Aesthetics on the secondary market

advertisement

Aesthetics on the secondary market

Bruno Blondé (University of Antwerp - Centre for Urban History), Britt Denis (University of

Antwerp - Centre for Urban History) and Jon Stobart (University of Northampton)

Introduction

For decades the history of material culture and consumption has been caught in ‘grand

narratives’. Historiography has long passed the initial enthusiasm of McKendrick cum suis,

authors selling eighteenth-century consumer changes as ingredients of the ‘birth of a

consumer society’. This does not prevent other generalising master narratives from playing a

major role in recent material culture and history of consumption research. The “industrious

revolution” concept is undoubtedly one of the most influential, though not uncontested,

intellectual frameworks that currently prevail. While authors such as Jan de Vries excel in a

refined and balanced intellectual analysis of eighteenth-century consumer changes, by and

large it is overarching arguments and concepts (such as luxury, novelty and comfort) that lead

their thoughts (de Vries, 2008). When it comes to the ‘material’ of ‘material culture’, several

scholars have already argued in favour of a fundamental shift from an intrinsic value-based

expenditure and ownership pattern to a designbased consumer model. This, again, is a general

model that – even accounting for its typological

explanatory potential rather than its actual historical

character – tends to frame material culture changes

into one, overarching general process and

discourse. In doing so, as Maxine Berg

acknowledges, the most influential historiography

shares a major common feature: it pays little

attention to the specific objects studied (Berg 2005,

85): ‘While so much of the recent history of

consumption in the eighteenth century has focused

on the role of demand and on new consumer

aspirations, it gives little consideration to consumer goods themselves’. Moreover, while the

historiography has developed a hegemonic narrative centred around ‘fashion’,

‘industriousness’, ‘comfort’, ‘luxury’ and ‘pleasure’, too little is still known about the way

cultural values were actually constructed and bundles of characteristics woven around specific

objects and groups of objects.

The main aim of this contribution consists to analyse the subtle discursive ways in which

objects obtained value in eighteenth-century newspaper advertisements. Rather than focusing

on advertisements for ‘new shops’ and ‘new objects’, we deal in this article with

announcements of auctions, more particularly the general auctions in which all kinds of

1

household goods were offered for sale. By focusing on this type of advertisement we hope to

put different material objects into a comparative perspective. Indeed, not only household

furniture, but also textiles, silverware, clocks, kettles, chinaware and coaches were offered for

sale and advertised well in advance through notices in the local and metropolitan newspapers.

Hence, auction announcements offer the unique possibility of looking at a more complete

context in which objects were offered for sale. In principle, probate inventories could serve a

similar purpose, but they are not rich in documenting product qualities (Overton 2004, 114116) and, for obvious reasons, appraisers were not inclined to use persuasive adjectives –

persuasion being not the ultimate goal of drawing up an inventory. As with inventories, of

course, wealthier householders are over-represented in newspaper ads as they were more

likely to have their estate auction announced, whether post mortem, after bankruptcy or

relocation. As a result, our analysis tends to focus upon material culture patterns among these

wealthier households.

For this paper, the bulk of the qualitative data are drawn from the Gazette van Antwerpen, a

sample being taken for the years 1730-1731, 1759-1761 and 1789-1791. This generated a total

of 3676 advertisements. To this, we have added a much smaller set of advertisements from the

Daily Advertiser (a London newspaper, sampled for 1772) and Adams Weekly Courant (from

Chester, sampled 1778-79), together with a range of examples taken from the broader

provincial press in eighteenth-century England. This material can be subjected to multiple

interrogations, but we focus here on the ways in which material objects were described. What

kinds of adjectives were used and to what extent did these vary between different types of

objects? Can we discern an over-arching discourse centred around ‘novelty’ or ‘fashion’ or

were other priorities more important? By drawing data from two countries, our analysis has an

important comparative dimension and allows us to consider the ways in which the

local/national cultural and economic milieu impacted on the description of material objects

being offered for sale. Moreover, comparing these descriptions to the language deployed in

the printed catalogues for auctions of household goods also allows us to place newspapers

into a comparative framework.

A language of persuasion?

