Clinical Synopsis A 32year old female presented with a four year

advertisement

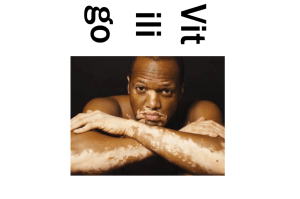

Clinical Synopsis A 32year old female presented with a four year history of depigmented patches on the face trunk and extremities. These depigmented patches were irregular, well demarcated and nonpruritic. Both lips were affected sparing the hands and the feet. Six months prior to presenting to our clinic, a small nodule appeared in a depigmented patch on the left leg. The nodule rapidly increased in size and became ulcerated. At the time of presentation the tumor measured 4cm in diameter (Fig. 1). Thorough examination of the left limb did not reveal any other growths. The inguinal lymph nodes were not enlarged. She had no personal or family history of melanoma. Fig. 1: Lateral (A) and aerial (B) view of a tumor arising from the centre of a vitiligo patch. The Brown coloration is due to povidone iodine An excision was done with a 1cm safety margin and deeper to subcutaneous tissue. The histological examination the tumor was composed of nested atypical melanocyte (Fig. 2). The tumor cells expressed S-100, Melan-A (Fig. 3) and HMB-45. The proliferation activity was high (MIB-1) with many mitotic figures. At six months follow up there was complete healing without recurrence and no changes in the inguinal nodes. The patient was later lost to follow up. Fig. 2: H & E showing nested atypical melanocytes Fig. 3: Tumor cells stained positive with Melan-A Discussion The prevalence of vitiligo in the general population is estimated at 1%1 while the prevalence of vitiligo in patients with malignant melanoma has been reported to range from 3%-6%2,3. There are different depigmentary changes associated with melanoma; ranging from halo nevus, achromic patches on melanoma scars, depigmentation of injection site of immunotherapy and depigmentation associated with regressing malignant melanoma. The association of vitiligo with regressing melanoma has been widely reported in literature, however primary melanoma presenting initially with vitiligo is very rare. Lugo-Somolinus et al4 reported two cases of vitiligo-like primary melanoma. We report a case of primary melanoma arising in vitiliginous lesion. The pathologic mechanism of vitiligo is not clearly known. Complex factors involving cellular and humoral immunity, toxic metabolites and genetic factors partly contribute to its pathogenesis. Ciuet al5 demonstrated that antibodies to melanocytes were present in both vitiligo and melanoma patients which were directed to similar melanocyte antigens. The implicated antigens are tyrosinase, melan A, gp100 and TRP-26. This association explains the simultaneous appearance of vitiligo and regressing melanoma but contradicts the occurrence of melanoma in vitiligo lesions. Tobin et al7 observed that melanocytes are never completely cleared from vitiligo lesions and that this melanocyte can recover their functionality. Similary, Gottschalk et al8 reported melanocyte survival in three cases of vitiligo which had been inactive for 2-5years. Melanoma may develop from these melanocytes that have escaped immune destruction. The mechanisms of immune escape are not clearly known but Le Poole et al9 hypothesized that the tumor escape may be due to early activation of T-cells secreting IFN-α which contribute to tumor escape and development of vitiligo. Vitiligo-like lesions are generally regarded as a good prognostic factor in melanoma patients10,11. The survival rate of these patients has been shown to be better than would have been expected for a patient with a similar melanoma stage. This may be attributed to destruction of melanocyte by an enhanced immune response In conclusion, we present a patient with a rapidly growing amelanotic melanoma arising from vitiligo lesions without evidence of tumor elsewhere. The six months follow up period might be short to assess the recurrence. Reference 1. Kovacs S. Vitiligo. J Am AcadDermatol.1998;38:647-66. 2. Wang JR, Yu KJ, Juan WH and Yang CH. Metastatic malignant melanoma associated with vitiligo-like depigmentation. Clin Exp Dermatol.34, 209–211 3. Berd D, Mastrangelo MJ, Lattime E, et al. Melanoma and vitiligo: immunology’s Grecian urn. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1996;42: 263–267. 4. Lugo-Somolinos A,Sa´nchez JL, and Garcia ME. Vitiligo-like Primary Melanoma. Am J Dermatopathol 2008;30:451–454 5. Cui J, and Bystryn J. Melanoma and Vitiligo Are Associated With Antibody Responses to Similar Antigens on Pigment Cells.Arch Dermatol. 1995;131(3):314-318. 6. Merimsky O, Shoenfeld Y, Baharav E. Melanoma-associated hypopigmentation: where are the antibodies? Am J Clin Oncol. 1996;19: 613–618. 7. Tobin DJ, Swanson NN, Pittelkow MR et al. Melanocytes are not absent in lesional skin of long duration vitiligo. J Pathol 2000; 191: 407–16. 8. Gottschalk GM, Kidson SH. Molecular analysis of vitiligo lesions reveals sporadic melanocyte survival. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:268–272. 9. Le Poole C, Wan˜kowicz-Kalin˜ska A, Van den Wijngaard R, et al. Autoimmune aspects of depigmentation in vitiligo. J Invest Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:68–72. 10. Duhra P and Ilchyshyn A. Prolonged survival in metastatic malignant melanomaassociated with vitiligo.Clin Exp Dermatol.1991; 16: 303-305. 11. Arpaia N, Cassano N, Vena GA. Regressing cutaneous melanoma and vitiligo-like depigmentation. Int J Dermatol 2006; 45: 952-956