Mark Wilson Opening of the Caribbean Branch of the US Cochrane

advertisement

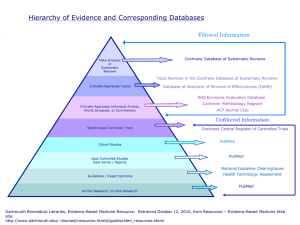

Mark Wilson Opening of the Caribbean Branch of the US Cochrane Centre 6th June 2013 First, let me say what a pleasure and a privilege it is to be with you on this very special day. I was asked to speak about how we got here – the history of the Cochrane Collaboration, its evolution and impact on health practices – and where we are going – our future direction, the new opportunities and challenges we face. 1. How did we get here? As the programme brochure explains, The Cochrane Collaboration is named after Archie Cochrane, a British doctor and epidemiologist who was active in medical practice and research from the 1930s to his death in the late 1980s. He is best known for his influential book, Effectiveness and Efficiency: Random Reflections on Health Services. In it he suggested that because health resources would always be limited, they should be used to provide those forms of healthcare which have been shown - in properly designed evaluations - to be effective. In particular, he stressed the importance of using evidence from randomized controlled trials (commonly known as RCTs) because these were likely to provide much more reliable information than other sources of evidence. “It is surely a great criticism of our profession,” he subsequently wrote, “that we have not organized a critical summary, by specialty or subspecialty, adapted periodically, of all relevant randomized controlled trials.” Effectiveness and Efficiency was originally published in 1972, but over forty years later it is still fresh and engaging and I’m delighted to announce that this year The Cochrane Collaboration will be digitally republishing the book with a new Foreword by our Co-Chairs, Jeremy Grimshaw and Jonathan Craig. It is – in many respects - our founding charter, a call to arms that was read by doctors all over the world and which planted the seeds in the minds of a few who, over time, began talking about how to respond to the challenge effectively. Of course, pre-eminent amongst that new generation was Iain – now Sir Iain – Chalmers: a brilliant doctor, impassioned writer and quite astonishing force of nature! Some of you know Iain Chalmers far better than I do, and he gathered a small group of like-minded clinicians, 1 researchers, academics and policy makers together to form The Cochrane Collaboration in the early 1990s to take up Archie Cochrane’s challenge and embed evidence-based medicine in policy and practice. The critical importance of undertaking this work is encapsulated in The Cochrane Collaboration’s logo. The inner part of the logo illustrates a systematic review of data from seven RCTs, comparing one healthcare treatment with a placebo. This diagram shows the results of an early Cochrane Review, examining RCTs of a short, inexpensive course of a corticosteroid given to women about to give birth too early. The first of these RCTs was reported in 1972. Over the following 20 years, a number of additional studies were conducted examining the same treatment. Over time the evidence indicated, through systematic review, that treatment of pregnant women with corticosteroids reduces the odds of their babies dying from the complications of prematurity by 30 to 50 per cent. But until a systematic review of these trials was published, most obstetricians were unaware that the treatment was so effective, and it was not widely used. As a result, it is likely that tens of thousands of premature babies suffered and died unnecessarily (and needed more expensive treatment than was necessary). This example is one of many illustrating the human costs resulting from failure to perform systematic, up-to-date reviews of RCTs of health care – and the powerful impact of evidence on guidelines, on practice, and on mortality rates. It is the driving force behind The Cochrane Collaboration’s vision: “…that healthcare decision-making throughout the world will be informed by high-quality, timely research evidence. We will play a pivotal role in the production and dissemination of this evidence across all areas of health care.” Today, more than 20 years after the initiative inspired by Archie Cochrane and bearing his name, The Cochrane Collaboration is an established international organization with more than 28,000 volunteers working in 120 countries. There are now 53 subject-based Cochrane Review Groups, 16 specialised Methods Groups and 12 thematic Fields and Networks. Their work is supported by 500 people employed on behalf of the organization around the world and in the Collaboration’s central offices in Oxford and London. The Collaboration has now published more than 5,300 reviews and 2,300 protocols in The Cochrane Library, along with 700,000 records in the Cochrane CENTRAL Register of Controlled Trials. Last year, nearly five and a half million full text downloads of Cochrane Systematic Reviews from The Cochrane Library were made; and usage of the Library went up by 25% on that in 2011. The 2 Collaboration’s growth, development, outputs and contribution to modern medicine over the last 20 years is truly astonishing – something we can be immensely proud of. But the path to where the Collaboration is now has often been an uphill climb, and there have been substantial obstacles along the way. From the very beginning, the founders of The Cochrane Collaboration encountered philosophical opposition from members of the medical community, many of whom were challenged or affronted