Portland State University Angela Wilson & Christina Gildersleeve

advertisement

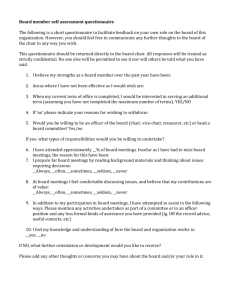

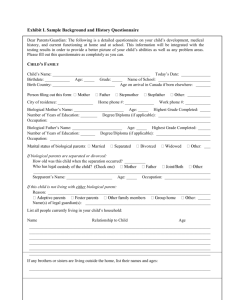

Clinician Instructions j Portland State University Angela Wilson & Christina Gildersleeve-Neumann Who should use this Questionnaire? This questionnaire has been designed for children between the ages of three and five years old who have speech sound disorders. The categories and questions included in this questionnaire were created based on word lists1, 3, 6, 7 and word selection tools2 for children in this age range. The questionnaire can be used with clinicians and families who want to create a treatment approach that incorporates functional speech targets. How should this Questionnaire be used? Instruct parents to read through each question and provide answers to the ones that are relevant to their child. The last page is available for parents to write down any words and/or phrases that they did not previously include. To get a full description of a child’s language, each section of the questionnaire should be considered. However, the questionnaire is long and can be timeconsuming for parents. You can describe each section to parents and check off (on the first page) the sections that you think are most important for a particular child. Also included on the first page is a place for you to circle the number of words that you would like parents to mark as the most meaningful to their particular child. Consider administering the questionnaire every 3 months to collect new words as communication develops. Why should this Questionnaire be used? Use this questionnaire to gather information to directly assist you, and families, in the selection of treatment targets and goals for children with speech sound disorders. The questions aim to determine which words a child currently uses, which words are meaningful, and which words are appropriate next targets for the child. The answers will aid in the process of determining words and phrases to use in therapy, which will create a treatment approach that is functional, meaningful, and motivating to children. This questionnaire offers a valuable opportunity for parents and clinicians to work together. Both clinicians and parents have reported that parental involvement is an essential component of intervention4, 8. However, a family-centered model of therapy is not always applied, and parents may feel left out of the process8. Parents have a great amount of knowledge on the impact of their child’s speech sound disorder and on their child’s language use. How should the Results be used in Treatment? Incorporate the words that parents provided to create a functional and meaningful treatment approach. Here are some suggestions: Modified Targets: Some children who have significant speech sound disorders may have the goal of producing modified and consistent target words. An example of a modified target for the word “bath” may be “bat.” Your assessment of a child’s speech sound inventory can help in the creation of modified target words and phrases. Typically you will model the correct production while also accepting the child’s modified version. Carrier Phrases: To increase utterance length and encourage generalization, have the child produce the words in carrier phrases. For example, if the word “water” is a target, it could be taught in the phrase “I want water.” There are many core vocabulary words that may not be elicited in the questionnaire, but are helpful to teach in phrases. Following is a list of some core vocabulary words that were consistently found in preschool age word lists1, 3, 6, 7 and word selection tools2: I You No Yes The Is Want It A And Can That Mine Me I’m My On In Go What There Have Has More Help Do Done Off Modifiers: As a child’s communication develops, add modifiers to the words and phrases they are learning. For example, when a child asks for a book, they can say, “I want the big book” or “I want the blue book.” How to Include Parents: Include the parents in the discussion of and creation of modified targets and carrier phrases. Parents should understand what these terms mean and why they are being incorporated into their child’s treatment. Invite parents to participate in treatment sessions and support them as they do so. This will help carryover the treatment goals to the home environment. Brainstorm with parents some home routines or activities that allow for use of the new words in functional environments. Also consider ways for them to practice multiple productions of targets to support their child’s goals. References 1. Banajee, M., Dicarlo, C., & Stricklin, S. B. (2003). Core vocabulary determination in toddlers. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 19(2), 67-73. 2. Fallon, K. A., Light, J. C., & Paige, T. K. (2001). Enhancing vocabulary selection for preschoolers who require augmentative and alternative communication (AAC). American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 10, 8194. 3. Marvin, C. A., Beukelman, D. R., & Bileu, D. (1994). Vocabulary-use patterns in preschool children: Effects of context and time sampling. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 10, 224-236. 4. McCormack, J., Mcleod, S., Harrison, L. J., & McAllister, L. (2010). The impact of speech impairment in early childhood: Investigating parents’ and speech language pathologists’ perspectives using the ICF-CY. Journal of Communication Disorders, 43, 378-396. 5. McIntosh, B. & Dodd, B. (2008). Evaluation of Core Vocabulary intervention for treatment of inconsistent phonological disorder: Three treatment case studies. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 25(1), 9-30. 6. Morrow, D. R., Mirenda, P., Beukelman, D. R., and Yorkston, K. M. (1993). Vocabulary selection for augmentative and alternative communication systems: A comparison of three techniques. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 2, 19-30. 7. Trembath, D., Baladin, S., & Togher, L. (2007). Vocabulary selection for Australian children who use augmentative and alternative communication. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 32(4), 291-301. 8. Watts Pappas, N., McLeod, S., McAllister, L., & McKinnon, D. H. (2008). Parental involvement in speech intervention: A national survey. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics, 22(4-5), 335-344.