Trading Kingdoms of West Africa: Background Information Originally

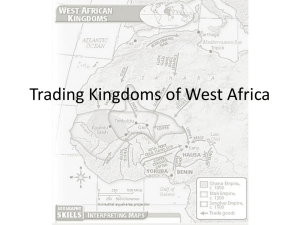

Trading Kingdoms of West Africa: Background Information

Originally Mali was a small kingdom located at the upper course of the Niger river, upstream from Bamako in a gold-producing area. Mali was formed between 1230 and 1240 A.C., when the Malinké (also called Mandingo), led by their warrior king Sundiata Kita con-quered many neighboring cities and lands. In 1235 Sundiata Kita de-feated the Sosso king Sumanguru and the old capital Kumbi Saleh was pillaged.

Sundiata moved his capital to Niani, the city of his birth. Niani was located on the borders of the Niger. Other important cities of Mali were Timbuktu, Djennée en Oualata; trade centres who played an important role in the caravan trade through the Sahara desert.

The Mali empire resembled a confederation of several different na-tions, ruled by a king, the

'mansa' of Mali. The kingdom, three times the size of the old Ghana empire, stretched from the

Atlantic ocean in present day Senegal/Gambia past the great bend in the Ni-ger river, east of

Gao.

Sundiata and some of the later kings of Mali, like Mansa Musa, were extremely efficient rulers.

The central part of the empire was divided into provinces, each with a governor of 'ferba'.

Major towns were administered by a 'mochrif' of mayor. Outside regions were autono-mously ruled by vassals, who paid allegiance to the King. The King ruled from the central capital Niani.

A huge army kept peace and policed the trade routes, the eastwest trade route als well as the provitable caravan routes from the salt mines in Taghaza in the North to the gold mines of

Wangara in the South.

Mali reached its Golden Age with the rule of Mansa Musa (1307 till 1332). Musa means

'Mozes'. Mansa Musa is therefore often called by historians 'the black Mozes'. Mansa Musa's brother, Abubakar, is said to have equipped an armada of several hundred ships. He set off across the Atlantic in search of land.

The Arabic traveler and scholar Ibn Battuta visited the capital of an-cient Mali between 1352 and 1354. He wrote down his experiences in his book Travels of Ibn Battuta.

'There is complete security in their country. Neither traveler nor inhabitant in it has anything to fear from robbers or men of vio-lence.'

The Egyptian historian Al Omari visited the court of Mansa Musa in 1325 A.C.

'Mansa Musa holds court in his palace on a great balcony called a 'bembe', where he has a great seat of ebony that is like a throne ... On either side it is flanked by elephant tusks. His arms stand near him, being all of gold - saber, lance, quiver, bow and arrows. He wears wide trousers made of about twenty pieces of material which he alone may wear. Behind him there stand a score or so of Turkish pages bought for him in Cairo. One of them, at his left, holds a silk umbrella ...'

Mans Musa organized a massive pilgrimage to Mecca in 1324. Inclu-ded in his large entourage were hundreds of servants, thousands of soldiers, and eighty camels bearing twenty four thousand pounds of gold. Most of which he gave away to strangers in Mecca and Medi-na. In

Cairo he gave every officer of the court a large amount of gold, causing acute inflation in the

Cairo market. It took twelve years before the gold markt recovered.

Mansa Musa's successors were not capable to hold the large empire together. The Tuaregs from the desert raided Timbuktu and the nor-thern cities Walata and Arawan. Tribes from the south attacked tra-ding caravans and military garrisons. Small ancient kingdoms saw their chance for independance. The once powerful Mali empire limped on for another twohundred years, but the days of prosperity and glory were over. In 1469 came the final end to the rule of the Malinké over western Sahel.

The Empire of Mali, the empire of the Mandinka

Period

Mali formed in about 1235, when warrior, Sundiata defeated the Sosso king Sumanguru at

Kirina and sacked the ancient Ghanese capital, Kumbi Saleh. The empire reached its Golden

Age with the rule Mansa Musa, King Moses, (1307 - 1332) till about 1469, when Sonni Ali of the Songhai leveled Timbuktu and the Mali capital Niani.

Government

Sundiata and some of the later kings of Ghana, like Mansa Musa, were extremely efficient rulers. The central part of the empire was divided into provinces, each with a governor of

'ferba'. Major towns were administrated by a 'mochrif', or major. Outside regions were autonomously ruled by vassals, who paid allegiance to the King. The king ruled from the central capital 'Niani'.

A huge army kept peace and policed the trade routes. "There is complete security in their country. Neither traveler nor inhabitant in it has anything to fear from robbers or men of violence." Ibn Battuta: Travels of Ibn Battuta. 1352 - 54.

