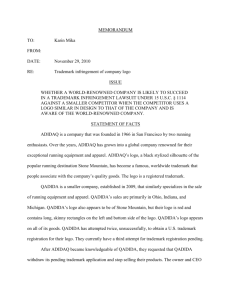

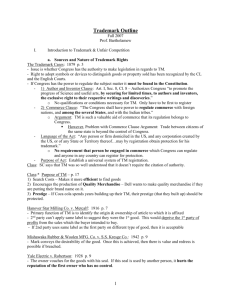

The Supreme Court`s Decision in B&B Hardware, Inc. v. Hargis

advertisement

The Supreme Court’s Decision in B&B Hardware, Inc. v. Hargis Industries, Inc. and Its Impact on Trademark Strategy Questions On March 24, 2015, the Supreme Court rendered its decision in the case of B&B Hardware, Inc. v. Hargis Industries, Inc., Docket No. 13-353, which presented the basic issue of whether a finding of likelihood of confusion by the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (Board) in an opposition proceeding precludes litigating the same issue in a subsequent infringement action between the same parties. I. BACKGROUND The case was on appeal from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit which held that a Board decision was not entitled to any preclusive effect principally on the ground that the likelihood of confusion factors applied in that Circuit and by the Board1 are not the same. B&B Hardware, Inc. v. Hargis Industries, Inc., 716 F.3d 1020 (8th Cir. 2013). Specifically, the Eighth Circuit held that even though some of the respective likelihood of confusion factors are the same or comparable, issue preclusion does not apply unless the Board examined the “entire marketplace context” as is done in an infringement action. The Eighth Circuit concluded that the Board’s consideration of the marketplace context was inadequate because the Board predicated its finding of likelihood of confusion basically on the strong similarity of the marks SEALTITE and SEALTIGHT and ignored the pricing, marketing and product end-use differences between the products. The majority opinion by Justice Alito held that if the other ordinary elements of issue preclusion are met, the Board’s finding with respect to likelihood of confusion should be given preclusive effect in a subsequent infringement action so long as the usages of the marks adjudicated by Board and the District Court are materially the same. In reaching that conclusion, the opinion relied on its determination that likelihood of confusion is essentially the same issue regardless of whether it is decided in a Board proceeding or in an infringement action. II. ISSUE PRECLUSION: WHEN APPLICABLE The key question with respect to issue preclusion will be the nature of the record and uses of the respective conflicting marks in the opposition proceeding before the Board. If the rights relied upon by the party-plaintiff and the substance of the partydefendant’s challenged application in the Board proceeding are essentially the same as that presented in the infringement action, issue preclusion will be applicable. The opinion, relying on the amicus curiae submitted by the Department of Justice, noted that in many contested proceedings “the Board typically analyzes the marks, goods, and The relevant likelihood of confusion factors in question are set forth in SquirtCo v. Seven-Up Co., 628 F.2d 1086 (8th Cir. 1980), and In re E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Co., 476 F.2d 1367 (CCPA 1973). 1 1 channels of trade only as set forth in the application and in the opposer’s registration, regardless of whether the actual usage of the marks by either party differs.” (Slip Opinion, p. 17). Thus, if the Board does not consider the marketplace usage of the parties’ marks, the Board’s decision should “have no later preclusive effect in a suit where the actual usage in the marketplace is the paramount issue.” (Id., p. 18) The same point is set forth in the concurring opinion of Justice Ginsburg that issue preclusion will not apply where the Board only considered the marks “in the abstract and apart from their marketplace usage.” The Supreme Court’s decision should require the District Court in an infringement action to make a careful analysis of the nature of any prior opposition proceeding between the parties in which the Board rendered a decision with respect to likelihood of confusion. The parties in the infringement action should be prepared to address this issue and provide the District Court with an appropriate explanation of the nature of the opposition and the issues presented and the record considered in that proceeding. III. OPPOSITION PROCEEDINGS AFTER B&B HARDWARE The decision will also very likely have a serious impact on how oppositions are handled going forward because the Board’s decision on the issue of likelihood of confusion may be essentially determinative of a subsequent infringement action. Thus, both parties to the opposition are likely to prosecute and defend their respective positions more strenuously, including presenting more extensive evidence than is currently offered and a greater number of requests for oral argument before the Board. The likely result would be a more extensive record and a resulting increased cost in prosecuting and defending an opposition. If the Board does make a finding that confusion is likely, the party-defendant will be faced with the prospect of filing a de novo appeal under § 21(b) of the Federal Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1071(b), which would permit the introduction of new evidence directed to the likelihood of confusion issue resolved by the Board. But if such an appeal were filed, there is a risk that the prevailing party before the Board would file a counterclaim for infringement so that both the right to register and the right to use the mark in issue would be presented. Thus, a § 21(b) de novo appeal would involve significantly increased costs to both parties. IV. OPPOSITION vs. INFRINGEMENT LITIGATION Another possible impact of the Supreme Court’s decision is that the trademark owner may well reconsider the advisability of initiating an opposition proceeding rather than filing an infringement action assuming that the application in issue is use-based. Although such an infringement action would be more expensive and poses the risk of counterclaims that could not be asserted in an opposition, the issue of likelihood of confusion would be resolved based on the evidence introduced in the infringement action and could not be limited to what is covered by the application and the pleaded 2 registrations in an opposition proceeding. If the trademark owner decides to file an infringement action rather than an opposition, the prosecution of the defendant’s application should be suspended pending the disposition of the civil action. Moreover, if there is a finding of infringement and a resulting injunction, that action could be reported to the USPTO in the form of a Letter of Protest showing that the applicant no longer has the right to use the mark in question and thus is not entitled to obtain a federal registration. Exercising the infringement option could seriously lessen the volume of contested proceedings filed before the Board. 3