Dr. Deirdre Madden, UCC, opening statement

advertisement

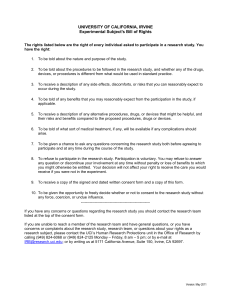

1 14 November 2013 Opening statement by Dr Deirdre Madden, UCC. Thank you for the invitation to speak to the Committee today. My background is as a Senior Lecturer in Law in UCC specialising in medical and healthcare law, but I have also been involved in the area of medical ethics and patient safety for many years. I understand that this session of the hearings is dealing with dying in hospital and therefore I will focus my submission on issues arising in this context. Although most of us would prefer to die at home, it is unfortunately not always possible for various reasons. A hospital environment can often be a busy, noisy, crowded place to die with too little time and space given to privacy and dignity of the person. Bad news can be delivered in wards with other patients overhearing from behind the bed curtain; families can wait anxiously for hours to catch a quick word with a busy consultant; patients are often left wondering what is happening to them. I am not going to speak about the physical environment in which people die as I understand the Committee has already heard submissions on this topic. I would however like to speak about the duty of care owed by a hospital and its staff to patients and their families and what this means. I am not speaking specifically about a legal duty, breach of which might result in litigation for negligence, but rather a broader ethical duty of care which imports the values of respect, compassion and honesty. To my mind, such a duty arises from the inherent nature of health care itself which is to care for the person, physically and psychologically - to cure where possible, and to provide relief, support and comfort where it is not. 2 The importance of respect for the dignity of the dying person is a principle with which no one would argue. We all appreciate the huge and important advances that have been made in medicine, however we must at the same time ensure that the care of the person does not become overly medicalised to the extent that sight is lost of the fact that the person in the bed is an individual with a voice, wishes and interests, who may have already come to terms with their impending death, and is not simply a patient for whom treatment is being provided by numerous healthcare professionals across multi-disciplinary teams in an attempt to maintain vital functions. Although palliative care has encouraged medicine to be gentler in its acceptance of death, yet medical services sometimes continue to regard death as something to be resisted, postponed or avoided. The challenge for doctors here is to balance technical intervention with a humanistic approach to their dying patients. We need practices and structures that offer a compassionate and competent response to illness, fragility and mortality. We need a patient-centred approach which will focus on the patient’s health, identity and relationships as well as the processes that support the delivery of good care. I would like to draw the Committee’s attention to the National Consent Policy which was published in May of this year by the HSE. The Policy is intended to apply to all health and social care services conducted by or on behalf of the HSE. I was the Chairperson of the National Consent Advisory Group which drafted this policy and I look forward to its effective implementation to ensure a consistent and high quality consent process in all hospitals and service areas across the country. There are a few matters in the policy which I believe are particularly pertinent to the discussions we are currently engaged in. Respect and dignity - Consent is a process whereby a person gives permission for an intervention following communication of information about the proposed intervention. The ethical rationale behind the importance of consent is the need to respect the person’s right to self-determination – that is, their right to control their own life and to decide what happens to their own body. Good healthcare decision-making involves trust between the patient and doctor, open and effective communication and mutual respect. It is important to acknowledge that although those providing healthcare can usually claim greater expertise in decisions regarding the means to achieve the end of better health, such as what medication to use, we must bear in mind that the patient is the expert in deciding what ends matter to him or her, how they want to live their lives, what risks they are prepared to take and so on. 3 Role of the family – The National Consent Policy points out that no person such as a family member, friend or carer, and no organisation, can give or refuse consent to a health or social care service on behalf of an adult patient or service user unless they have specific legal authority to do so. This also means that a family member is not legally entitled to direct that any services be provided or withheld, or more importantly, that any information be withheld from a patient. There is very little understanding of this position amongst families and within the healthcare system. Service providers should aim to have good relationships with patient’s families, particularly to consult with them about what the patient may or may not want for themselves if the patient is unable to communicate those wishes. However, in reality this can be challenging to clinical staff where there is disagreement within the family or where there has been a breakdown of trust between the family and the clinicians. Further support, training and guidelines as well as more public awareness and discussion in this area would assist everyone involved in these potentially difficult situations. Do not attempt resuscitation (DNAR) orders – A DNAR is a written instruction to healthcare staff not to attempt CPR in the event of cardiac failure. It does not have any application to any other aspect of the patient’s treatment and care. Concerns existed in the hospital system about a lack of consistency in how resuscitation decisions were made and a lack of clarity about the decision-making process in this regard. The National Consent Policy provides clarity around the issues pertaining to CPR and DNAR orders only in the context of consent – it does not provide guidance for technical and practical considerations relating to resuscitation procedures. The National Consent Advisory Group was of the view that there is a need for national guidelines on these issues and I submit that this area would also benefit from wider public discussion so that the public is aware of the decision-making process involved here. In 2005 I was appointed by the then Minister for Health, Mary Harney TD, to write a final report on post-mortem practice and organ retention. In my report I highlighted the lifelong nature of bereavement, and the instinct we have when a loved one dies to provide the deceased person with as much dignity as possible even in death. Hospitals must be mindful that they have a duty of care not only to the patient but also a duty which extends after death to show respect for the person’s body and to minimise the distress of families by ensuring that appropriate measures are taken in caring for the body. What the hospital staff 4 see as a body is still someone’s mother, father, spouse or child even after death. In particular, where a post mortem examination is to be carried out, great care must be given to the way in which this is communicated to families and their authorisation sought for this procedure. The family’s experience of the death of their loved one will last for months and years to come, and will affect their quality of life and emotional health in many cases. Although improvements have taken place in this area through the publication of national standards for post-mortem practice in 2012, and work done by the Faculty of Pathology in its quality assurance framework, it is regrettable that the Human Tissue Bill which was recommended in my report in 2005 has yet to be published and enacted. The enactment of this Bill would ensure clarity and consistency of standards in relation to obtaining consent or authorisation for post mortem examinations and organ retention and provide reassurance to the public that the organ retention controversy of the past will never happen again while at the same time encouraging medical education and valuable and ethically approved research. Thank you.