class notes globalization

Globalization : An introduction

Contents

3.1 A first episode in the XIX th

century ......................................................................................... 11

List of tables

List of figures

1

1. What is globalization?

A set of inter-related factors including, inter alia : i.

A rapid increse of the share of activities open to international competititon ii.

Internationalization of companies in the form of FDI and participations iii.

Increased mobility of production factors (labor and capital) iv.

Convergence of cultural and political values

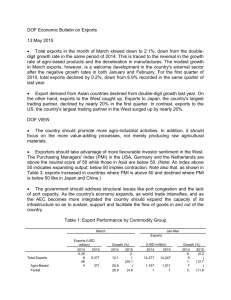

1.1 Openness to international trade at the country level

The increase in goods trade is the easiest to measure since trade flows are recorded by customs administrations in practically all countries.

Figure 1: Trade vs. GDP growth

Trade in goods: (Import + export)/GDP Growth of world trade vs. growth of world GDP

70.00

60.00

50.00

40.00

30.00

20.00

10.00

-

Low & middle income

High income

Source : WDI Source: WTO, World Trade Report 2013

Note the displacement of domestic activity by international competition (creation and destruction of jobs); the increased dependence toward the outside, but by the same token, reduced dependence to internal shocks; the trend reversal at the end of the 80s : emerging countries become more open than industrial ones; and the decline of industrial countries in world activity and trade (better distribution):

2

90.00

80.00

70.00

60.00

50.00

40.00

30.00

20.00

10.00

-

Figure 2: Share of OECD countries in world GDP

(a) In constant dollars (b) at PPP

70.00

60.00

Share of world GDP, constant dollars,

OECD

Share of world GDP, constant dollars, non-OECD

50.00

40.00

30.00

20.00

10.00

-

Share of world GDP at PPP, OECD

Share of world GDP, at PPP, non-OECD

Source : World Bank, World Development Indicators

Figure 3: Evolution of geographical composition of world trade

Source : Yoshino (2012)

Figure 4: 2012 of the largest exporters of goods in the world

3

This trend reversal puts an end to the “great divergence” that started in the XIXth century (Figure

Figure 5: First divergence

Source : WTO, World Trade Report 2013

4

Similar trends can be observed in terms of service trade (Figure 6). Their increase has levelled off

in the end of the 2000s for developing countries but it is probably a temporary blip. The importance of India’s service trade exports is particularly spectacular.

Figure 6: Service exports since the 1970s

(a) Service exports as a percent of gDP, by income level

(b) Same thing, India only

14

12

10

8

6

4

2

0

Low & middle income

High income

8

6

4

2

0

18

16

14

12

10

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators

Figure 7: Exports of commercial services, 2012

Trade in services (% of

GDP)

5

Source : WTO, World Trade Report 2013

1.2 Internationalization of companies

The internationalization of companies can be seen in the growth of FDI flows. (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Net inward FDI flows, percent of GDP

6.00

5.00

4.00

3.00

2.00

1.00

Low & middle income

High income

-

Source : World Bank, World Development Indicators

Note the much smaller order of magnitude (1%-5% of GDP) than for trade. Note also that FDI is very cyclical, particularly so for industrial countries. Finally, flows into Southern and Northern countries are positively correlated : No apparent substitution effect.

Figure 9: Outward FDI flows, percent of GDP

7.00

6.00

5.00

4.00

3.00

2.00

1.00

Low & middle income

High income

-

Source : World Bank, World Development Indicators

As for outward flows, those coming from emerging countries have grown very rapidly (albeit from a very low base). Until the 2000s (roughly) outward flows from developing countries were essentially panics dues to a deteriorating domestic situation. More recently, one can observe a movement of internationalization of Southern companies, like Kenyan supermarkets opening stores in Uganda, Chilean companies expanding into Argentina, and so on), reflecting their increasing power and ambition.

