View/Open - Cadair - Aberystwyth University

advertisement

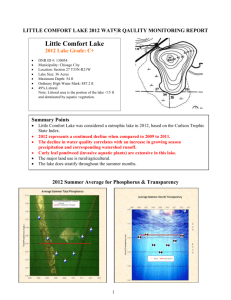

Repositioning The Shire Valley Project – a retrospective (Part I) – Governing nature Marc Welsh Aberystwyth University The Shire Valley Project (SVP) was an integrated macro-development programme that aimed: to regulate the level of Lake Malawi, to capture the hydro-electric potential of the Shire River and to open up and irrigate a vast tract of the Lower Shire Valley. It has had an enormous impact upon the landscape, livelihoods, people and economy of Malawi. Yet its significance in Malawi’s own formation and its origins as a response to the problems of an unruly natural world have perhaps been underappreciated and certainly under researched. In this paper I explore how a state rationale for regulating nature, in the form of the SVP, emerged in the 1940s as an ongoing response to a dynamic hydrological system. In a subsequent paper I develop this argument further and point to the importance of the Liwonde barrage and Nkula Falls schemes in the geopolitical levering of the Nyasaland Protectorate out of Federation. The main purpose of this paper is to suggest a reconsideration of the Shire Valley Project (SVP) as a centre-piece of colonial and post-colonial government planning for the development of Nyasaland/Malawi. Implemented piecemeal the SVP was partially successful in achieving sometimes incompatible objectives yet the governmental rationale of seeking to regulate the hydrology of Malawi to make waters and land productive in a globalising economic system persists to the modern period. The Shire Valley Project The Shire Valley Project originated as a major integrated development scheme of the colonial government of Nyasaland Protectorate during the 1940s. The developmental and plan led discourse of post-War British colonial government, driven by a circulating network of experts and expert knowledge, combined twin objectives of regulating the lake level with the control of waters flowing through the Shire Valley. Conceived in terms of a hydrological system in dynamic equilibrium seasonal waters flowing into the Lake would be released in a timely manner to allow permanent and controllable release into the Shire River throughout the year. This would allow stabilisation of the lake, expansion of water transport, the generation of hydro-electricity, the establishment of a vast irrigation program in the Lower 1 Shire Valley, and the prevention of flooding. In short the Shire Valley Project would “revolutionise the economy of Nyasaland” (Governor Colby (1956: 279)). So where did the idea for such an ambitious undertaking come from? Malawi’s unruly waterways The Nyasaland Protectorate was founded on water. Its ‘discovery’ and exploration by European powers occurred through navigating the waterways of central Africa. Towns and estates were located near sources of freshwater, boundaries demarcated along water features, imperial land claims to territory staked and enforced through military force on the waters. Moral authority of the imperial project was legitimised through tackling slavery on the Lake, and fundamentally Nyasaland Protectorate was linked to the rest of the Empire though the Shire-Zambezi waterway. Yet the behaviour of the waterways has always been capricious rarely playing ball with the desires of government. The water balance of Lake Malawi is dominated by rainfall over the lake itself and evaporation. This in turn is heavily influenced by the Indian Ocean Dipole and the El Nino Southern Oscillation (Becker et al 2010). The Shire River is the only outflow, running southwards through the Shire Valley to join the Zambezi River in Mozambique. The balance between water flowing into Lake Malawi and leaving it again (mostly by evaporation from the lake surface) is delicate. A relatively small reduction in rainfall across the Lake’s catchment area, or a relatively small increase in evaporation, results in a progressive annual reduction in the volume of water in the lake (Drayton 1984). A drop in average levels of just a few metres would result in Lake Malawi becoming a ‘closed lake’, in other words no water would flow out of it. This happened in 1915, lasting for about twenty years and the perennial worry is it may happen again. Conversely an increase in precipitation results in a raising of the level of the