Plato`s Craft Analogy

advertisement

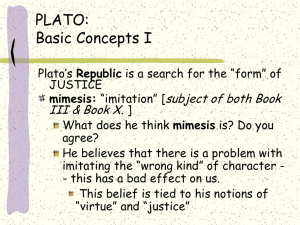

Plato’s Craft Analogy – Competing Conceptions of Knowledge Charlotte Dab Shi Chen 2 Charlotte Dab Charlotte Dab Shi Chen Political Views December 5th 2012 Plato’s Craft Analogy – Transcending Knowledge After more than 200 years, Plato is still regarded as a major figure in the development of political theory. One of his most lasting political ideas is the argument against democracy in The Republic. He rejects the rule of the rabble and advocates a concept of government run by philosopher kings. In order to defend that notion, he resorts to one of his most famous analogies, that of the craft. There are valuable insights to be gained by looking at the craft analogy, examining counter arguments, and finding a sound defense of Plato’s position. Plato’s rejection of democracy is based in part on the trial of Socrates and its manifestation of mob rule. Against it, he proposes the alternative of a perfect republic: “which is his detailed blue print for a harmonious and thus perfect society ruled over by wise philosopher-rulers” (Robinson, 21). Plato defends his ideal state and undermines the foundation of democracy by using the famous craft analogy. The craft represents a concrete notion of expertise. To have good government only a trained expert can run the state in the same way that only a trained captain can navigate a ship and not the untrained sailors. Plato affirms that the inexperienced sailors all would want the captain’s position, and may even go as far as killing him. In so doing, the sailors would disregard the fact that there are a great many skills required for the craft of being a captain. Once the captain is gone, the sailors will praise and worship he who is the more popular and charismatic of the seamen Charlotte Dab 3 without paying much attention to his degree of knowledge of the craft. The sailors, as a crowd, give much more value to the superficial qualities of their leader than to his level of competency. It is the same in politics. Citizens left to their own device will vote in the same way as the sailors; casting their votes based mainly on candidates’ popularity, charisma and social aspects. The general public will always disregard the better-qualified candidate. By “letting the people vote was like letting the passengers steer a ship – far better to let people who knew what they were doing take charge” (Warburton, 6). Plato believes that choosing leaders on such premises can only create disaster to society. His ideal of an effective ruler is the so-called philosopher-king. They are chosen by experts and follow a rigorous training for the purpose of being fair and effective leaders working for the greater good. The specialized education that they will receive provides the philosopher king with a great knowledge of the craft of government. Plato assumes that the philosopherkings will better serve the interest of the general public. Even though the craft analogy appears convincing and logical, it’s application to politics raises certain questions. The analogy rests on the concept of expert knowledge. Obviously, such knowledge has to be passed on from generation to generation. Since philosopher-kings will be the ones overseeing the training of their successors, it would appear that standardized values are passed on. If this is the case how will governance of The Republic come to reflect the changing circumstances of history? How would progress be integrated in good government? Also, knowledge and experience don’t always develop at an early stage in life. The determination of the future philosopher-kings could be impeded by wrongful pre-mature Charlotte Dab 4 selections. Not everyone develops at the same rate. Some of the greatest minds were late bloomers. In the end, knowledge is relative, “Nietzche thought that what counted, as knowledge was simply that which the strongest imposed on everyone else.” (Robinson, 157) In the light of what precedes, it is obvious that however imperfect, democracy has just a good of chance to choose a good philosopher king as the method of selection of Plato The counter argument about the craft analogy is in part a critique of the acquisition of knowledge in the development of the philosopher kings. It is based on a conception of the need to have leaders who have had the opportunity to acquire knowledge through life experience before being appointed/elected. This is limitative in that it does not take into account that the early selection of candidates to become philosopher king must be seen in a psychological context. It must be assumed that they are selected even at a young age on criteria of personality and temperament where it is apparent they be the type of person who will seek better knowledge later in their career from experience. We learn from Shakespeare that character is destiny. In Philosophy for Dummies, “there is a fear that sharing knowledge is like sharing a piece of pie” (Morris, 103). Information is not like a piece of pie. Knowledge multiplies as it is shared and added to people’s experience. If the best are selected from the beginning and taught what their professors were taught, they will understand and integrate the lessons of experience and history including new innovations. The elite are chosen for their innate quality of soul and character, which guarantees a certain aptitude to acquire true knowledge and use it for the greater good. According to Plato, there are three types of souls: the guardian, the auxiliary and the Charlotte Dab 5 merchant. The guardian, also known as the philosopher-king, is the most rational one and should be the leader. Plato believes that in his an ideal society, all three souls should play a role. However, only the guardians should make decisions because only they carry the capacity to gain and spread knowledge. Plato’s understanding of human beings is that they are innate with certain skills; therefore, philosopher kings are chosen by their souls and not by any other means of test. If we believe the concept of innatism, which is that “we are all born programmed with certain kinds of knowledge” (Robinson, 22) Essentially, not everybody is the same and not everybody has the same capacity to acquire knowledge. When the right to vote becomes a freedom for every citizen, disasters will arise. If the German population had had the requisite knowledge and awareness, as would a trained philosopher-kings, then Hitler would perhaps not have come into power. Another point about knowledge is that sometimes it brings about great deception. Plato explains this theory in great detail with his famous cave analogy. The shapes and forms that were being displayed amused the prisoners who remained in the cave. One of the prisoners was freed and saw that the shapes and forms were just shadows. He had the knowledge and shared it with his friends who were in the cave. His friends chose to not believe him, as it would ruin their entertainment. This proves that not everyone is ready to accept real knowledge as it can sometimes be damaging. If those who aren’t mature enough to welcome absolute knowledge, then should they be in the position to vote? In other words, if you don’t have all the facts, you simply can't make a sound decision. Banning art from the general population is perhaps a strong stance; nonetheless, it does have valid reasoning. Plato believes that art creates disillusionment. It should be disapproved as it leads to lies. Charlotte Dab 6 The evolution of Western democracy in our time would please Plato. Yes we do elect representatives bodies to our governments and they represent the interest of those who elect them. Their influence is limited to make laws, not to apply it and they usually serve for a limited term. The reality of power rest in the civil servants who run the country with great-acquired skill and fairness to all. They are an elite that has been highly trained and mentored in the best elite schools to exercise power, they are lifers and they have no major wealth, almost the major traits of Plato's ideal ruler. 7 Charlotte Dab Works Cited Morris, Tom. Philosophy for Dummies. New York: Wiley Publishing Inc. 1999. Print. Robinson, Dave and Groves, Judy. Introducing Philosophy A Graphic Guide to the History of Thinking. Cambridge: Icon Book Ltd., 2007. Print. Warburton, Nigel. A Little History of Philosophy. U.S.A., Yale University Press, 2011. Print.