Wealth flowed from the east - west and north - south trade, from the salt mines of Taghaza in the north and from the gold mines of Wangara in the south. "Square in shape, being four months in travel in length and at least as much as in breath..." Al Omari, Egyptian historian

1325.

Mansa Musa's brother, Abubakar, is said to have equipped an armada of several hundred ships. He set off twice across the Atlantic in search of land.

Capital

During the Golden Age of Mali Mansa Musa ruled from the capital Niani.

"Mansa Musa holds court in his palace on a great balcony called a 'bembe' where he has a great seat of ebony that is like a throne... On either side it is flanked by elephant tusks. His arms stand near him, being all of gold: saber, lance, quiver, bow and arrows. He wears wide trousers made of about twenty pieces of material which he alone may wear. Behind him there stand a score or so of Turkish pages bought for him in Cairo. One of them, at his left, holds a silk umbrella..."

Al Omari, Egyptian historian, 1325.

The Glorious Hajji of Mansa Musa

Mansa Musa organized a massive pilgrimage to Mecca in 1324. Included in his large entourage were hundreds of servants, thousands of soldiers, and eighty camels of bearing twenty four thousand pounds of gold (most of which he gave away to strangers causing acute inflation in the Cairo market. It took 12 years before the gold market recovered.)

Decline and fall of the empire

Devastating droughts, feuding amongst vassals and the invasion of the Songhay caused the decline and fall of the empire. In 1469 Sonni Ali, a Songhay warrior of Gao, leveled Timbuktu and Niani thus precluding the end of the Mali empire.

Present day Mali

Series of fatal droughts and femine during the seventies made wes-tern Sahel the topic of world news. Images of starving children and the dried-up earth appeared almost daily on TV and in the news-papers.

But Mali is much more than only a poor, dry country in the Sahel. Mali is the land at the upper course of the Niger River, where in the Middle Ages great empires rose to power with a superior clture. Western visitors find Mali one of the most authentic countries of Af-rica, meaning the way the people of Mali their clothing, their beha-vior and their material culture

(especially its architecture) main-tained its clear identity.

The former French colony was part of a federation with Senegal, that gained its independance on June, 26 in 1960. This federation fell apart less than three months later. On September, 22 in 1960 Mali became an independant nation.

The rule of Mali's first president Modibo Keita ended when, as a re-sult of foreign loans to finance great, unremunerative projects, no currency was left to import food for the starving people on account of a drought. The army overthrew the president and seized control. After

November, 19 in 1968 a military junta governed the country.

Moussa Traoré, leader of the military forces, gave the country a new constitution and Mali into a country which allowed only one politi-cal party. In practice this party was only interested in the wellbeing of Traoré and those who surrounded him. The government failed to carry out the necessary economic changes and became more and more corrupt. Mali depended completely on international aid. At the end of the eighties Traoré was forced by the donor countries to carry out important economic changes.

Dissatisfaction over the Traoré government grew more and more. In January 1991 a student revolt was struck down by killing 106 peo-ple. But two months later the military - joining the students - seized control and ended the Traoré government was overthrown. A tem-porary government and a National Conference were formed to write a new constitution. June, 8 in

1992 the first democratic chosen government under leadership of president Alpha Oumar

Konaré was installed.

He started a thorough reform of social en political institutions. Al-though the battle against corruption and illicit management is long from over and the country still depends largely on foreign aid, the developments give rise to great faith in the future of Mali.

The Kingdom of Songhay.

In that year the Songhay king Sunni Ali Ber conquered Timbuktu and killed thousands of its inhabitants. The capital Niani was des-troyed. After a siege of of seven years, seven months and seven days, the great city of Djennée (320 miles southwest of Timbuktu) surrendered to

Sunni Ali Ber, with all its riches.

In the north Ali conquered Walata, to the east the copper mines at Tadekka and annihilated the neighboring Fulbe people. Soon the en-tire former Mali empire came under control of Sunni Ali

Ber, King Ali the Great.

Gao became the commercial centre of the Songhay kingdom. The city was divided into two sections; one for the Muslim traders and one for the local Songhay people.

'Here at Gao are exceeding rich mercants; and hither continually resort great store of Negroes which buy cloth here brought out of Barbary [North Africa] and Europe. Here ... a young slave

of fif-teen years age is sold for six ducats, and so are children sold also ... Horses bought in

Europe for ten ducats are sold again for forty or fifty ducats apiece. A sword is here valued at three or four crowns and so likewise are spurs, bridles, ... and spices also are sold at a high rate; but of all other commodities salt is most extre-mely dear.' according to the Moorish historian Leo Africanus in 1510.