It has been argued elsewhere that eighteenth-century advertisements employed a rhetoric of

persuasion, although this was often couched in terms of politeness both in linguistic and

cultural terms (Lyna and Van Damme 2009; Stobart 2008). Advertisements for the sale of

household goods generally followed a standard format. They began with an announcement of

when and where the auction would occur; then headlined the type and sometimes the

character of goods being offered for sale, before offering a more detailed list of the particular

objects available. At the bottom of the advertisement were details of arrangements for

viewing the lots and sometimes information about where auction catalogues could be

obtained.

2

The Antwerp data reveal that the majority of goods were advertised without recourse to any

adjectival modifier whatsoever (Table 1). For England, the picture is more impressionistic,

but it appears that this ‘silence’ was far less common: only a quarter of auction advertisements

were without qualitative descriptions, although a further 40 percent described the goods as

‘genuine’, rather than in truly qualitative terms. The relative absence of adjectives to describe

the qualities of auctioned goods as a whole does not exclude persuasion, however. Very often

this was derived from the mere juxtaposition of different objects: the ‘chairs, sofas, pierglasses, girondoles, dining, Pembroke and card tables, India dressing glasses and boxes,

carpets … four post and tent bed-steads with damask, chints, morine, cotton, Manchester and

other furniture, fine down and goose-feather beds, blankets quilts, counterpanes, matrasses …

Kitchen articles, brewing vessels &c’ advertised by Joseph Skerrett (Adams Weekly Courant,

17 March 1778) forms both an inventory of comfortable living and evokes a sense of variety

and consumer choice that were critical attributes in the eighteenth century (Coquery 2011,

273-274). Very often, moreover, auctioneers stressed this variety and abundance of choice in

an overt way. On Friday, January 16th 1789, for instance, an auction was announced in the

Gazette van Antwerpen in which a large set of furniture (“een groote partije grove meubelen”)

with – among other things – different chests were offered for sale next to, again among others,

a large set of paintings (Gazette van Antwerpen, 16 January 1789). On February 6th a long list

of goods was auctioned on the Antwerp Friday Market. The preceding advertisement did a

good job of evoking the splendour and variety of the goods that were offered for sale, yet the

description was concluded by a meaningful and more other goods too many to be mentioned

(“en meer andere goederen te lang om melden”) (Gazette van Antwerpen, 2 February 1789).

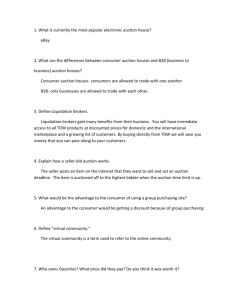

Table 1. Descriptions of auction lots in eighteenth-century Antwerp auction advertisements

(A)

(B)

(C)

N

%

% (only auction

descriptions)

Other

218

5,930359 35,44715

Schoon (beautiful)

306

8,324266 49,7561

Curieus ('curious')

11

0,299238 1,788618

Kostelijk (precious)

12

0,326442 1,95122

Mode (fashionable)

4

0,108814 0,650407

Modern

40

1,088139 6,504065

New

7

0,190424 1,138211

lots

with

3

Kunstig (ingenious)

4

0,108814 0,650407

Uitmuntend

(excellent/outstanding)

13

0,353645 2,113821

No quality given

3061

83,26986

Total

3676

100

100

When we zoom in on the Antwerp auction lots that were accompanied by modifiers (column

C), a very diverse picture appears. Indeed, a considerable proportion of auction lots were

described with the help of ‘unique’ adjectives or descriptors, such as the large set of perfumes

and exquisite pomades that were announced for sale on May 30th 1789 (Gazette van

Antwerpen, 29 May 1789). However, when this large residual ‘other’ category is removed, by

far the most frequently used descriptor referred to the aesthetic quality of object groups,

usually in terms of the description ‘schoon’ (79 percent), followed by the presupposed

‘modernity’ of the goods (8 percent). Schoon can be translated as beautiful, but it has far more

nuanced meanings, including handsome, fine, clean and pure. The fine detail of nuances that

come with the use of adjectives related to aesthetics have yet to be explored in detail.