6

2 Global value chains and trade in value added

2.1 The domestic and foreign content of exports

One classical problem of international trade statistics is that exports are not net of intermediate consumption which can be imported, which leads to massive double counting. For instance, if the

U.S. exports compressors to Mexico for assembly into refrigerators to be re-exported to Colombia, international trade stats will count, in Mexico’s exports, the value of the compressors embodied in that of refrigerators. This means that the compressors will have been counted twice (once as U.S.

exports, once as “embodied” Mexican exports) (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Décomposition of gross exports

Absorbed domestically

Foreign VA

As final good

Exported

Domestic VA

As intermediate

For local absorption

To third countries

For export

Multiple counting in trade stats

For re-export back home

How can the black box of exports be opened up ? The procedure needed to generate trade in value added statistics is complex. The first step is to start by detailing the uses of exports, direct and

indirect, by combining an input-output matrix with international trade data (Table 1).

Uses

Sources

Table 1: Input-output matrix with detailed use of exports

Domestic absorption Exports

Sector 1 Sector 2

Dom. final demand

Foreign intermediate use

Foreign final demand For local For export to absorption third countries

For export back to home

Sector 1

Sector 2

Domestic VA

Intermediate imports

Figure 11: Domestic and foreign content of exports

7

Source : Koopman et al. (2011)

One would expect the domestic content of exports to go up with income level, as rich (industrial) countries have a “denser” industrial fabric and so can produce more intermediates at home rather

than importing them. However it’s the opposite (Figure 12): poorer countries have a higher

domestic content. This is likely to be a composition effect across goods: poorer countries export less technologically sophisticated goods which have less foreign content (extreme case of domestic content: agricultural products).

Figure 12: Domestic content of exports and income level

Source : Johnson Nogueira (2010)

An extreme case of the double counting is illustrated in Figure 13 with the ipod’s value chain.

China’s gross export value per ipd is over $200 apiece, yet it contributes only a tiny fraction of all the value added.

8

Human capital,

R&D

150

100

50

0

350

300

250

200

Capital

Figure 13: The value chain of an iPod

Labor

Re-captured by Apple

Japan

US

Korea

China

Source : Adapted from Dedrick et al. 2008

2.2 Measurement and policy implications

How to come up with an estimate of the domestic value added embodied in gross exports?

Conceptually, the problem is as shown in

Uses

Table 2: Domestic value added embodied in gross exports

Domestic absorption

Exports

Sector 1 Sector 2

Dom. final demand

Sources

Sector 1

Sector 2

Domestic VA

Intermediate imports

Let x be country i

’s gross output, i y ij

the final demand in country j for goods from country i , and a ij the absorption of country i ’s output as intermediates in the production of country j . The uses of country i

’s gross output, with two countries i

1, 2 , can be decomposed by the following equation:

a

11 a

12 x a a x

21 22 2

1

y

11

y

12 y

21

y

22 x x

1

2

(1)

9

where a ij is how much of country i

’s gross output is sold as an intermediate to country j (domestic absorption for a ii

, export for a ij

). The equation can be inverted to get « inverse Leontieff matrices » (how much production needed per unit of final demand). Let y

1

y

11

y

12 y

21

y

22

be the total final-demand vector (domestic and exported). Let

B

b

11 b b

21 b

12

22

1

a

11

a

21

a

12

1

a

22

1 be the inverse Leontieff matrix.

1

Gross output can be expressed as a function of final demand as follows: x

1

b

11 b

12 y b

21 b

22

(2)

Finally, let u

T be an N -dimensional vector of ones, N being the number of countries; here N =

2. Let v j

be the share of value added in gross output in country j ; that is, v j

.

i a ij

(3)

We use our inverse Leontieff matrix to construct v v b

1 11 v b

1 12

v b v b

2 21 2 22

. (4)

The share of value added in gross exports (what we are interested in) can finally be expressed by multiplying each element in (4) by the ratio of gross output to gross export, e i

