Chesapeake Bay TMDL Survives Legal Challenge

Written By Brian G. Glass for The Legal Intelligencer*

In a cooperative federalism model, federal and state governments work together to

achieve a common goal. The Clean Water Act employs this model to accomplish many of its

objectives, including that of restoring the nation’s polluted waters. Commentators have observed

that cooperative federalism can be “messy.” Perhaps no one knows that better these days than

Judge Sylvia H. Rambo, who spent the better part of a year wading through the mire in an

industry challenge to the Chesapeake Bay Total Maximum Daily Load for Nitrogen,

Phosphorous, and Sediment (Chesapeake Bay TMDL), promulgated on December 29, 2010, by

the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Last month, Judge Rambo emerged from the

swamp and issued a long awaited decision in the case. When the mud had settled, the

Chesapeake Bay TMDL was still standing.

In Am. Farm Bureau Fed’n, et al. v. EPA, et al., Civil No. 1:11-CV-0067 (M.D. Pa.),

several agricultural interests and others filed a complaint seeking a declaratory judgment and

asking the court to vacate the Chesapeake Bay TMDL. A TMDL is a key component in the

cooperative federalism framework that the Clean Water Act employs to restore impaired waters.

Under that framework, states first establish, subject to EPA review, water quality standards,

including the criteria that they deem necessary to protect various water uses. Next, states

identify waters that fail to meet those standards and record them on lists (commonly referred to

as 303(d) lists), which they submit to EPA every two years for approval. Finally, for each of the

impaired waters on the 303(d) lists, states must establish total maximum daily loads, or TMDLs.

A TMDL is the total maximum daily load of a pollutant that is presently impairing a water body

that the water body can assimilate from all sources of pollution within the watershed and still

meet water quality standards. Just as a doctor might prescribe a target weight to improve the

health of an overweight patient, states establish a target pollutant load to restore the ecological

health of a water body that has been impaired by that pollutant.

In its regulations, EPA defines a TMDL as the sum of the maximum amount of a

pollutant that a body of water can receive from point sources (waste load allocations, or WLAs),

non-point sources (load allocations, or LAs) and natural background. As this equation suggests,

there are two ways that a state can reduce pollutant loads to a waterbody to meet the limit in a

TMDL: it can reduce WLAs by ratcheting down effluent limitations in permits issued to point

sources regulated through the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit

program, and/or it can reduce LAs by, for example, directing available federal funding to

projects within the watershed designed to decrease pollution from nonpoint sources not regulated

through the NPDES permit program. How a state decides to reduce pollutant load will inform

how a state budgets a TMDL among WLAs and LAs (e.g., a state that wants to avoid imposing

stringent limits on point source dischargers will assign more of the TMDL to WLAs than to LAs,

thereby requiring significant reductions from nonpoint sources). As with water quality standards

and 303(d) lists, states submit TMDLs to EPA for review. Before EPA approves a TMDL, it

conducts what is known as a “reasonable assurance” analysis to ensure that the TMDL does not

contain overly generous assumptions regarding the amount of nonpoint source pollution

reduction that will occur.

The Chesapeake Bay is the largest estuary in the United States, draining a 64,000-squaremile watershed covering large sections of six states (Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania, New

York, Delaware, and West Virginia) and the District of Columbia (collectively, the Bay States).

Although the Chesapeake Bay has been described as “one of the most biologically productive

ecosystems in the world,” changes in land use over time have impaired its ecological health. A

number of sources located throughout the watershed, including agricultural operations, urban and

suburban stormwater runoff, and wastewater facilities, have been contributing excess nitrogen,

phosphorous and sediment to the Bay. These pollutants have caused algae blooms that deplete

the oxygen that fish and shellfish need to survive and that obstruct the sunlight that sustains

important underwater vegetation, resulting in dead zones unable to support aquatic life. After

more than 30 years of agreements, amendments, schedules, goals, programs, and strategies, all of

which have proven unsuccessful in restoring the water quality of the Chesapeake Bay, the Bay

States and EPA agreed that EPA would establish a Chesapeake Bay TMDL with a target date of

2025 for when all pollution control measures necessary to meet applicable water quality

standards must be in place.