by the idea of evidence-based medicine – that amassing and examining evidence could legitimately undermine beliefs and practices they had learned in medical school and utilized in their professional careers. The founders of The Cochrane Collaboration were generally considered upstarts, mavericks and renegades in the wider healthcare community, dedicated to an esoteric idea and prone to cultish behavior. This, inevitably, had financial repercussions, particularly in the early days of the Collaboration. Funders of health services and research institutions either didn’t know about the concept of systematic compilation and assessment of evidence, or didn’t understand its potential impact on practice. Research institutions did not consider conducting systematic reviews - which consisted mainly of evaluating other people’s primary research - to be legitimate research in itself, worthy of financial support or of academic attention. This made funding difficult to obtain at the organizational level, and for individual Cochrane contributors. Healthcare professionals, particularly those working in academic disciplines, often found the response to their Cochrane involvement discouraging for the same reasons. At best, preparing systematic reviews was not considered to be as valuable as primary research; at worst, it was viewed as poaching other people’s work; and across the board it was unlikely to be considered a legitimate use of academic research time or a stepping-stone to academic achievement. Then, as now, the Collaboration’s greatest asset in overcoming obstacles in its path was the determination, dedication, and enthusiasm of its contributors. In the early days, when members of the funding, academic, and healthcare communities were unaware of or unconvinced by the arguments in favor of an evidence-based approach, Cochrane collaborators across the organization made two critical contributions: First, they contributed their time and efforts, generally working for little or no money, to help increase the critical mass of systematically reviewed Cochrane evidence; 3 Second, they worked to raise awareness in their own organizations - to make people aware of why systematically reviewed evidence was important and, if they succeeded in convincing them, making them aware of how and where to find it and use it. As a result, attitudes and practices have changed over time, as evidenced by two telling examples: the first involves The Lancet, one of the UK’s most prestigious medical journals. In the early days of the evidence-based medicine movement, The Lancet published an editorial hostile to the very concept. By 1995, it had hailed The Cochrane Collaboration as “an enterprise that rivals the Human Genome Project in its potential implications for modern medicine”, and in 2005 it announced that authors submitting manuscripts reporting clinical trials would henceforward be required to include a clear summary of previous research findings, ideally by direct reference to a systematic review. The second example involves the Impact Factor. This measurement, as most of you will know, assesses the frequency of citations of academic journals and is calculated annually by the Institute for Scientific Information. It is widely recognized in the research community as a standard for ranking and comparing journals, and is considered as part of grant evaluation and research assessment processes. In the earliest days of The Cochrane Collaboration, when the value of systematic reviews had not yet been widely recognized, The Cochrane Library was not evaluated as part of the ISI’s Impact Factor assessment. As The Cochrane Library’s scope and reputation increased, so did its level of citations, and in June 2008 the ISI recognized its importance by granting the Library an Impact Factor ranking. This now stands at 5.9; and The Cochrane Library is the tenth-most cited medical journal in the world. The Cochrane Collaboration’s impact on health practice has been gradual but pervasive. From being an abstract and unfamiliar concept, ‘evidence’ has become a way of thinking for people involved in healthcare at every level. The Collaboration’s principles of promoting access and enabling wide participation have made evidence-based healthcare an approachable and applicable concept for patients and clinicians, journalists and researchers, policy makers and funders. One of the Collaboration’s principal goals is to make Cochrane evidence available to end users via oneclick access. In 2003, 10 years after the Collaboration’s foundation, we signed our first publishing agreement with John Wiley & Sons. This agreement moved the Collaboration’s publishing platform from its original location – a small, Oxford-based digital publisher that had been instrumental to the early growth of the Collaboration’s technical infrastructure and publishing output – to a major international company with a worldwide reputation for excellence in digital and scientific publishing. This relationship 4 has given the Collaboration unprecedented opportunity to make Cochrane evidence available and accessible to a global audience. Now, in more than 100 countries worldwide, access to The Cochrane Library is provided without charge, making Cochrane evidence freely available to every citizen of those countries. Throughout the Caribbean and Latin America, access is freely available via the Virtual Health Library, thanks to funding provided by BIREME, the Pan American Health Organization and the World Health Organization. And in some 20 other countries