Moreover, it goes without saying that auction advertisements fall short in contextualising

“beautifulness” in a detailed way.

The same variety of meanings comes out more explicitly in the English advertisements, with

both the beauty and cleanness of the auction goods being emphasised. The former is brought

out through adjectives such as ‘elegant’ and ‘neat’, both of which were redolent with

significance for eighteenth-century householders. As Vickery argues, these terms ‘embodied

the social distinctions of provincial gentility’: they communicated ideas of good taste rather

than ostentatious grandeur, but lifted both goods and their owners above mere respectability

(Vickery 1998, 161; 2009, 180-2). Newspaper advertisements thus pitched the auctioned

goods as signifiers of gentility – an association reinforced by auction catalogues which added

‘genteel’ to the descriptions (MacArthur and Stobart 2010, 184) . In describing goods as

‘genuine’, auctioneers were saying something about their provenance, but they were also

reassuring potential purchasers about the reputable nature of the objects being offered for sale.

One advertisement noted that the listed objects were ‘all perfectly clean goods’ (which echoes

the ‘schoon’ of Antwerp advertisements), while another elaborated further. Under a headline

emphasising the goods as elegant and a long list of objects being sold, the auctioneer

concluded his advertisement with the promise that: ‘There are no Scraps or Scrapings of

Time, to be met with in this House – most of the Articles are new – Beauty and Art are so

happily blended in the principal Pieces, that, it is hoped, Criticism will lose her Sting on the

Day of Viewing and give an assenting Nod on the Day of Sale’ (Daily Advertiser, 30 January

1771; Northampton Mercury, 3 January 1780).

At the same time, of course, these were used goods, one of the key attractions of which was

their price relative to those purchased new. It is striking, therefore, that the newspaper

4

advertisements in Antwerp and England make no mention of goods being cheap – a selling

point increasingly emphasised in advertisements for new goods, from tea to textiles, and a key

part of the rhetoric of persuasion deployed by shopkeepers (Stobart, 2008, Lyna and Van

Damme, 2009). What is seen in a small proportion of English, but intriguingly not in Antwerp

advertisements, is an emphasis on the auctioned goods being ‘valuable’. Contra de Vries’

arguments, this reflects the continued importance of material objects as stores of wealth and

perhaps links to gentry and middling sort concerns for ‘prudent economy’ in terms of securing

good quality goods at much reduced prices (Harvey 2012, 64-98; Vickery 1998, 127-60;

Nenadic 1994a, 1994b)

Objects of desire?

As well as qualitative descriptors being attached to the auctioned goods as a whole, some

advertisements also promoted individual objects or groups of objects in this way. Overall this

practice followed a very similar pattern to that described above (Table 2). By and large,

Antwerp advertisements provided detailed lists of goods, but auctioneers seldom were

inclined to make use of adjectives to heighten their attraction to potential purchasers. This was

undoubtedly linked to the need to restrict the length of the advertisement, partly because they

were priced according to the space they occupied and partly to avoid them becoming too long

for readers to bother with. However, there is also some tantalising evidence that auctioneers

were wary of being seen to ‘puff’ the goods. In an auction catalogue, one Northamptonshire

auctioneer acidly observed: ‘Bombast Puffing of Pictures as well as other Articles, is always

ridiculous; as not furnishing any just or clear Ideas by which the unskilled may form any

judgment of their Merits, but at the same time never fails to excite the Laughter and Contempt

of the Connisseur [sic.]’ (Catalogue for auction at Islip Mills, 19 December 1787). That only a

small proportion of objects were given a qualitative descriptor is thus unsurprising; but neither

is it a huge setback for our analysis. Indeed, such selectivity adds enormously to the marginal

value of those objects that were effectively described with greater precision (column C).

