DOCX file of Youth Transitions Evidence Base: 2012

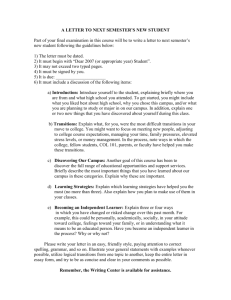

advertisement