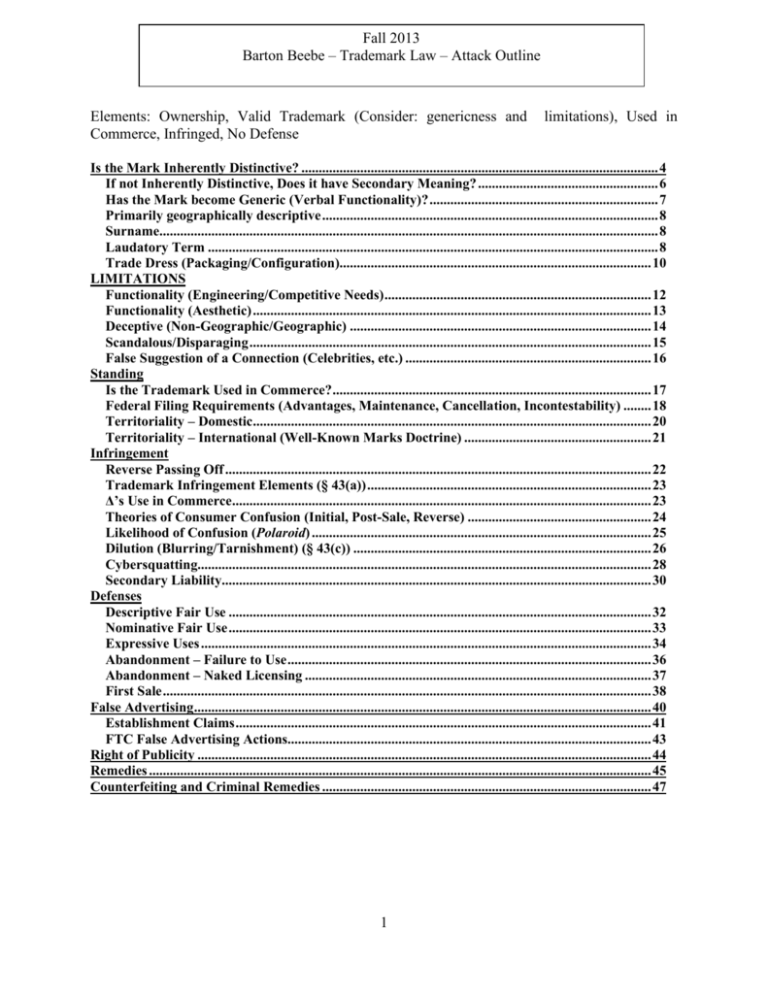

Fall 2013 - NYU School of Law

advertisement