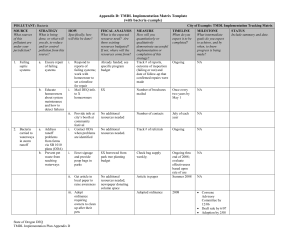

EPA and the Bay States developed target loads for nitrogen, phosphorous and sediment,

which the Bay States used to develop draft watershed implementation plans. These roadmaps for

achieving target loads consisted of schedules for accomplishing reductions and identified

programs and actions to achieve those reductions. EPA conducted a “reasonable assurance”

analysis on these draft plans following their submission. Where EPA found “reasonable

assurance” lacking, it made adjustments, which were referred to as “backstop” allocations. EPA

then used the draft plans and backstop allocations to develop a draft Chesapeake Bay TMDL,

which it published for a 45-day public comment period. During that time, EPA continued to

work with the Bay States to strengthen their plans, effectively reducing to three the number of

backstop allocations EPA used to develop the final Chesapeake Bay TMDL. The largest and

most complex TMDL ever promulgated, the Chesapeake Bay TMDL established allocations of

185.9 million pounds per year of nitrogen (a 25 percent reduction from current levels), 12.5

million pounds per year of phosphorous (a 24 percent reduction), and 6.45 billion pounds per

year of sediment (a 20 percent reduction) among the Bay States.

The gravamen of plaintiffs’ complaint in the Am. Farm Bureau Fed’n case was that the

Chesapeake Bay TMDL was an unlawful federal implementation plan that impeded on states’

rights. In her decision on cross-motions for summary judgment, Judge Rambo agreed with

plaintiffs that TMDL implementation primarily rests with the states and that the Clean Water Act

does not authorize EPA to establish or otherwise take over TMDL implementation in the same

way that it allows EPA to issue its own water quality standards, 303(d) lists, or TMDLs in the

absence of state submissions or when it finds state submissions to be inadequate. Nevertheless,

Judge Rambo rejected that states have exclusive authority over the implementation of TMDL

allocations or that the Chesapeake Bay TMDL represents an unlawful implementation plan.

Plaintiffs advanced several arguments in support of their claim that EPA unlawfully

intruded on the Bay States’ implementation authority. After finding that plaintiffs possessed the

requisite standing to pursue their claims despite failing to submit supporting evidence in their

opening brief, Judge Rambo systematically shot down all of these arguments, as summarized

below.

Definition of TMDL. Although EPA’s regulatory definition of TMDL as the sum of

WLAs and LAs (plus natural background) has been in effect for more than 25 years and has been

used to develop more than 25,000 TMDLs, the plaintiffs in this case were the first to challenge it,

arguing that the Clean Water Act only authorizes EPA to establish a total maximum daily load

(i.e., one number). Applying traditional Chevron analysis, the court found that in defining a

concept as complex and technical as a TMDL, the Clean Water Act left plenty of room for

interpretation and that EPA’s regulatory definition was reasonable and entitled to deference.

Detailed Allocations. Plaintiffs argued that EPA unlawfully micromanaged TMDL

implementation by allocating pollutant loads among various sectors and by establishing WLAs

for individual permitted facilities. The court found that assigning allocations during TMDL

development, when agencies are working together in a coordinated fashion to evaluate the health

of an entire water body, is reasonable, and that delegating such allocations to individual permit

writers would be unworkable, particularly in a watershed extending across political boundaries.

The court also rejected the contention that EPA was solely responsible for the allocations in the

TMDL, finding that the process of developing the TMDL was more representative of cooperative

federalism than unlawful coercion, notwithstanding a handful of documents in the record that

plaintiffs cited to argue the contrary.