lake, flooding lakeshore areas and resulting in an increase in the volume of water discharging down the Shire River. As the climate of the region has changed so has the level of Lake Malawi, and by quite large amounts with affects upon people and nature. Geological records suggest that 25,000 years ago the Lake surface may have stood nearly 300 metres lower than today (Scholz & Rozendahl 1988). The variation in Lake Malawi’s levels and in particular quite pronounced drops in its levels even seem to account for the high diversity of cichlid species in the lake (Owen et al 1990). So variation in the level of the lake is a feature of the hydrology of Malawi, as is variation in the level of the Shire River and its tributaries and its propensity to flooding and drying up (see Kumambala & Ervine 2010). 2 Navigating the waterways For the early colonial government even from its outset navigation on the Nyasaland waterways was seasonal and varied between years. For example in 1896 the Lower Shire river could be navigated by large steamer all the way up to Chikwawa (the ALCs ‘Katunga station’ see Bamford 2009, Welling 2009) for most of the year.1 Barely ten years later navigation beyond Port Herald/Nsanje was problematic. Similarly steamers plied the Upper Shire from Matope on to the lake (see Kanthack 1941, and Fredrick Moirs account of his time with the African Lakes Corporation in ‘After Livingstone’ (1923)). By 1905 navigation on much of the Upper Shire ceased as water levels dropped and vegetation growth made navigation impossible. Outflow from Lake Nyasa into Lake Malombe ceased in 1915 (Kanthack 1941). On the Lower Shire increasingly limited navigation above Port Herald fed into justifications for, and government investment in the extension of the railway north from Port Herald to Chiromo, and later (1913) south to Chindio. Insert figure 1 – Map of Shire River from 1890 At various times between 1910s and 30s the colonial government considered proposals for alleviating the problems of navigability and the possibility of generating power from the Shire River. For example, in 1904 the Oceana Consolidated Company, planning a major cotton estate investment on the Lower Shire, requested the Foreign Office take action to improve the navigation of the Shire.2 Identifying the build up of a “bar” at the outlet of the Lake as the principle cause of low water levels in the Lower Shire they urged the purchase and deployment of a dredger to mechanically re-engineer the upper part of the river. In 1922 the more fundamental alteration in the flow of the river was contemplated. The Nyasaland Chamber of Agriculture and Commerce suggested to the Governor turning the Upper Shire River into a “closed canal”,3 an idea the colonial administration reconsidered again in 1927 as concerns grew following a year on year rise in the level of the lake. The report concluded that such work was impractical 4 with a key contingency being uncertainty over the future height of the lake and its discharge into the Shire. 1 British Central Africa Gazette, November 1st 1896, page 3 CO 525/5 – Foreign Office, 1904, South East Africa Confidential No. 15 3 S1 1420/22 – Suggestions to turn the Upper Shire into a closed canal 4 CO-525-122-10 – Report into Reopening Navigation on the Upper Shire River, 1928 2 3 Figure 1: photograph of a ‘Map of Shire River Shewing extent of British Protectorate’, prepared 1890. Copy held National Archives, Kew 4 Around this time the ‘Government Geologist’, Dr. Frank Dixey, began to investigate and formulate hypothesis about the lake and its behaviour.5 Dixey published his findings in Nature in 1924. He concluded that like another great African lake, Lake Victoria, a cyclical correlation between lake levels and sunspot activity could be observed. Based on this he predicted lake level rise would peak in 1928. The lake did not comply. The level of the lake had begun to rise since the mid-1920’s. Dixey had a theory that it followed the 11 year solar cycle. This was readily revised when the Lake rose faster and sooner than anticipated and then continued to rise year on year. As a result the planned rail terminus and extension north to the lake shore at Domira Bay in 1934 had to be relocated to Salima and a rail/lake port interconnection created at Chipoka.6 Now this concern with the rise and fall of Lake Nyasa was not merely