first draft - empiresait

advertisement

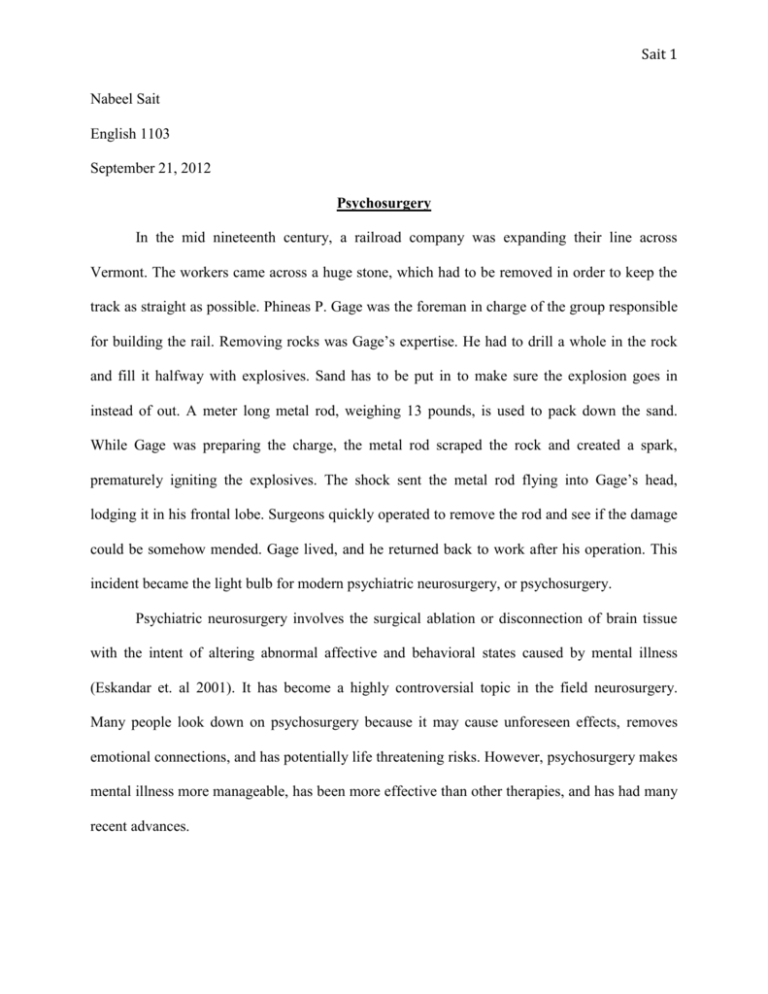

Sait 1 Nabeel Sait English 1103 September 21, 2012 Psychosurgery In the mid nineteenth century, a railroad company was expanding their line across Vermont. The workers came across a huge stone, which had to be removed in order to keep the track as straight as possible. Phineas P. Gage was the foreman in charge of the group responsible for building the rail. Removing rocks was Gage’s expertise. He had to drill a whole in the rock and fill it halfway with explosives. Sand has to be put in to make sure the explosion goes in instead of out. A meter long metal rod, weighing 13 pounds, is used to pack down the sand. While Gage was preparing the charge, the metal rod scraped the rock and created a spark, prematurely igniting the explosives. The shock sent the metal rod flying into Gage’s head, lodging it in his frontal lobe. Surgeons quickly operated to remove the rod and see if the damage could be somehow mended. Gage lived, and he returned back to work after his operation. This incident became the light bulb for modern psychiatric neurosurgery, or psychosurgery. Psychiatric neurosurgery involves the surgical ablation or disconnection of brain tissue with the intent of altering abnormal affective and behavioral states caused by mental illness (Eskandar et. al 2001). It has become a highly controversial topic in the field neurosurgery. Many people look down on psychosurgery because it may cause unforeseen effects, removes emotional connections, and has potentially life threatening risks. However, psychosurgery makes mental illness more manageable, has been more effective than other therapies, and has had many recent advances. Sait 2 The history of psychosurgery predates the start of recorded history itself. The earliest procedures involved open operations with excision of both frontal lobes (frontal lobectomy) or disconnection of the frontal lobes from the remaining brain using a blunt instrument (Eskandar et. al 2001). Numerous reports exist of prehistoric examples of trepanation. Although the therapeutic purpose of trepanation is open to speculation, it likely included the treatment of psychiatric illness. The most well documented example is a skull found in the Neolithic burial site of Ensisheim in Alsace, France, which dates to roughly 5100 BC (Robinson et. al 2012). Since the skull shows signs of healing, the individual was alive well after the operation. Which means it was in fact an operation and not trauma. Trephination is the removal of a circular piece of bone. Literature on trephination for the relief of neuropsychiatric symptoms including affective and psychotic disorders can be dated to 1500 BC. Thus, the history of psychosurgery is as ancient as the recorded history of psychiatric disease itself (Mashour et. al 2005). The birth of modern psychosurgery is attributed to the Swiss psychiatrist Gottlieb Burckhardt. Influenced by the climate of brain–behavior correlation in the latter half of the 19th century, and in particular the demonstration by Mairet of hypertrophic temporal gyri in schizophrenic patients, he performed the first psychosurgical procedures of the modern era in 1888 (Mashour et. al 2005). Burckhardt published a report of his experience in 1891, in which he described three of the procedures as successes, two as partial successes, and one which resulted in the death of the patient. Despite the functionally eloquent location of his lobectomies, he made little mention of any associated postoperative deficits. After his initial report was met with significant disapproval by his peers, Burckhardt did not pursue his experiments any further (Robinson et. al 2012). Sait 3 One reason for controversy in psychosurgery is because the operation may cause unforeseen effects to the patients. An example of this is Henry Gustav Molaison. Molaison was a victim to severe epileptic episodes. He suffered from seizures for many years. The surgeons observed that his hippocampus was atrophic, or “wasting away”. They hypothesized that removing the vestigial region of his hippocampus might solve the problem. After the surgery, Molaison almost never suffered form seizures. His problems were all but cured. However, after the surgery, Molaison could not remember anything for more than a day. Molaison was influential for the discovery of the function of the hippocampus, memory formation. Incidents like this could occur again, that is why many argue that psychosurgery is unethical. It could potentially do more harm than good to the patient. Psychosurgery is used only as a last resort for most cases. However, some patients become too reliant too reliant on the surgery. It makes them unable to help themselves by regular means. Many people who have mental illnesses can usually learn cope with their complications. However, psychosurgery becomes an option only if it is necessary. The surgery changes people. In the case of Phineas Gage, a week after the operation, people started noticing that he wasn’t the same man that knew before. The man everyone thought was intelligent and kind became a violent alcoholic who couldn’t even hold a job. Gage’s friends found him “no longer Gage,” Harlow wrote. The balance between his “intellectual faculties and animal propensities” seemed gone. He could not stick to plans, uttered “the grossest profanity” and showed “little deference for his fellows” (Twomey 2010). The impossible case of Gage is a perfect example of how surgery can affect one’s family. The