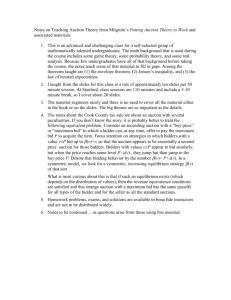

Table 2. Quality descriptions of objects in eighteenth-century Antwerp auction advertisements

(A)

(B)

(C)

N

%

% (only objects with descriptions)

Other

41

0,376147 3,510274

Schoon (beautiful)

927

8,504587 79,36644

Curieus (curious)

6

0,055046 0,513699

Kostelijk (precious)

5

0,045872 0,428082

5

Mode (fashionable)

9

0,082569 0,770548

Modern

97

0,889908 8,304795

New

53

0,486239 4,537671

Old

15

0,137615 1,284247

Kunstig (ingenious)

0

0

Uitmuntend

(excellent/outstanding)

15

0,137615 1,284247

No quality given

9732

89,2844

Total

10900

100%

0

100%

Again, it is not so much the novelty of objects, or their capability to evoke modernity, but

rather the beauty of things that was marketed. Indeed, ‘schoon’ becomes predominant in the

Antwerp adverts, accounting for nearly 80 percent of the occurrences of descriptive modifiers

(Table 2). Much the same was true in England, where elegant, neat, fine and handsome were

predominant. This underlines our earlier argument that these used goods were being linked

firmly into ideas of gentility and taste. They reflected the ways in which the (lesser) gentry

viewed and described themselves as ‘civil’, ‘genteel’, ‘well-bred’ and ‘polished’ (Vickery,

1998, 13). Whether such groups were the most prominent amongst the buyers at auctions, and

indeed whether the goods actually merited these descriptions, is less important than the social

and cultural world in which they were being situated. These objects were ‘declared’ as

beautiful, elegant and genteel (a word used far more often in auction catalogues than

advertisements) and were thus rendered markers of this status . (Stobart 2011, 95-96; Searle

1975) It is possible, of course, that this language of aesthetics may have been the vector

hiding characteristics such as ‘novelty’ and ‘fashionability’ or even economy and value. But it

is telling that reference was made to the aesthetics of things rather than to the characteristics

most often applauded in the historiography of eighteenth-century consumption.

Figure 1. Percentage of auction lots with a quality indication

6

45

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

Not all objects were equally likely to be described in detail. The Antwerp data shows quite

clearly that paintings were accorded qualitative descriptors far more often than were other

categories of goods (Figure 1). More importantly, despite the predominance of aesthetic

descriptions, different types of goods were described in rather different ways, suggesting that

the nature of the object was significant in how it was viewed and portrayed as an object of

desire. In this context, the combination of adjective and noun was important, influencing the

meaning of both, according to the particular context. A handsome painting, for example,

meant something rather different from a handsome dining table or a handsome coach.

Furthermore, different categories of goods were characterised by a variety of secondary

descriptions.

Unsurprisingly perhaps, paintings were predominantly described in terms of their aesthetic

appeal: they were things of beauty and portrayed as such in the auction advertisements

(Figure 3). In England paintings were mostly sold framed and these were occasionally

described in detail, again with their aesthetic qualities to the fore. While auction catalogues in

the Netherlands provide similar details, ads were shorter in describing works of art, with a

strong emphasis on the aesthetics of paintings. Yet aesthetics were not the only selling point

for paintings; their value was also emphasised. In English advertisementsreference was

sometimes made to specific painters or genres – no doubt as a way of heightening their appeal

to the cognoscenti. For example, when advertising a sale in Gresford near Chester, the

auctioneer noted ‘A large Collection of Paintings, by the best Masters, A very large

Collection of original Drawings, many of which are scarce and valuable, and fine

Impressions’ (Adams Weekly Courant, 19 January 1779). In Antwerp as well the value of

paintings was often constructed by emphasising the fame of the painters such as the very

beautiful of a painting by Snijders representing an orderly “camp-veldt” (“een extra schoone

schilderye, representerende een ordentelyck camp-veldt, zynde geschildert door den grooten

fameusen konst schilder Snayers”) that was offered on August 18th 1760 (Gazette van

Antwerpen, 12 August 1760).