academic nor focused solely on the implications for commerce and navigation and building the railway. By the early 1930’s District and Provincial Commissioners were regularly writing reports highlighting effects of inundation upon lakeshore villages and their food resources.7 In 1933 the bars along the Upper Shire were finally overtopped and began to be washed away. Yet the lake continued to rise for another four years resulting in village resettlement around the lake shore. The overtopping and gradual erosion of material in the river had disastrous effects downstream. For example, a build up of ‘sudd’ (vegetation) behind the Liwonde bridge, followed by erosion of the river bed, damaged the bridge at Liwonde so severely it could no longer be used and a ferry service at Liwonde had to be instituted. Further downstream the Lower Shire was also rising, so much so that in 1935 consideration was given to re-establishing river transport on the Lower Shire from Chikwawa to Chiromo.8 It was around the time of this high water mark (1937), and around these themes of rising lake levels, flooding and transport that the idea of holding back the waters of Lake Nyasa came to be intimately associated with opening up large areas of land for farming in the Lower Shire valley. A rapid rise in Shire River levels in 1938-39 resulted in “vast areas on the Lower Shire”9 being flooded before food and commercial crops were harvested. At the same time on the Upper Shire flooding and the build up of sudd vegetation led to the Appointed in 1921 Dixey would prove a key figure not only in Nyasaland’s development (notably of its water supplies) but much more widely as a leading expert on hydrogeology, later Director of Colonial Geological Surveys and a key hydrologist for the UN (Dunham 1983) 6 CO 535/153/3 – Extension of railway to Lake, 1934 (item 26) 7 For example, see PCC 1-21-1 – Meteorology – Lake Levels 1931-62 8 A 3/2/220 – Department of Agriculture: River Transport – opening the Lower Shire for river transport, 1935-37. 9 Nyasaland Protectorate. 1938. Presidents Address, Summary of the Proceedings of the Legislative Council of Nyasaland, Fifty-Fourth Session, 13th and 14th September 1938, Government Printer, Zomba. 5 5 destruction of two piers on the new railway bridge at Mpimbi (south of Liwonde) severely hampering the ability of growers in the north (primarily of tobacco) to transport their goods south to the sea routes.10 The Unruly Lake This all came together in a crystallising of colonial opinions at this point in time (late 1930s). The unruly behaviour of Lake Nyasa was affecting settlement, destroying infrastructure, damaging commercial and domestic crop production, reducing the revenues of the territory, and not limited in affect to lakeshore areas. The lakes behaviour had in fact become a problem. The frustrations of the colonial government caused by ‘vagaries’ of Lake Nyasa are nicely summed up in this extract from the ‘Bell Report’ (1939) into the Further Development of Nyasaland: “With the rise of the Lake the River Shire has again begun to flow in the dry season. In 1936 the river and sudd swept away the bridge on the Zomba-Fort Johnston road and this year damaged the new railway bridge lower down so seriously that an entirely new bridge will be necessary to replace it. The vagaries of Lake Nyasa and the Shire River since Livingstone discovered the Lake are the most eccentric of the natural phenomena with which man has contended in Nyasaland” (ibid, pp 112, emphasis added) So what should be done about this unruly lake? Francis Edgar Kanthack, “imperial engineer” par excellence who oversaw the biggest dam projects in southern Africa and published widely on irrigation engineering methods (Beinart et al 2009) published a piece in the Geographical Journal in 1941 entitled “The Fluctuations of Lake Nyasa” (1941). This paper would form the baseline for many hydrological investigations of Malawi in years to come. He concluded that regulating the discharge of water into the Shire at between 4,000-8,000 cusecs would maintain the level of the lake at a stable height. In 1942 he sent a copy of his article to the Chief Secretary of the Nyasaland Protectorate. Although not covered in any detail here this flood period (known locally as ‘Bomani’) was highly significant in local histories of the Lower Shire. See Elias C. Mandala’s, ‘Work and Control in a Peasant Economy’ (1990) for a fascinating exegesis of immediate and longer term effects of this event. 