worst aspect of psychosurgery is the irreversible facet. Once part of the brain is removed, and the damage is done, it cannot be put back. Any postoperative characteristics in the Sait 4 patient become permanent. Even death is a possible postoperative outcome. Families who choose to go with surgery often know the potential consequence of their loved ones. It is an incredibly difficult choice to make. For that reason, many opponents of psychosurgery say that it should not even be an option. Paralysis is fairly common as well. Some people are completely cured of their illness, but become bed-ridden due to paralysis. Even though the potential outcome of the operation may be deterrent for most families, the ones who successfully complete the operation with no complications are relieved. Most operations are completed to succession with no postoperative problems. Psychosurgery makes the mental illness much more manageable for the patient. It gives them a chance to finally return to life and family. It is much harder to cope with violent schizophrenia, but if it is more manageable, someone who couldn’t hold a job could finally support his or her family. Those with violent or aggressive behaviors can be “tamed”. The success rate for psychosurgery has improved a lot since the 19th century. The effectiveness of psychosurgery in alleviating symptoms or in restoring normal functioning was assessed in both studies by standard psychiatric tests, examination of patients, and interviews with close friends or family members. In Mirsky's study, 14 of the 27 patients had very favorable outcomes, were enthusiastic about the surgery, and would undergo the operation again under similar circumstances. The remainder of the patients had results, which ranged from only moderate improvement to worsening of their condition, and their feelings about the surgery were mixed. If the number of those who experienced moderate improvement is added to those who were very much improved, however, the success rate in Mirsky's study would be 21 out of 27 (78%) (The National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research 1977). Sait 5 Psychosurgery has proven to be more effective than psychoactive drugs or electrotherapy. Often both methods, being reversible, don’t permanently solve the patients’ problems. If patients fail to take their medication or not attend their electrotherapy session they might fall victim to their illness. Operation is only used as a last resort, but if the effects are positive, the patients will not have to worry about repeated payment for expensive therapies such as psychoactive drugs or electroshock therapy. The most significant innovation to propel the minimalist vision of psychosurgery was the development of surgical stereotaxis. There was a general feeling that the principles of psychosurgery were sound but that smaller and more specific structures should be targeted to achieve optimal therapeutic benefit while avoiding unnecessary morbidity and unwanted neurologic deficits (Robinson et. al 2012). The stereotactic neurosurgical method uses minimally invasive approach to psychosurgery. Stereotactic surgery enabled a much more circumscribed lesion, resulting in fewer side-effects and less mortality. Furthermore, developments in the neurobiology of emotion provided more refined targets for neurosurgical intervention (Mashour et. al 2005). This means that more patients will have a higher chance of success in comparison to the frontal lobotomy approach. Advances in psychosurgery give patients another chance at life. Patients can see loved ones that they haven’t met in a long. Families can make connections with the patient that couldn’t be formed before because of their illness. It gives hope to those who have lost all faith in seeing their family together again. While the history of psychosurgery may seem grim to most, the future holds a promising outcome for victims of mental illness. Psychosurgery may be unpredictable, it may change the patient, it could be life threatening. However, with research, the future of the operation will make mental illness more manageable, it will be more successful than other therapies, and it will allow Sait 6 patients to go home. More research is definitely required in order to better help people. The development of psychosurgery is linked to the development of all of the clinical neurosciences, as well as the underlying cognitive and basic neurosciences. A multi- disciplinary approach with careful regulation will be essential to the advancement and ethical administration of such therapies for medically refractory psychiatric disease (Mashour et. al 2005). Sait 7 Works Cited: [Anonymous]. 1977. Report and Recommendations: Psychosurgery. The National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. 1- 76 Eskandar EN , Cogrove GR , Raush SL . 2001. PSYCHIATRIC NEUROSURGERY. Functional and Stereotactic neurosurgery [2005 May 11, cited September 20, 2012] http://neurosurgery.mgh.harvard.edu/functional/Psychosurgery2001.htm Mashour GA, Walker EE, Martuza RL. 2005. Psychosurgery: past, present, and future. Brain Research Reviews 48 409–419 Robison RA, Taghva A, Liu CY, Apuzzo ML. 2012. Surgery of the Mind, Mood, and Conscious State: An Idea in Evolution. World Neurosurgery. 662-682 Twomey S . 2010. Phineas Gage: Neuroscience's Most Famous Patient. Smithsonian. [2010 Jan, cited September 21, 2012] http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history- archaeology/Phineas-Gage-Neurosciences-Most-Famous-Patient.html