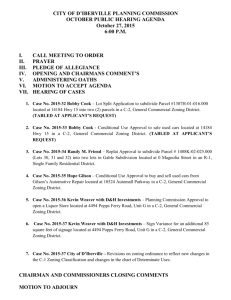

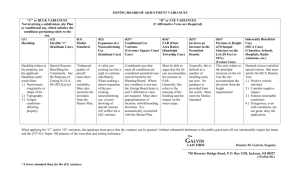

The Relevance and Admissibility of Rezoning and

advertisement