10 6 By 1944 post-war planning in the UK and in its imperial “possessions” began in earnest. Juxon Barton (then Chief Secretary for the Nyasaland Protectorate) approached Kanthack on behalf of the Governor asking if he could advise on “the question of the stabilisation of the Lake level”.11 The rationale was that stabilisation of the lake be included in Nyasaland’s postwar development plans. The “Kanthack Report” (1945)12 was submitted in 1945. In it he plumped firmly for the building of a barrage at Liwonde (total cost about £155,000) where the Shire River cuts through a belt of gneiss. This barrage was expected to operate through nine 40 ft wide and 10 ft high sluice gates with the capacity to allow the unimpeded flow of water when necessary. While Kanthack was primarily concerned with stabilising the lake other interests were also planning ahead, thinking of the post-war investment by the Empire in the ‘Cinderella state’. For example, the Empire Cotton Growing Corporation (ECGC) ran experimental farms and educational programmes aimed at encouraging African garden farmers to establish cotton cash crops. Flooding and aridity in the Lower Shire valley made expanding cotton production or increasing land available for food production problematic. So representatives of the ECGC submitted ideas to the Nyasaland Agriculture Department ahead of Kanthacks visit. These proposals connected the dots between Kanthack’s proposition for stabilising outflow from the lake at one end of the Shire and the implications that such regulation could have upon agriculture in the Lower Shire. The ECGC assumption was that a barrage would be built at Liwonde as per Kanthacks 1941 article, with a second barrage at Matope to both make the Upper Shire navigable and to generate electricity. They also advocated building two long canals below the Murchison Cataracts on either bank of the Shire that would run off parallel to it. The eastern canal would run along the base of the Cholo escarpment and discharging into the Ruo River above Chiromo. The western bank canal would run down to near the border with Mozambique.13 Smaller barrages would be built on each tributary to the Shire, controlling water flow into the Shire during the rainy season to minimise flooding and feeding water into the canals for irrigation purposes in the dry season. S51/1/4/2 – Lake Nyasa 1944-47 – file item 1. Copy of report kept in CO/196/6 – Stabilisation of Lake Nyasa 13 Interestingly the idea of diverting waters from the Murchison (Kapichira) Falls for agricultural purposes has resurfaced a number of times since. For example the original plans for the Kasinthula Irrigation Demonstration Farm and Fish Farming Training Centre (just south of Chikwawa) in 1970 were based on this. This canal was not constructed and waters have to be pumped from the Shire River. 11 12 7 In this way the ECGC proposal envisaged that “virtually all the water reaching the Lower River area from north, east and west” would be controlled and used for irrigation. A memorandum submitted by the Senior Entomologist of the ECGC (Mr. E.O Pearson) in August 1944 titled “The control of the Shire River” 14 outlines the three elements of regulation needed in proposals for development of the Shire Valley: 1) “The stabilization of Lake levels, leading to a. The extension of navigation to Liwonde b. The stabilization of lake shore agricultural areas c. The development of permanent fishing beaches d. The security of bridges, roads and settlements 2) The provision of electric power from hydro-electric plant on the Middle Shire to be used in townships, factories, and industrial undertakings in the Shire Highlands 3) The control of the Lower River, leading to e. Reclamation of land at present flooded f. Irrigation of non-flooded land.” This combination of projects would form the centre of government and commercial thinking about the “development” of Nyasaland Protectorate for the next few decades in the form of the Shire Valley Project. Development and the SVP Immediately after its publication the Kanthack Report was forwarded to the Nyasaland Protectorate Post-War Development Committee and measures to take forward the lake stabilisation project were quickly accepted by and incorporated into the 