: v

ˆ e v b

1 1 11 e v b

2 1 12

1

2 21 e v b

2 2 22

(5)

In (5), the diagonal elements give the share of domestic value added in a country’s gross export

(“trade in value added”) while the off-diagonal ones give the share of foreign value added in a country’s gross exports. These estimates can be used to compare trade imbalances in gross exports

in gross trade on the horizontal axis vs. in value-added trade on the vertical one. Each point is a trading partner of the U.S.. China lies below the 45-degree line, meaning that the U.S. deficit with

China is higher in gross trade vs. in value-added trade, which is natural in view of Figure 13. For

Japan, it is the other way around, which is also natural in view of Figure 13.

Figure 14: World trade imbalances, gross and in value added

1 With several sectors, each element of B would be a sub-matrix whose dimension would be the number of sectors in each country.

10

45 o line

Source : Koopman et al. 2011

The implications are very important in terms of “trade diplomacy”. Creating trade and hence political friction with China on the basis of its huge surplus in gross trade may not be a good idea if the gross trade figures reflect value added realized in other countries—in particular Japan—rather than China itself. Whatever China does with its exchange rate, if one looks at the ipod’s value chain, it is unlikely to make much of a difference on the value of an ipod and even less on employment in the U.S..

3 Is globalization irreversible ?

Globalization is often considered to be both new and irreversible. However, today’s globalization wave is the second episode, the first one having ended badly.

3.1 A first episode in the XIX

th

century

The development of railway and the first communication technologies (telegraph) in the XIXth century led to a first wave of globalization between 1815 and 1875, which was « officaliaized » by a web of bilateral free-trade agreements between the main trading nations in the 1860s. This wave of globalization was followed by a severe return of protectionism between 1875 and the First World

Was (

Cette vague de mondialisation a été suivie d’un retour du protectionnisme entre 1875 et la Première

11

Table 3: Average level of import tariffs, 1875-1913

Source : Bairoch et Kozul-Wright (1996)

While not able to stiffle the growth of international trade which was fueled by a massive decrease in transportation costs, the return of protectionism was accompanied by a rise in xenophobic and nationalistic rhetoric that contributed, together with trade rivalries (e.g. between the UK and

Germany) to the start of the First World Was. It is between the two World Wars that the antiglobalization movement reached its paroxysm, in particular between the Great Depression of 1929-

Figure 15: The de-globalization backfire

12

Source : WTO, World Trade Report 2013

Could such a collapse of globalization happen again? One might think so in view of the rise of xenophobic, anti-immigrant and cross-community hate speeches in all countries of the world and the dark political forces that surf on the wave. However there is one basic difference between today’s globalization wave and the previous one—the existence of supra-national institutions such as the World Trade Organization, the World Bank and the IMF that were created at Bretton Woods precisely to avoid a repetition of the tragedy of the 1930s. In particular, the WTO codifies what is allowed and not allowed in trade policy. We will return to this later on.

3.2 Convergence of cultural values?

A couple of years ago there was a debate about whether capitalism and democracy were universal or Western values. While people like Amartya Sen argued that democracy was a fundamental right and that economic freedom was closely linked with it, prominent statesmen in the East such as Lee

Kwan Yu of Singapore countered that democracy was neither necessary nor sufficient for economic development and was essentially a Western value. Are political values converging or not? And how about deeper cultural values?

The definition of differences in cultural values between countries goes back to the work of Hofstede

(1980) who characterized societies along five dimensions of work attitude from a worldwide survey of 117’000 employes of IBM (where he had founded a personnel research department) between

1967 and 1973. In their original form, the dimensions were (with some renaming to make them more transparent):

1.

Power acceptance

2.

Individualism

3.

Risk-aversion

4.

Competitiveness (what he called « masculinity »)

To which he added two others later on

5.

Patience

6.