7

Figure 2. Quality descriptions of auction shares (lots) by object category

400

300

200

100

0

Other

Schoon (beautiful)

Curieus (curious)

Kostelijk (precious)

Mode (fashionable)

Modern

New

Kunstig (ingenious)

Uitmuntend (outstanding/excellent)

No quality given

Figure 3. Quality descriptions of auction shares (lots) by object category in % (objects without

description excluded)

100%

80%

60%

40%

20%

0%

Other

Schoon (beautiful)

Curieus (curious)

Kostelijk (precious)

Mode (fashionable)

Modern

New

Kunstig (ingenious)

Uitmuntend (outstanding/excellent)

More surprising is the fact that textiles and clothing, the usual hunting ground for the tyranny

of fashion, were not the most common objects to be described in such terms. ‘Modern’

formed a small minority of descriptions used for textiles in the Antwerp data (Figure 3) and

8

‘fashionable’ appeared on a few occasions in English advertisements. Rather, it was

silverware, the ‘old luxury’ par excellence, that was mostly circumscribed as modern or

fashionable, though modernity also migrated to furniture and fashionability to coaches and

carriages that entered secondary markets. Thus we see the inclusion of ‘several lots of modern

plate’ in the metropolitan sale of Mr Serjeant Leigh’s possessions and of ‘upwards of two

Hundred Ounces of fashionable Plate’ in an auction in Nantwich (Daily Advertiser, 23 June

1772; Adams Weekly Courant, 17 March 1778). Intriguing as it seems, the crediting of an ‘old

luxury’ with ‘modernity’ and ‘fashionability’ is less contradictory. Increasingly indeed, the

added value of silverware played a large role in discriminating between owners with and

owners without taste (Blondé 2009). Silverware, for obvious reasons, appealed to centuriesold patterns of conspicuous consumption, but thanks to its high intrinsic value and its

potential for melting and remaking, it also borrowed from the feverish and volatile eighteenthcentury culture (Baatsen and Blondé 2011). Broadly similar arguments might be made for

coaches, the pars pro toto of an elite lifestyle. Here, the elegance of the vehicle and quality of

manufacture were both emphasised, but so too was the fact that they were ‘little used’ or ‘very

little the worse for wear’ (Northampton Mercury, 6 June 1743; Berrow’s Worcester Journal,

24 September 1772). Aesthetic qualities were thus combined with practical considerations,

but also with notions of modernity, coaches also being described as modern built – a phrase

which suggests stylistic considerations as well as mere age. In Antwerp, readers were

informed of a beautiful, new and modern carriage that was furbished with mock-velvet of

three different colours (Gazette van Antwerpen, 8 February 1791). As key positional goods,

therefore, fashion and modernity mattered when buying a coach second-hand as much as it

did when the vehicle was new.

The age of an object could also important when taken in the opposite direction. While auction

goods overall were never described as old, this term was sometimes attached to furniture and

especially porcelain. This was more evident in England than Antwerp and may reflect the

earlier development of a taste for antiques, which was sufficiently prevalent by the early

nineteenth century to support a substantial cluster of specialist shops in Soho. Even then,

however, auctions remained an important source for such goods (Wainwright, 1984; Stobart,

2011). In Antwerp, advertisements sometimes labelled porcelain and also textiles as ‘curious’,

a description which might allude to their attraction to collectors. English advertisements were

more specific. There was ‘rare old’ china; a ‘set of magnificent old Japan Jars and Beakers’,

and ‘Cabinets, Chests and Screens of the rare old Japan’ (Daily Advertiser, 14 March 1772;

Daily Advertiser, 7 February 1772). These allusions to scarcity underlined the attraction and

potential value of the objects both in cultural and economic terms. Such old and rare items

might form additions to collections which, as McCracken argues, reflected the taste,

knowledge and wealth of the owner (McCracken 1990, 45-50).

Even with these object groups, however, it was aesthetic qualities that predominated.

Descriptions of furniture could be especially rich, with elegant, handsome, neat or fine being

used alongside the materials from which the pieces were made. Thus we read about neat

Mahogany furniture, fine feather beds and beautiful rosewood cabinets. Indeed, the combined

aesthetics and materials of particular pieces could prompt lengthy descriptions, one London

9

advertisement waxing lyrical about a ‘most matchless Ladies India Commode of Rose Wood,

richly inlaid with Ivory of curious Workmanship’ (Daily Advertiser, 14 March 1772). Used in

this way, language reinforced some of the key characteristics of such luxury goods: the

quality of materials, intricacy of design, complexity of manufacture and, above all, aesthetic

appeal.