10 year development plans for Nyasaland.15 The committee also recommended a survey be carried out with a view to reclaiming the flood lands in the Lower Shire river. Whilst the British Treasury were 14 S51/1/4/2 – Lake Nyasa 1944-47 – file item 18a 15 S51/1/4/2 – Lake Nyasa 1944-47 8 less generous than hoped for, allocating just £2.5 million of the £7.5 million sought to finance the Nyasaland Development Plan, the cost of the barrage was relatively low at an estimated £155,000. There is little doubt that progress building the Liwonde barrage would have been fairly rapid. Unfortunately the intervention of another expert (Professor Frank Debenham from Cambridge University) - who believed cyclical fluctuations in rainfall had little effect upon the level of the lake and a barrage at Liwonde would be a mistake – led to the UK Post-War Development Committee deleting the budget for actually building the barrage and instead inserting £5,000 for a further survey of the scheme. This survey (the ‘Griffin Report’, 1946) estimated costs of the integrated scheme at between £2.5 million and £3.25 million but owing to paucity of data recommended a further three year period of survey work. To get the work underway 15 new posts were created in the Nyasaland administration. Chief amongst these was the appointment of a Mr. Creaner in 1948 as Irrigation Engineer, the same year Governor Colby took up office. By 1949 Creaner had formed his own conclusions about the lake and its dynamics, and identified a barrage at Liwonde as the prime spot for regulating the level of Lake Nyasa and also flow down the Shire River for irrigation downstream.16 Newly in post Governor Colby submitted the recommendations to the Colonial Office. He had latched onto the significance of the Shire Valley Project for Nyasaland’s development and even sought to have them included on the agenda of the Zambezi Conference to ensure their rapid progression.17 Later outlining the rationale of his governorship Colby stated that “before we could contemplate any extension of social services [in Nyasaland] we had to create conditions favourable to the expansion of the revenue which would pay for these services.” (Colby 1956, page 274). Where the Nyasaland African Congress (NAC) emphasised investment in education, training and healthcare the priorities of Colonial Government were concerned with the practicalities of generating revenue to pay for it. So education and training should focus on farming techniques, soil management, producing crops of the right quality to command a good market price, rather than the skills needed for participating in the running of the economy. CO 525/212/5 – Lower Shire Survey 1949 - Report by the Irrigation Engineer, Mr Creaner, on measures required to stabilize water levels in Lake Nyasa, with a graph and table showing the degree of control required on water flowing into [sic] the lake from the Shire River. 17 This was a “confidential” meeting on August 29th 1949 of representatives of British territories governing the Zambezi. The purpose was to present development projects of the territories that might be on or near the Zambezi. 16 9 But in the SVP Colby had an early (and frustrating) opportunity to push the interests of his Protectorate to the top of the agenda creating those conditions for economic development rather than scraping for crumbs. As he described it in a speech given in 1956: “there is a scheme in hand to stabilise the level of the lake by building a barrage across the Shire River and the water will be able to be used to bring large areas of land under cultivation. This project will of course cost a great deal of money and will take many years to complete. I can say without fear of contradiction that its completion or even its initiation will revolutionise the economy of Nyasaland and will do an enormous lot to raise living standards and make further development possible.” (Colby 1956: 279) While Creaner had settled on Liwonde for the barrage (the essential first stage of the SVP) both Professor Debenham and Griffin disagreed with him (feeling the issue of silting up and growth of sudd would prove a major problem) and made their views known to the Colonial Office and Colby. As a direct consequence of the uncertainty raised by Debenham and Griffin’s intervention the CO was able to defer further decisions until a “more complete