worldwide, including Australia, India, and the United Kingdom, nationwide access to Cochrane evidence is provided by government funding. Providing access is only one facet of The Cochrane Collaboration’s partnership with the World Health Organization. This partnership, established in 2011, allows the Collaboration to promote evidence-based health care at the highest levels of international policy-making, and includes a seat on the World Health Assembly. Formalizing this partnership gives us the opportunity to expand our collaboration with WHO, which is already well established through initiatives such as the Reproductive Health Library. This resource has helped millions of women and babies in low- and middle-income countries through practice recommendations on newborn health, pregnancy and childbirth, and sexually transmitted infections. Another area in which Cochrane evidence has had a significant impact is in informing the development and implementation of national guidelines for practice. In the United Kingdom, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (also known as NICE), which develops guidelines for clinical practice throughout the National Health Service, works to ensure that Cochrane evidence underpins guidance wherever possible. Since 2008, NICE has published nearly 100 guidelines in which 500 Cochrane Reviews are cited: with 73% of the guidelines citing at least one Cochrane Review (and one of them cites 46!). This is a clear demonstration of the impact of Cochrane evidence on healthcare practice and the return on investment in Cochrane research made by the UK’s Department of Health since the Collaboration’s earliest days. 2. Where are we going? I have been speaking about our past and our present – what about the future? This year, even as The Cochrane Collaboration celebrates its 20th anniversary, we are turning our focus on some substantial challenges, both inside the organization and in the industries and communities with which we work, as we establish our new Strategy to 2020, which I hope we will finalise at the Collaboration’s annual Colloquium in Quebec, Canada, in September. 5 The two main motifs of the new strategy are already clear: Firstly, An External Focus: we need as an organization to be much more oriented to the users of our Systematic Reviews and evidence-based products and services. Secondly, after Archie Cochrane’s book title, Become more Effective and Efficient Internally: Whilst keeping the dynamism and creativity that has made the Collaboration what it is, we need to become more supportive, effective and efficient in the way that we work and create and deliver those products and services. I have highlighted the astonishingly effective ways in which the Cochrane has impacted on the world. This must be our future main driver – the beginning and end of all of our thinking. We must adopt an ‘outside-in’ approach which starts with the needs of the global audience of end-users of Cochrane evidence and the uses to which they put our work. We want Cochrane Reviews to be the first choice for answering any healthcare-related question. In working towards this goal, we will seek to produce reviews that are always relevant, timely and of high quality. How does that change how we produce, deliver and present synthesized evidence? Are we answering the questions these end users are asking, at the right time and in the right way? Are we giving clinicians, researchers, patients, carers and health policy makers the information they need it and in a form which is most useful to them? As large as we have grown, and as enthusiastic as our contributor base is, our resources are not unlimited, and as we continue to grow we must grapple with balancing the need for maintaining our broad coverage of healthcare areas with identifying and addressing priorities for particular user groups: whether their needs are determined by geographical setting, resource restrictions, acute situations, or any of the host of other considerations that drive healthcare research, policymaking and practice. The information revolution has brought a transformation in the way research information can be made available to end users. The growth of Open Access across scientific and medical publishing presents a considerable challenge to traditional publishing frameworks, with the costs moved from readers and users of information and intellectual property to those who produce it. This is a challenge the Collaboration has already begun to address. Working with our long-term publisher, John Wiley, with whom we signed a new publishing contract earlier this year, we have introduced a two-tier model aimed at increasing open access to Cochrane evidence. This framework represents an important development for the Collaboration, but it is only a first step towards what is likely to be a substantially different publishing model. 