

0

3

10

3

0

0

0

2

7

9

0

0

0

1

7

6

3

12

0

1

1

7

6

2

3

12

1

0

0

0

I like working in a room with desks in rows, facing the front of the room.

I like working in a room where the desks are in groups of 4-6 seats.

I like working in a room with no tables, only chairs

I like working in a room with lots of light

I like to work in a room where furniture can be moved around to allow different activities

I like to have information and exercises provided on virtual learning environments (e.g.

Blackboard, WebCT) to supplement my work in lessons

I like to use Web 2.0 applications such as blogs and wikis etc

Strongly agree

Agree

Neither agree or disagree

Disagree

Strongly disagree

Strongly agree

Agree

Neither agree or disagree

Disagree

Strongly disagree

Strongly agree

Agree

Neither agree or disagree

Disagree

Strongly disagree

Strongly agree

Agree

Neither agree or disagree

Disagree

Strongly disagree

Strongly agree

Agree

Neither agree or disagree

Disagree

Strongly disagree

Strongly agree

Agree

Neither agree or disagree

Disagree

Strongly disagree

Strongly agree

Agree

Neither agree or disagree

Disagree

Strongly disagree

0.0%

12.5%

37.5%

37.5%

12.5%

0.0%

100.0%

0.0%

0.0%

0.0%

0.0%

0.0%

0.0%

62.5%

37.5%

12.5%

50.0%

25.0%

12.5%

0.0%

50.0%

50.0%

0.0%

0.0%

0.0%

25.0%

75.0%

0.0%

0.0%

0.0%

0.0%

37.5%

50.0%

0.0%

12.5%

Evaluation Report: Experimental Learning Spaces

31

0

0

1

3

2

1

0

4

3

2

4

1

0

0

0

0

1

4

1

1

4

2

1

0

0

0

0

2

0

0

3

4

2

2

1

0.0%

0.0%

0.0%

0.0%

0.0%

57.1%

42.9%

28.6%

57.1%

14.3%

57.1%

28.6%

14.3%

0.0%

14.3%

57.1%

14.3%

14.3%

0.0%

0.0%

42.9%

57.1%

0.0%

0.0%

0.0%

28.6%

28.6%

28.6%

14.3%

0.0%

0.0%

14.3%

42.9%

28.6%

14.3%

0

0

3

4

0

1

0

5

3

1

4

2

0

0

0

0

0

8

0

0

1

3

3

1

0

0

0

2

1

0

4

4

6

0

0

0

1

5

2

0

0

0

3

2

4

3

1

0

0

1

2

0

6

2

0

3

0

4

1

0

0

0

5

0

0

6

2

3

0

0

0.0%

0.0%

0.0%

12.5%

25.0%

37.5%

25.0%

50.0%

37.5%

12.5%

37.5%

0.0%

50.0%

12.5%

0.0%

75.0%

25.0%

0.0%

0.0%

0.0%

75.0%

25.0%

0.0%

0.0%

0.0%

62.5%

37.5%

0.0%

0.0%

0.0%

12.5%

62.5%

25.0%

0.0%

0.0%

0

2

3

4

7

0

0

9

2

8

7

1

0

0

3

2

4

7

5

0

2

1

10

3

0

0

0

2

0

0

9

7

10

2

2

0.0%

0.0%

0.0%

18.8%

12.5%

56.2%

12.5%

50.0%

43.8%

6.2%

12.5%

6.2%

62.5%

18.8%

25.0%

43.8%

31.2%

0.0%

0.0%

0.0%

56.2%

43.8%

0.0%

0.0%

0.0%

12.5%

62.5%

12.5%

12.5%

0.0%

12.5%

18.8%

25.0%

43.8%

0.0%

Evaluation Report: Experimental Learning Spaces

32