The Songhay were more influenced by the Arabic-I slamic culture as the southern Malinké and therefore probably better equipped to maintain trade connections with Muslim mercants. The

Songhay empire reached its culminating-point around 1500 A.C. during the Askia-dynasty.

Ali the Great's son became king after his death in 1492. The young king was overthrown a year later, and Askia Mohammed Touré or Askia the Great became the new and first ruler of the

Askia dynasty. Mohammed Touré was a devout Muslim and, like Mansa Musa, he undertook a spectacular pilgrimage to Mecca, accompanied by thou-sands of slaves and soldiers.

When he returned, he set about expanding the empire through a se-ries of holy wars, of jihads.

Within a year the Songhay empire was three times larger than Mali had been and occupied almost the entire western Sudan.

The Songhay empire was divided into five provinces, each with its own governor. There was a central government of ministers respon-sible for various departments, including the treasury, the navy (the Songhay canoe fleet), tax collection, the forests, the woodcutters and the fishermen. Every town and village had a mayor appointed by the King. Islamic judges were appointed to every large district. The King's court was the highest court of appeal.

Mohammed Touré created a professional fighting force. His soldiers were well trained and equipped and housed in military camps and were ready to move at a moment's notice.

The successful trade with North Africa not only brought great wealth, but in the end also led to the destruction of the Songhay em-pire. The greedy and already extremely wealthy sultan of

Morocco believed that if he could control the salt and gold sources, he could become even richer.

The Songhay army, equipped with swords, spears and arrows, were no match against the gunfire of the sultan's army. In 1585 they con-quered the salt mines of Taghaza and in 1591

Timbuktu and Gao fell. The 150 year old kingdom of the Songhay seized to exist.

'Judar Pasha (leader of the Moroccoan army) returned to Morocco laden with treasure for the greedy sultan. He had thirty camels loa-ded with gold dust, a great store of valuable pepper, one hundred and twenty camel loads, of special wood and horns used by the Mo-roccan textile and leather dyers. There were fifty horses and great numbers of slaves, as well as fifteen of the king's daughters of Gao, which were to be the Sultan's concubines.' so told by Jasper

Thomson a few years later in Marrakech, Morocco.

Because the Sultan's army could not find the secret sources of gold they gave up Songhay as a lost cause. Important trade centres like Timbuktu and Gao on the other hand remained for almost two cen-turies under the rule of the sultans of Morocco. The Songhay empire was scattered. Moorish soldiers who occupied the Songhay cities be-gan a reign of terror that endured well into the eighteenth century.

'Security gave place to danger, wealth to poverty; distress and ca-lamities and violence succeeded tranquility. Everywhere men des-troyed each other. In every place and in every direction there was plundering, and war spared neither life nor property nor persons.' described

El Sadi in 1656 the sad situation in the old Songhay em-pire. The vast savannah of western

Sudan became home to thousands of refugees, fleeing both the slave raids and warring armies of rival states, a chaos that never ended.

Ships replace camels.

For centuries, Europeans heard only vague rumors about Ghana, Mali and Songhay, kingdoms, kingdoms of gold. Arab travelers told tales of 'the richest king of the world', thriving market cities, and huge armies of well equipped soldiers. Exactly where these king-doms were located, they could not say.

In 1441 'Enrique the Explorer' of Portugal sent his mercant explorer ships to find the famed gold at the Guinee coast (Gold Coast). Here they encountered Africans nog only willing to trade gold, but also black slaves.

Black slaves were used for centuries at the Iberian penninsula. They were mostly owned by important and wealthy Arabs, who had con-quered large parts of the penninsula during the eighth century. Enri-que the Explorer knew the value of black slaves.

Along the coast trade posts were established. More and more the long-distance trade moved to the coast. The Atlantic navigation en-abled the Europeans to cut out many of the intermediaries connected with caravan trade. The caravan trade through western Sudan was re-duced more and more. The trade routes now longer were safe due to nomads. like the

Touaregs, attacking caravans. This ended western Sudans most omportant source of income; trade.

By the time European nineteenth century explorers reached the in-lands of western Sudan, the old trade cities of Ghana, Mali and Songhay had disappeared or were in decline.

By the late nineteenth century European countries no longer were sa-tisfied with only trading posts along the coast. Large parts of Afri-ca's inland was colonized. The borders of these colonies were drawn rather randomly at the drawing board, because of which the living area of some etnic groups were spread along two or three colonies. The territory of the once glorious

Songhay kingdom is now divided between Mali, Burkina Faso, Mauritania and Guinea,

Senegal and Nigeria. http://www.kurahulanda.com/west-african-kingdoms/west-african