6 This move towards an Open Access model also has significant financial implications for the Collaboration. Revenues from The Library have grown enormously over the last decade and this growth has fostered investment in the Collaboration’s infrastructure aimed at supporting the work of Cochrane contributors worldwide. I’ve just flown down from New York where we have been working on how we can develop The Cochrane Library in the coming years and new derivative products and services which will sustain the organization in the future whilst meeting our goal to make Cochrane Systematic Reviews freely available for the whole world. How the Collaboration produces synthesized evidence more efficiently and effectively is the second main motif of the new strategy. We must, for example, get better at making the experience of writing and producing a Cochrane Systematic Review easier, faster and more enjoyable. By doing so we will retain and build expertise and capacity, and ultimately improve the quality of our outputs. We will be looking at every stage of our production process, at our organizational structure, at how we coordinate and communicate with each other, and how we continue to ensure that ‘Cochrane’ remains the watchword for high-quality systematic reviews. We will be helped by new technological opportunities. The Collaboration was a pioneer in the use of electronic publishing technology and we are already at the leading edge of using ‘Linked Data’ technology to present content in innovative ways, tailoring it to the needs of a growing number of audiences. We will invest in the technology that is central to this approach and embrace new tools, processes, and interfaces to facilitate the completion of reviews, mitigate workloads for Cochrane contributors, and maximize the usability of Cochrane evidence. In facing these challenges, we must not lose sight of the fact that the quality and applicability of Cochrane evidence remains paramount. Recent events have highlighted the ongoing issue of unreported trial data, and the growing awareness worldwide that data from thousands of clinical trials remain unavailable to researchers, clinicians, and the public. Without complete information from trial results, information is lost, bad treatment decisions may be made, opportunities for better and more effective treatment are missed, and trials are repeated unnecessarily, duplicating effort and wasting resources. Cochrane Reviews cannot hope to provide a comprehensive picture of the evidence available if 50% of trial data, as is often estimated, remains unreported. To raise awareness and promote action on this issue, the AllTrials initiative was formed earlier this year. The Cochrane Collaboration is a principal supporter and organizer of the initiative, marshaling the collective strength of our worldwide representation to bring international attention to this issue. 7 The Cochrane Collaboration will also become a truly global organization. Today is part of that process, and I am thrilled that this new Caribbean branch will become a bridgehead for the promotion of evidence-based healthcare in the region and as a way to expand our profile and impact in the lives of the millions of people who need and deserve the most effective healthcare that improves their lives. Not only will Cochrane break out of its traditional geographic areas of strength, but we will be investing in much greater translation initiatives that will make Cochrane evidence available to many more people around the world. There are currently 14 Cochrane Centres, and, with the opening of this Caribbean Branch, 18 Branches. Cochrane Centres coordinate, support, and promote Cochrane activity at a regional level. They act as a main point of contact and information for a particular geographical or linguistic area; provide training and support to Cochrane contributors and entities working in their area; and act as a liaison between Cochrane and the local healthcare community. Cochrane Centres work to raise the profile of the Collaboration to everyone involved in health care in their own region, from patients to clinicians to researchers to policymakers, fostering a two-way dialogue that works to bring Cochrane evidence to the healthcare community, and users and seekers of evidence into the ongoing work of the Collaboration. Branches have a particularly important role to play in this organizational infrastructure. Most of the Cochrane Centres are responsible for coordinating Cochrane activity across large and diverse areas, and the specialized local knowledge that Branches can contribute is critical to building relationships and identifying the specific information and support needs of a particular area. I hope that in the coming years the new Caribbean branch will have a profound impact on regional health care by: Disseminating Cochrane evidence and information across the region; Improving practice and outcomes; Building capacity to continue the work of generating and assessing evidence; and Bringing this expanded Caribbean healthcare community into active membership within Cochrane’s global network so that we can learn from each other. I hope I have met my brief; and given you an insight on where The Cochrane Collaboration has come from and where it is going. I am tremendously excited by the prospect that the new Caribbean branch will be joining us on that journey. Our programme has on its cover a photograph of the statue which is 8 on this University of West Indies campus, of the Savacou bird-god who controlled thunder and strong winds. I was amazed to read that Archie Cochrane donated this statue and that a wonderful link has already been established between us. But I am sure that Professor Cochrane would have approved when I say that I hope that the vibrant work of this new Cochrane branch will become the most important, farreaching and influential Cochrane legacy in the university, in Jamaica, and across the region. I look forward to working closely together with Damian, Marshall and all of your colleagues - and I look forward to Savacou’s strong winds blowing The Cochrane Caribbean’s newest branch and the organization as a whole to great future success. Thank you! 9