Conclusions

This exploration thus leads to several provisory conclusions. Contrary to the claims forwarded

by Lyna and Van Damme, it is hard to distinguish between the informative and persuasive

nature of auction advertisements. While consumer and material culture historiography tends

to stress general, homogenising concepts such as fashion, industriousness, etc. in the context

of the eighteenth century a very nuanced and multi-layered set of values was woven around

objects that were often defined by very object-specific markers. Overall, however, it was

aesthetics that dominated the discourse on the secondary markets. The emphasis on aesthetic

qualities was firmly rooted in a centuries-old renaissance canon that favoured not only the

intrinsic qualities but especially the decorative potential, design, taste and added value of

luxuries. Though the aesthetic canon in itself obviously changed rapidly with changing

fashion, it was not fashion or novelty per sé that appealed to eighteenth-century customers. In

this way, the emphasis on beauty which requires a judgment of taste, hence knowledge,

helped to reproduce social inequalities in the eighteenth century. Indeed, even though the

transition to new luxuries implied a greater affordability of semi-luxuries by ever greater parts

of the population, in the end it was taste, a savoir-vivre, that discriminated between the real

“haves” and the “have nots”.

10

Bibliography

Baatsen, Inneke, and Bruno Blondé. 2011. "Zilver in Antwerpen: drie eeuwen particulier

zilverbezit in context." In Zilver in Antwerpen: de handel, het ambacht en de klant,

edited by Leo De Ren, 95-125. Leuven: Peeters.

Berg, Maxine. 2005. Luxury and pleasure in eighteenth-century Britain. Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

Blondé, Bruno. 2009. "Conflicting Consumption Models? The Symbolic Meaning of

Possessions and Consumption amongst the Antwerp Nobility at the End of the

Eighteenth Century." In Fashioning Old and New. Changing Consumer Preferences in

Europe (Seventeenth-Nineteenth Centuries). edited by Bruno Blondé, 61-79.

Turnhout: Brepols.

Coquery, Natacha. 2011. Tenir boutique à Paris au XVIIIe siècle. Luxe et demi-luxe. Paris:

Editions du comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques.

Harvey, Karen. 2012. The Little Republic. Masculinity and Domestic Authority in EighteenthCentury Britain. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lyna, Dries, and Ilja Van Damme. 2009. "A strategy of seduction? The role of commercial

advertisements in the eighteenth-century retailing business of Antwerp." Business

History no. 51 (1):100-121.

MacArthur, Rosie, and Jon Stobart. 2010. "Going for a song? Country house sales in

Georgian England." In Modernity and the Second-hand trade, edited by Jon Stobart

and Ilja Van Damme, 175-195. Palgrave.

McCracken, G. 1990. Culture and Consumption. New Approaches to the Symbolic Character

of Consumer Goods and Activities. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Nenadic, S. 1994a. "Household possessions and the modernising city: Scotland, ca. 1720 to

1840." In Material culture: consumption, life-style, standard of living, 1500-1900.

(Proceedings Eleventh International Economic History Congress. Milan, September

1994), edited by Anton Schuurman and L.S. Walsh, 147-159. Milaan.

———. 1994b. "Middle-rank consumers and domestic culture in Edinburgh and Glasgow

1720-1840." Past and Present no. 145:122-156.

Overton, M. 2004. Production and Consumption in English Households, 1600-1750. London:

Routledge.

Searle, John. 1975. "A taxonomy of illocutionary acts Language, Mind and Knowledge." In

Language, Mind and Knowledge, edited by K. Gunderson. Minneapolis.

Stobart, Jon. 2008. "Selling (through) politeness: advertising provincial shops in eighteenthcentury England." Cultural and Social History no. 5 (2):309-328.

———. 2011. "The language of luxury goods: consumption and the English country house,

c.1760-1830." Virtus no. 18:89-104.

Vickery, Amanda. 1998. Gentleman’s Daughter. Women’s Lives in Georgian England. New

Haven: Yale University Press.

———. 2009. Behind closed doors. At home in Georgian England. New Haven; London:

Yale University Press.

11