picture” was known. To work up proposals to a stage where formal financing from UK and international financial institutions could be obtained a further investigation (costing £300,000) was proposed to look at all aspects of the integrated SVP. This survey work was undertaken by a mixture of staff in Nyasaland but overseen and prepared by Sir William Halcrow and Partners. During the period of its preparation discussion of the logic and merits of the scheme circulated widely amongst the Nyasaland European elite, in the letters pages of the Nyasaland Times and including members of the Nyasaland Society (see for example Richards 1954).18 The ‘Halcrow Report’ was finally published, (complete with costings, detailed plans and phasing for different components of the SVP), in 1954 after Nyasaland’s federation with the Rhodesias. Embroiled within the fractious politics of the Federation the SVP would become one of a number of touchstones for the conflict between the different governments that sought to govern Nyasaland and its people. The unruly behaviour of Lake Nyasa would form a core component of this contestation and ultimately form a political key site of contestation in the unravelling of the Federation. 18 Richards was Chief Engineer for the SVP. 10 References: Agnew, S. 1973. ‘The Shire Valley Project, the Halcrow Report in Retrospect’, Seminar paper delivered to the University of Malawi, Chancellor College. Bamford, M. 2009. ‘The Search for Katunga - "Blantyre's Port"’, Society of Malawi Journal, 62 (1) 37-51 Becker, M., Lovel. W., Cazenavea, A., Güntner, A., Crétaux, J-F. 2010. ‘Recent hydrological behavior of the East African great lakes region inferred from GRACE, satellite altimetry and rainfall observations’ presented by Ghislain de Marsily, Comptes Rendus Geoscience, 342 (3) 223-233 Beinart, W. Brown, K. Gilfoyle, D. 2009. ‘Experts and Expertise in Colonial Africa Reconsidered: Science and the interpenetration of knowledge’, African Affairs, 108 (432) 413-433. Doi: 10.1093/afra/adp037 Bell, R. D. 1938. Report of the Commission Appointed to Enquire into the Financial Position and Further Development of Nyasaland, London, HMSO Colby, G. 1956. ‘Recent Development in Nyasaland’, African Affairs, 55 (221) 273-282 Dixey, F. 1924. ‘Lake Level in Relation to Rainfall and Sunspots’, Nature, 114, 659-661 Drayton, R. S. 1984. ‘Variations in the level of Lake Malawi’, Hydrological Sciences Journal, 29 (1) 1-12 Dunham, K. 1983, ‘Frank Dixey 1892-1992’, Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society, 29: 158-176 Griffin, A.E. 1946. A Report on Flood Control and Reclamation on the Lower Shire River and other Specified Areas in Nyasaland, published HM Crown Agents for Colonies, Millbank: London Kanthack, F. E. 1941. ‘The Fluctuations of Lake Nyasa’, The Geographical Journal, 98 (1) 20-33 Kanthack, F. E. 1945, Report on the Measures to be Taken to Permanently Stabilize the Water Level of Lake Nyasa, Government Printer: Zomba Kumambala, P., G. & Ervine, A. 2010 ‘Water Balance Model of Lake Malawi and its Sensitivity to Climate Change’, The Open Hydrology Journal, 4: 152-162 Mandala, E. C. 1990. Work and Control in a Peasant Economy, A history of the Lower Tchiri Valley in Malawi 1859-1960, University of Wisconsin Press: Madison 11 Moir, F. 1923. After Livingstone: Early days in Central Africa with the African Lakes Corporation, reprint by Rotary Club of Blantyre, Malawi with permission from Hodder & Stoughton, (1986) Owen, R. B., Crossley, R., Johnson, T. C., Tweddle, D., Kornfield, I., Davison, S. , Eccles, D. H., Engstrom, D. E. 1990. ‘Major Low Levels of Lake Malawi and their Implications for Speciation Rates in Cichlid Fishes’, Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Series B, Biological Sciences, 240 (1299) 519-553 Richards E. V. 1954. ‘The Shire Valley Project’, Society of Nyasaland Journal, 7 (1) 7-18 Scholz, C. A. & Rosendahl, B., R. 1988. ‘Low lake stands in Lakes Malawi and Tanganyika, delineated with multifold seismic data’, Science, 240 : 1645-1648 Sharpe, A. 1918. ‘The Backbone of Africa’, The Geographical Journal, 52 (3) 141-154 Welling, M. 2009. ‘Notes on the Presumed Location of the ALC Station at Katunga’, Society of Malawi Journal, 62 (1) 52-61 Wood, J. R. T. 1983. The Welensky papers, A history of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, Graham Publishing: Durban. 12