Annexure – D

advertisement

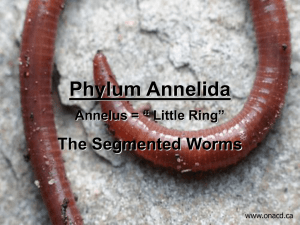

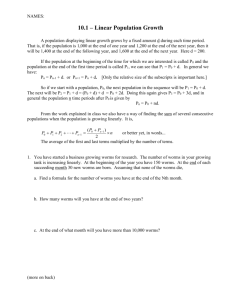

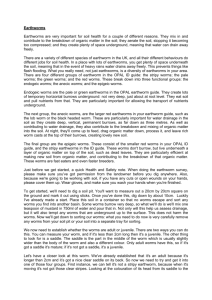

Understanding Earthworms Learn to make fantastic compost with some underground helpers. The pale red garden earthworm is often called "nature's plow." That's because an earthworm pushes through soft earth with the point of its head. If the soil is hard, the worm eats its way through, forming interconnected burrows, some several feet deep. Burrows loosen the soil, admitting air and water and helping roots grow. A single acre of cultivated land may be home to as many as 500,000 earthworms, each making the soil a better place for plants. Earthworms In Your Garden When you add nitrogen-rich compost to your soil, you help worms thrive. However, adding synthetic nitrogen fertilizers may repel earthworms. Worms are very sensitive to physical and chemical changes and will flee the salty conditions that result from an application of chemical fertilizer. As an earthworm feeds, organic matter passes through its body and is excreted as granular dark castings. You may see these small casting piles in your garden. An earthworm produces its weight in castings daily. Worm castings are a wonderful fertilizer, rich in nutrients otherwise unavailable to plants. In cold weather, a soil search will turn up mature and young earthworms as well as eggs. By late spring, most worms are mature. As temperatures rise, activity slows; many lay eggs and then die. By midsummer, most worms are very young or protected by egg capsules. As the weather cools, young worms emerge. With wet weather, they grow active, making new burrows and eating extra food, resulting in more worm castings. Egg laying occurs again. Activity continues as long as soil stays damp. After a heavy rain, earthworms often appear aboveground. They haven't drowned. Fresh water doesn't disturb earthworms—they need ongoing skin moisture to breathe—but stagnant or contaminated water forces them from their burrows. Earthworms can survive in soil that freezes gradually, but sudden freezing can kill them. Protect earthworms against sudden freezes with mulch or a cover crop, both of which also provide worms with food. Earthworm Bins You can raise earthworms yourself using purchased redworms—a process called vermiculture or earthworm composting. Kept in a cool, dark place, such as a basement, a worm bin provides a composting system for kitchen scraps and a source of rich, fertile worm castings for the garden. Commercial Bin Systems Commercially available bins are typically made from durable black plastic, with trays that fit on top of a base. The trays have mesh bottoms for drainage, and the base catches "worm tea" and dispenses it from a spigot so you can use it to water your plants. A top keeps light out and worms from escaping. You fill the lowest tray with a moist filler material (usually a soaked coir fiber brick and/or shredded paper, with a little compost or garden soil mixed in to provide beneficial organisms). The filler should be uniformly damp but not wet, just like any working compost pile. Once you add the worms, you can begin adding kitchen scraps every day or so as the worms consume them, transforming them and the filler into nutrient-rich castings. As with any compost pile, keep meat, fats, and dairy products out of the pile. Coffee grounds and filters, tea bags, oatmeal, bread, and fruit and veggie scraps are excellent worm compostables. As each tray fills with castings, you can repeat the process in the tray above. Worms will migrate through the mesh to the new source of food, and you can then spread the contents of the lower tray on your garden or greenhouse beds or use it to enrich potting soil. Put the newly emptied tray at the top of the bin, and the cycle can go on indefinitely. Another advantage of commercial multi-tray bins is that they're portable, so you can set one up outdoors in a shaded area during the growing season, then move it to the greenhouse, sunroom, or basement when cold weather arrives and continue composting. Homemade Bins Commercial bins work beautifully, but tend to be pricey. If you don't want to pay big bucks for a worm bin, you can make your own from a plastic storage bin, such as a 3 feet by 2 feet by 1 1/2-feet-deep storage bin, a modified garbage can, washtub, or wooden box. Use an awl to punch small holes in the sides of plastic washtubs or garbage cans for aeration. To keep conditions moist but well drained, make a drainage area in the bottom of the bin; use a rigid divider to separate it from the worms' living quarters. A loose cover keeps flies and light out and worms and moisture in. Just as with commercial bins, it's best to fill the bin with soaked coir and newspaper. (You can buy compressed coir bricks from garden supply stores, catalogs, and Web sites, and from sources of worm-composting supplies.) Garden soil may also be added. Make sure the mix is as damp as a wrung-out sponge rather than wet. Then introduce the purchased earthworms to their new home. Use your purchased worms for composting only—most commercially available worms are species that live only in manure or very rich soil and will not survive in average garden soil. One exception is the enriched soil in a greenhouse bed—if the greenhouse stays above freezing, worms will do very well there. Feed your worms well-chopped vegetable matter mixed with a bit of water. Soft foods are best for the first few days; if food doesn't disappear in 24 hours, reduce the amount. For faster composting, run the food through a blender, since worms don't have teeth to tear off large chunks. The population should double in about a month; after 60 days, your bin should be full of rich compost. To harvest the compost, but save your earthworms for another session, place the compost outdoors on a sheet of heavy plastic or fabric, and let it sit for about an hour. The worms will cluster together to stay cool and moist. Dig in and find the cluster. Return the worms to the bin or start a second bin.