Reasonable assurance and backstop allocations. Plaintiffs argued that EPA’s

“reasonable assurance” requirement represented an unlawful attempt by the agency to insert

itself into TMDL implementation, but the court found that reasonable assurance was little more

than a standard upon which EPA evaluated proposed allocations. Plaintiffs argued that the three

backstop allocations imposed by EPA where it found reasonable assurance lacking unlawfully

overrode state decisions on TMDL implementation, but the court found ample support for EPA’s

backstop authority in several provisions of the Clean Water Act.

Insufficient flexibility. Plaintiffs argued that the TMDL created unlawfully binding

allocations “by locking [detailed] allocations in, establishing a federal timeline for

implementation, and reserving exclusive authority to revise them.” The court disagreed. While

EPA regulations require that NPDES permits contain effluent limitations for point sources that

are “consistent with the assumptions and requirements of any available [WLA in a TMDL],” the

court observed (as did the TMDL itself) that EPA regulations do not require that effluent

limitations be identical to the WLAs in a TMDL. States are also able to submit proposed

modifications to EPA for approval, and the TMDL contains a number of provisions offering

additional flexibility, like those supporting water quality trading programs. The court rejected

plaintiffs’ argument that the federal grant program coerces state action, finding that states remain

free to choose both if and how to implement the TMDL. Finally, the court noted that the 2025

implementation target established by the TMDL was the result of a consensus reached by EPA

and the Bay States and not a unilateral directive from EPA.

Watershed approach. Plaintiffs argued that EPA only has the authority to issue

allocations to tidal states and not to upstream, headwater states. The court found that while

nothing in the Clean Water Act expressly authorizes EPA to take a holistic, watershed approach

to TMDL development, nothing in the Act prohibits such an approach either, and the court found

the approach to be consistent with the Act and otherwise supported by EPA regulations. In

endorsing the approach, the court was persuaded by Supreme Court precedent sustaining EPA’s

authority to regulate upstream pollution sources in order to achieve downstream water quality

standards.

After concluding that EPA did not exceed its authority under the Clean Water Act, the

court turned to plaintiffs’ other claims. The court first rejected plaintiffs’ argument that EPA’s

45-day public comment period was unreasonable, finding that it exceeded the statutory

minimum, that the TMDL drafting process had effectively been ongoing for more than a decade,

and that plaintiffs were unable to demonstrate prejudice. This inability to demonstrate prejudice

was also fatal to plaintiffs’ claims that they were deprived of key modeling information during

the public comment period, as the court declined to be guided by a footnote in a Third Circuit

opinion suggesting that a regulated party automatically suffers prejudice when members of the

public are denied access to the complete public record. Finally, the court found a rational

relationship between allegedly flawed models and data that EPA used to develop the TMDL and

the reality that those models and data sought to represent. As such, the court rejected that their

use was arbitrary and capricious.

Assuming the decision in the Am. Farm Bureau Fed’n case survives any appeal that may

be filed, the approach that EPA took in developing the Chesapeake Bay TMDL is likely to

become a national model that the agency employs to restore other impaired waters that overlap

state boundaries, particularly where nonpoint sources are the prevailing sources of the

impairment. That this approach can withstand legal challenge has now been established. As for

whether it can succeed in restoring impaired waters like the Chesapeake Bay? On that matter

the jury is still out.

BRIAN G. GLASS is a partner at Warren Glass LLP, an environmental and water resources law

practice. He draws on more than a decade of varied environmental law experience to help his

clients design solutions to environmental problems that achieve multiple business objectives.

He can be reached at bglass@warrenglasslaw.com.

Reprinted with permission from the October 11, 2013 edition of The Legal Intelligencer©2013

ALM Media Properties, LLC. All rights reserved. Further duplication without permission is

prohibited. For information, contact 877-257-3382, reprints@alm.com or visit

www.almreprints.com.