Restraint

Hofstede’s work started an industry of cultural distance measurement and its implications for corporate behaviour (e.g. entry modes). Roughly, power acceptance is stronger in emerging countries ; individualism is strongest in Western industrial countries. Risk aversion is stronger in

Latin America and German-speaking countries. Competitiveness is very low, for instance, in

Scandinavia and in Chile as well, but very strong in Japan and Switzerland. Patience is strongest in

Asia; restraint is strongest in East Asia. All in all, what these traits tell us about societies is not always very clear.

Among questions that arise, one may wonder whether the country is the right unit of aggregation, i.e. whether intra-country variation is lower than between-country. If it is not the case, crosscountry comparisons would have little meaning.

13

Power acceptance

Figure 16: Hofsteded’s cultural categories in the world

Individualism

Source : http://www.clearlycultural.com/geert-hofstede-cultural-dimensions/uncertainty-avoidance-index/

Competitiveness (masculinity) Risk aversion

Source : http://www.clearlycultural.com/geert-hofstede-cultural-dimensions/uncertainty-avoidance-index/

More recently, Thoenig et al. (2009) measure cultural distance between countries i and j by a fragmentation index F ij

based on differences in individual responses to World Values Survey questions.

In order to understand what the index does, suppose that there is only one binary (yes/no) question.

Let i be a country and s i

the proportion of « yes » respondents. The internal fragmentation index is

F i

i s i

2

H i

(6) where H i

is the well-known Herfindahl index of concentration. The fragmentation index is equal to the probability that two individuals chosen at random in country i respond differently to the

14

(single) question considered.

2

The index of cultural distance between countries i and j is similarly defined by

D ij

1 s s i j

1 s i

1

s j

(7)

It corresponds that two individuals chosen at random in the countries i and j respectively answer differently to the same question. Still with only one question, but with multiple choices ( n = 1,…, N possible answers), the index becomes

D ij

n s s in jn

(8)

Finally, with k mutliple-choice questions instead of just one, one just takes the average of the question-specific index

D ij

1

K

k

1

n s s in jn

(9)

Tableau 1: Typical question of the World Values Survey

2 If s i

was an ethno-linguistic group instead of a group of similar respondents, F i

would be the index of ethno-linguistic fragmentation widely used by sociologists.

15

Source: World Values Survey

Figure 17: Evolution of cultural distance, 1989-93 to 2000-2003

Source : Thoenig, Maystre, Olivier, Verdier 2009

The existence of a substantial proportion of of points below the 45-degree line suggests that the cultural distance has gone down at least for a number of country pairs during the second wave of globalization (the current one). Moreover, Thoenig et al. show that international trade has been instrumental in this decrease. Empirically, the bilateral index value depends on the following observables:

Table 4: Déterminants of cultural distance

16

Source : Thoenig, Maystre, Olivier, Verdier 2009

17

Références

Bairoch, Paul, and Richard Kozul-Wright (1996), “Globalization Myths: Some Historical

Reflections On Integration, Industrialization And Growth In The World Economy”; WIDER discussion paper 113; Geneva: United Nations.

Johnson, Robert, and G. Nogueira (2010), Accounting for Intermediates: Production Sharing and

Trade in Value Added; mimeo.

Koopman, Robert; W. Powers, Z. Wang, and S.-J. Wei (2011), “Give Credit Where Credit is Due:

Tracing Value Added in Global Production Chains; NBER Working Paper 16426, Boston, MA:

National Bureau of Economic Research.

Hofstede, Geert (1980),

Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values

;

Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Thoenig, Mathias, N. Maystre, J. Olivier et T. Verdier (2009), « Product-Based Cultural Change : Is the Village Global ? » ; CEPR dp 7438.

WTO (2013), World Trade Report 2013; Geneva: WTO.

Yoshino, Yutaka (2012), Uncovering Drivers for Growth and Diversification of Tanzania’s Exports and Exporters; A Technical Background Report on Export for the 2014 World Bank Tanzania

Country Economic Memorandum ; Washington, DC: The World Bank.

18